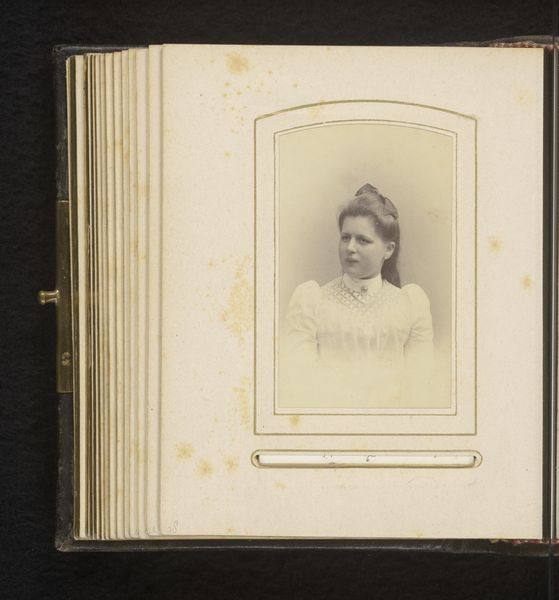

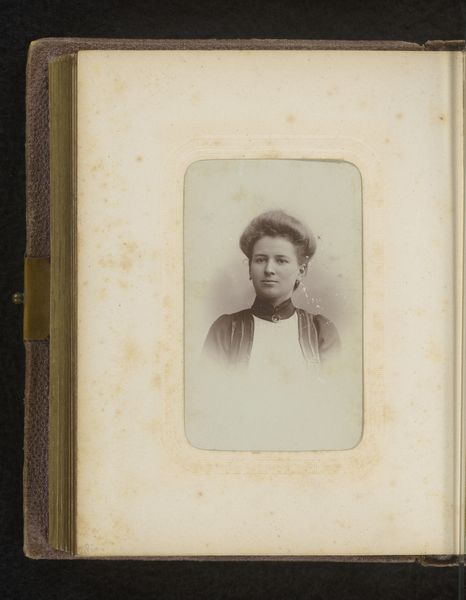

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: height 104 mm, width 65 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let's turn our attention to this captivating portrait, "Portret van een vrouw," an intriguing gelatin-silver print dating from approximately 1870 to 1910, attributed to A. Schlegel. Editor: It immediately strikes me as a piece rooted in the photographic process itself. The subtle gradations, the texture of the paper it speaks to an intimate, hands-on approach to production. There’s an inherent modesty. Curator: Absolutely. This gelatin-silver print really epitomizes that late 19th-century movement towards a more accessible photographic portraiture. Considering the time period, it prompts me to consider the sitter's position within society—was this a means of documenting status, perhaps an attempt at asserting a form of selfhood amidst societal expectations for women? Editor: I’d agree that access to personal portraiture—via photographic print as opposed to painting—becomes a key means by which the rising middle classes articulate and perform their identities. And this print looks to be taken straight from an open photograph album; do you think this was purely personal and private, or an indication of professional self-promotion? Curator: Perhaps both? It captures that transitional era where the boundaries between private and public are increasingly blurred. The woman’s composed gaze and subtle details of her clothing, her buttoned dress for instance, and hair speak of careful construction of her image. The means of production, making this print at least semi-available to the public, becomes key in this case. Editor: And speaking to those details; that soft collared, buttoned-down, possibly homemade striped dress becomes the means to understand the working-class or petite bourgeoisie conditions of its likely maker, too. There is the suggestion here of time, labour, and means to present such a form. Curator: Indeed, this speaks to the rise of the commercial trades of the 19th century. What is compelling is also the fact that we have the trace of her—or the photographer's labor--still preserved, embedded in its material form. The gelatin-silver print provides an access point to the social conditions of labour and gender. Editor: On closer inspection, you can actually observe the paper stock upon which this memory and portrait is built; the book in which its printed. And yet it raises broader questions, also. The means to record, rather than depict; its processes become integral to its existence and the sitter, too. Curator: In the end, its power lies in its ability to incite a narrative that is greater than the sum of its visible parts, of material and representation. It allows us to delve into the identity construction within historical power structures. Editor: And it serves as a reminder to value those historical labour practices involved with building up visual memories of those within a past societal strata, also.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.