#

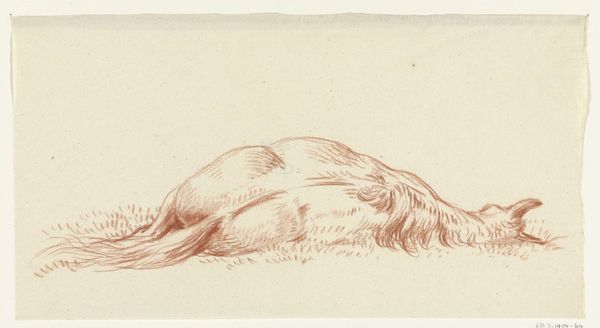

light pencil work

#

pencil sketch

#

botanical illustration

#

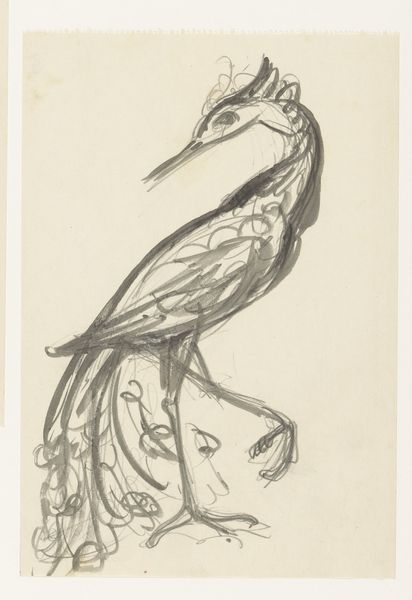

pen-ink sketch

#

botanical drawing

#

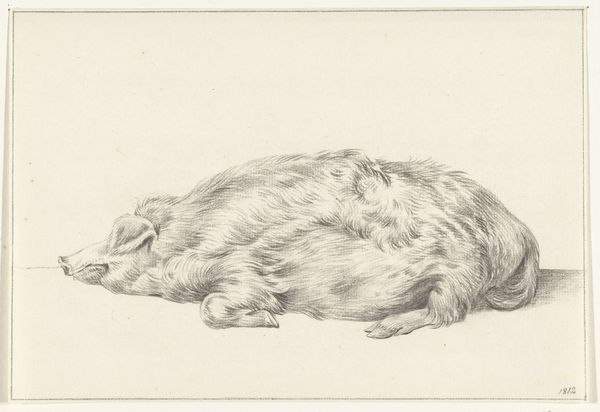

pencil work

#

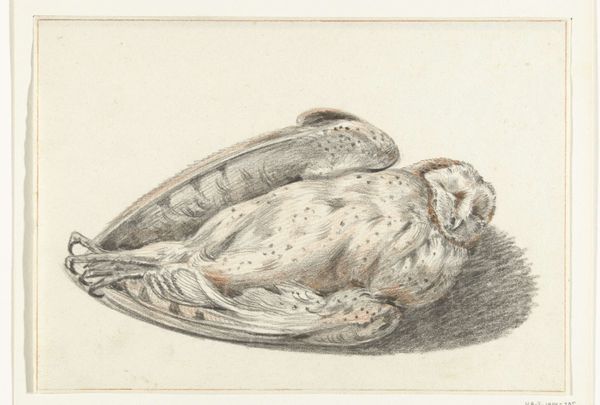

watercolour illustration

#

pencil art

#

botanical art

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 250 mm, width 402 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this is "Een dode kip," or "A Dead Chicken," from 1827, by Jean Bernard, currently residing at the Rijksmuseum. It appears to be a watercolor and pencil drawing. It's quite a detailed sketch, but there’s something unsettling about it, almost scientific in its detachment. What are your initial thoughts? Curator: The clinical precision is key. Think about the rise of scientific naturalism in the 19th century. There's an intense interest in documenting the natural world with objective accuracy. Consider the context: the rise of museums, scientific societies, and the popularization of knowledge. How does depicting something like a dead chicken – usually a signifier of sustenance – as an object of study shift its meaning? Editor: So, instead of seeing it as food, we're meant to analyze its form and texture, almost dissecting it on paper? Curator: Exactly. The politics of display also come into play. By exhibiting this work, the Rijksmuseum implicitly validates this detached, analytical mode of seeing. It elevates a simple animal study to the level of high art, inviting viewers to participate in this scientific gaze. Consider how this contrasts with earlier, perhaps more symbolic or romantic portrayals of animals. Editor: That makes me wonder about the audience at the time. Would they have been accustomed to seeing something so… matter-of-fact? Curator: That's an excellent question. It challenges our assumptions about the evolving tastes and the increasing demand for realistic representation, fueled by both scientific advancements and a changing social landscape. What do you make of the use of pencil and watercolour? How does that contribute to its meaning? Editor: I guess the subtle gradations of tone enhance the realism, making it appear almost lifelike, but drained of color… lifeless. I never really thought about how a museum could "validate" a way of seeing before. Curator: And that’s precisely why historical context and institutional analysis can enrich our appreciation of even the simplest subject matter. I find myself viewing this with new eyes, too, considering the silent cultural forces shaping what we deem worthy of artistic and scholarly attention.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.