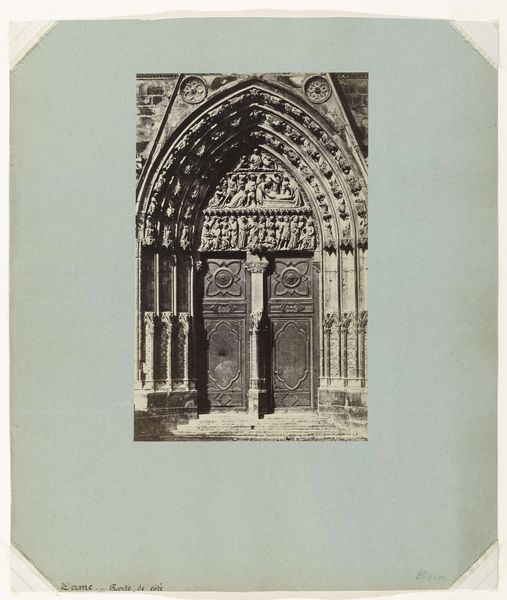

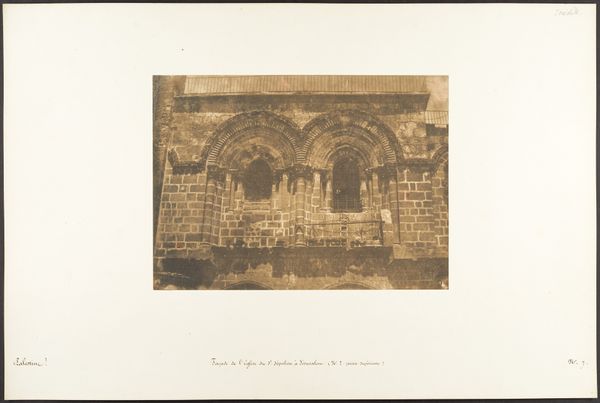

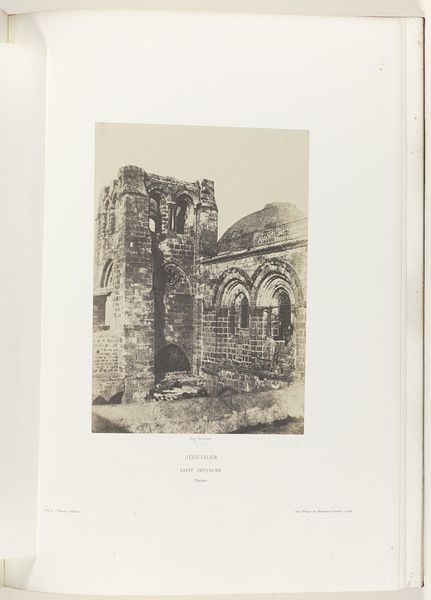

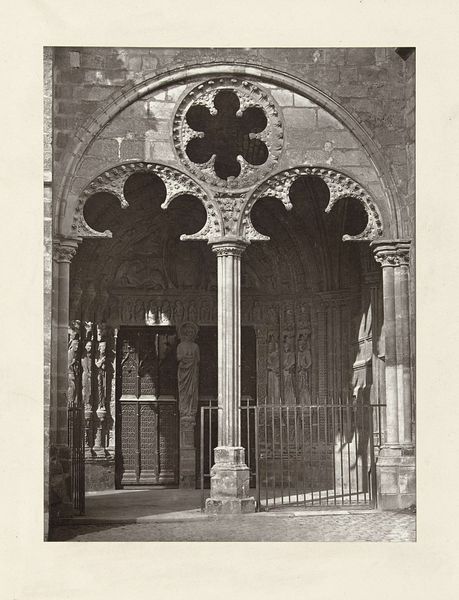

Detail van de noordelijke ingang van de kathedraal in Chartres c. 1853 - 1854

0:00

0:00

charlesmarville

Rijksmuseum

photography, site-specific, albumen-print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

site-specific

#

cityscape

#

albumen-print

#

realism

Dimensions: height 353 mm, width 255 mm, height 612 mm, width 437 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Right, let's dive in. What do you make of this albumen print by Charles Marville? It's called "Detail van de noordelijke ingang van de kathedraal in Chartres," dating back to about 1853 or 1854. Editor: The instant feel is heavy. It’s massive in terms of its stone structure but visually heavy too, weighed down by shadow. Does albumen give it that quality? The almost sepia tone? Curator: It does. The albumen printing process, very popular then, involved coating paper with egg white and silver nitrate, giving it a distinctive sheen and tonal range. Notice how Marville exploits this to capture the texture of the stone and the dramatic play of light and shadow. And indeed the photograph is striking as evidence of the means of construction—stone layered upon stone and held fast, by hands now long since turned to dust. Editor: It’s incredible how that almost makes you *feel* the weight, feel the manual labour. There's also a definite human element fighting against it; there are faces—or hints of faces, watching. Tiny compared to the grand scale, though. Is this just an aesthetic choice or is Marville after something deeper? Curator: Well, he was commissioned to document the city, and the rapid urban development of the time. I think it’s more than aesthetics. It presents a social landscape, charting how architecture functions as a physical record of both creative and physical labor and historical transformations, also suggesting religious context—note the careful ordering, both symmetrical and hierarchical within this monumental religious structure. Editor: Thinking about process—about albumen and light sensitive paper –it strikes me that it feels strange for something so heavy to be captured with something so ephemeral. Did people consider photography to be a lesser medium back then because of its materials? Curator: Absolutely, there was a hierarchy. Photography was often seen as a tool for documentation rather than high art, whereas painting, sculpture, these were seen to be on a superior plane. Marville challenges this, though, really exploring how far photographic material could be taken. Editor: So in some ways, it could be a material study too, right? It is quite remarkable for this quality alone, to take an ephemeral medium and give it a concrete, hefty impact. This makes me question, how do *we* elevate an artwork through our subjective interpretations, against the artist’s intentions and the nature of their medium. Food for thought indeed! Curator: A question that transcends time itself, I think. But in Marville’s image we have the tangible results of skilled, physical labor rendered in a new, modern form.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.