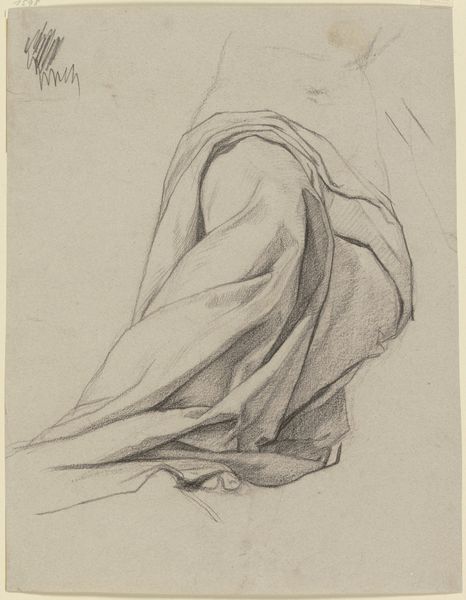

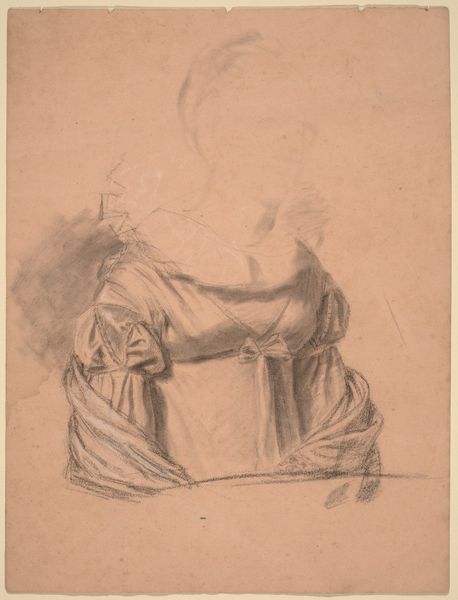

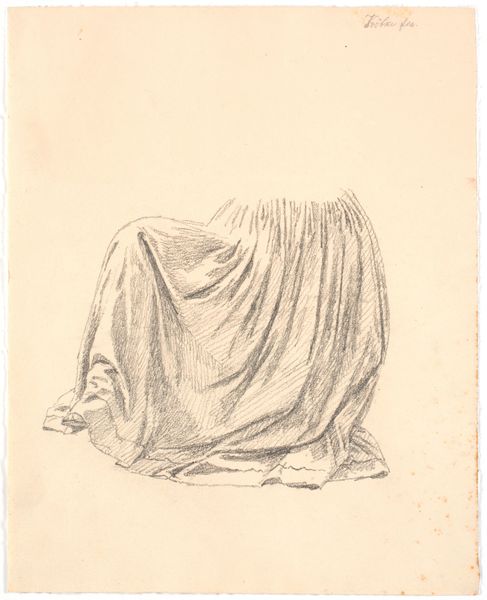

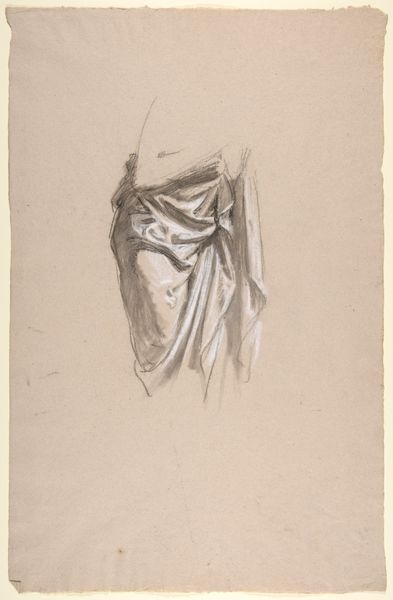

drawing, print, pencil

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

Dimensions: Overall: 12 1/2 x 12 5/16in. (31.7 x 31.2cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

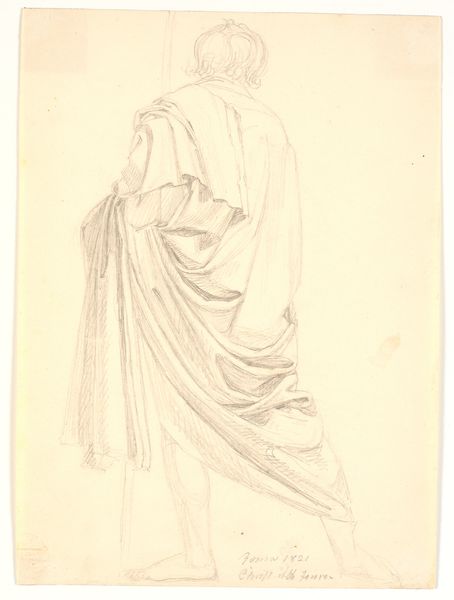

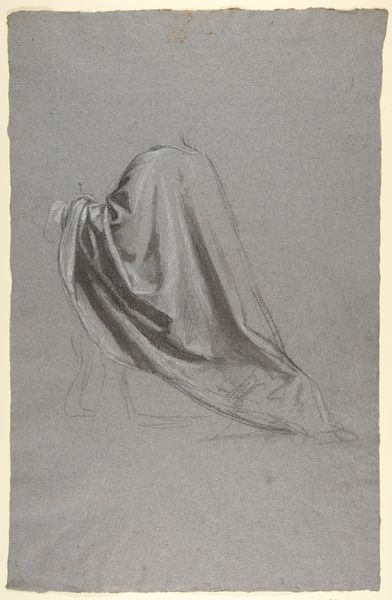

Curator: Alright, so we’re looking at Alexandre Laemlein’s "Kneeling Prelate," a pencil drawing that’s dated sometime between 1830 and 1871. It's currently housed here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: My first impression is... melancholy. There's such a sense of weight, not just in the figure’s pose, but in the almost dreamlike rendering of the cloth. You can sense this inner plea that's both sad and beautiful. Curator: The "weight," as you call it, resonates with the changing socio-political role of the Church during that period. Laemlein, as a portraitist, was keenly aware of how institutions were perceived and wanted to question the long standing practices. A prelate kneeling wasn't just about piety; it reflected shifting power dynamics. Editor: It's incredible how the softness of the pencil contrasts with the rigid structures of the church it seems to be hinting at. There's something unsettling about it – is it a display of devotion, or an acknowledgment of something else entirely? Perhaps an atonement? Curator: Possibly! And note that he employed very minimal details around the head, but gave volume to the clothing. It pushes viewers to think about what is important or should be the focus. Laemlein's technique of near omissions were intended for thoughtful considerations. Editor: Exactly! The absence amplifies the mystery, doesn’t it? Makes it feel almost as if the artist is inviting us to fill in the gaps. It becomes a collaborative experience across time. I keep getting pulled into the folds and lines to understand its meaning. Curator: I agree. Laemlein does an amazing job capturing what I would describe as the institutional anxieties that permeated the period following the Napoleonic era. It challenges us to ask questions about hierarchy, faith, and vulnerability. Editor: It leaves us contemplating more than just a historical image, wouldn’t you say? The lines feel relevant, perhaps especially, now. Curator: Absolutely. "Kneeling Prelate" remains relevant for generations because it forces you to acknowledge how our perspectives, institutional structures, and individual vulnerabilities all affect how we see things. Editor: I love how art, in these small moments, gives us little peeks into how one is feeling but then expands with the collective thought it invokes!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.