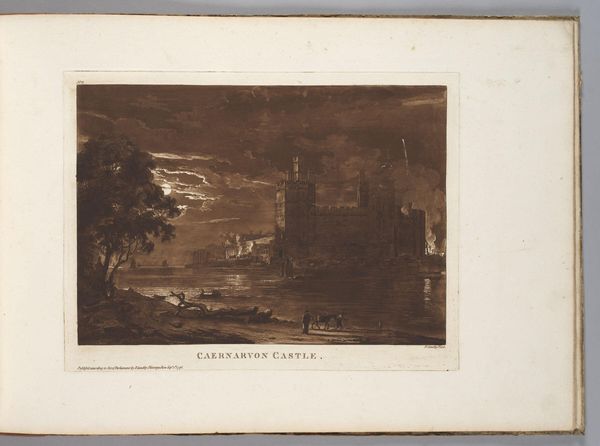

Dimensions: 239 × 315 mm (plate); 320 × 463 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Let’s explore Paul Sandby’s "Caernarvon Castle," made in 1776. It’s a print combining etching and watercolor on paper, held here at the Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: My immediate impression is one of somber grandeur. The monochrome palette creates a sense of historical weight, and that looming castle seems almost oppressive. Curator: Absolutely. Consider the date, 1776. What was happening then? Revolution! The depiction of Caernarvon Castle carries echoes of colonial power, both the imposition and the potential disintegration of it. Sandby's careful articulation of the architecture speaks volumes about identity. Editor: Indeed. Sandby was a master printmaker. This etching process allowed for incredible detail, emphasizing the texture of the stone and the water, but let's not overlook that the watercolor adds to the image, which brings us closer to the materials used for creating this. The physical work becomes part of the image’s overall effect. Curator: It’s also crucial to remember the romantic ideals that surged within British art at this period. Ruins symbolized the passage of time, the inevitable decline of empires, or, a vision of a new order rising up in defiance. This aesthetic deeply affected not only the ways that art were perceived, but also the labor that goes into building and even preserving historical architectures. Editor: I'm drawn to those tiny figures in the foreground—humanity juxtaposed with the immense structure. They seem to be at the base carrying heavy loads, highlighting the socio-economic implications embedded in the very building itself, where labor, like materials, contributes directly to imperial power. Curator: Precisely. What does the sublime landscape mean for those at the bottom of that societal pyramid? It pushes us to interrogate those themes further by examining the identity of everyone within the walls—not just those at the top. Editor: The artwork asks: Whose stories do we value, and who is relegated to merely supplying resources for a grand spectacle? It also makes me wonder how this piece became popular. Was it more accessible through its print media than another painting with oil on canvas, reaching perhaps a different public through a reproduction that still takes effort and artistry to produce. Curator: This highlights our need for continued criticality around art, moving beyond the simple romanticism of ruins and considering how these landscapes and architectures played, and continue to play, in shaping human interaction and political history. Editor: Exactly! It’s crucial to not separate a material consideration from an interpretation and consideration for how history is not an absolute. Rather it is built, bit by bit, by many different hands.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.