gouache

portrait

gouache

narrative-art

gouache

ancient-egyptian-art

figuration

history-painting

Dimensions: 13.8 x 22.5 cm

Copyright: Public domain

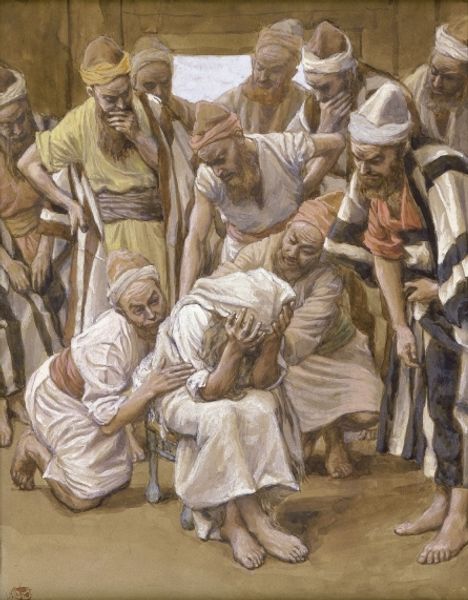

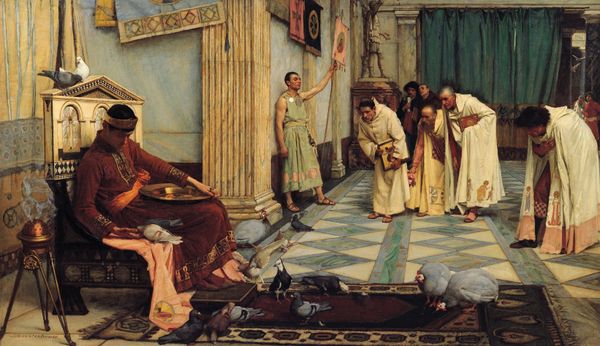

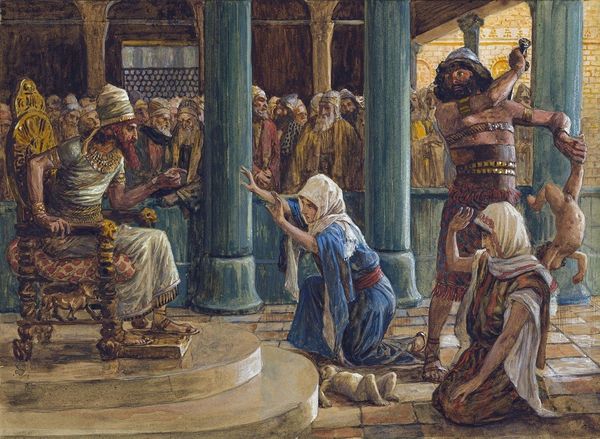

Curator: James Tissot, most recognized for his depictions of fashionable Victorian society, also devoted a considerable amount of work to illustrating scenes from the Old Testament. This gouache painting, "Pharaoh and His Dead Son," dates to 1902, during the final years of his life. Editor: Oh, wow, this one hits you right in the gut, doesn't it? You feel that heavy quiet. And what a study in contrasts—that rigid figure standing defiantly over such still form of the son. Curator: The drama in this composition definitely comes from the story. We see Pharaoh enacting one of the key moments from the Book of Exodus, specifically, the aftermath of the tenth and final plague—the death of the firstborn sons of Egypt. The narrative tension relies on this pivot where Pharaoh must confront his son’s death and let the Israelites go free. Editor: Tissot certainly uses stagecraft here; the painting looks like a paused scene, but full of unspoken lines and impending action. I feel those guys to the left, recoiling—there is something deeply repulsive to them about what's unfolding. I feel caught between a real grief and an unreal performance of defiance. Curator: What's fascinating is how Tissot attempts to present the biblical narrative within an Egyptological context. You see he meticulously researched ancient Egyptian art and architecture, evident in the rendering of the costumes, adornments, and the sarcophagus on which the son lies. This was the era of intense colonial interest in ancient Egyptian culture, shaping a Western understanding that Tissot both participated in and interpreted through his art. Editor: Right. There's something undeniably theatrical about it. But that's what gets you thinking, isn’t it? That performance and what's being suppressed and forced by circumstance. And it really is fascinating that it's a gouache, a sort of mix of watercolour and opaque pigment—adds to the strange luminosity. Curator: I agree, and considering the role of paintings like these as illustrative vehicles for disseminating and, indeed, constructing history for a wider public, understanding his use of the material becomes all the more important. Editor: Indeed. You come face to face with an old story in new colors, and perhaps something unearth is also revealed within us as well.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.