Dimensions: height 102 mm, width 172 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

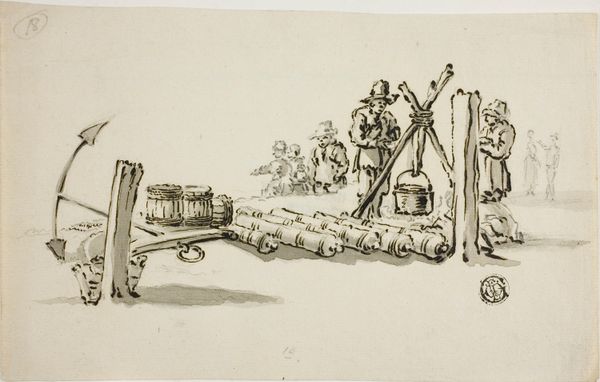

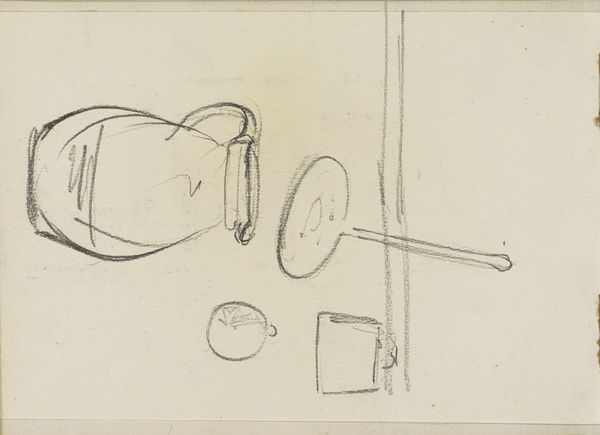

Curator: Looking at this simple sketch, I feel a quiet, almost meditative quality. The artist really focuses on the lines, allowing a space to be present between forms. Editor: Indeed. What we’re seeing here is entitled "Ton aan een rad, een schemel, kan en bakken," rendered in graphite between 1750 and 1793. The artist is Etienne de Lavallée-Poussin, and it's part of the Rijksmuseum collection. The scene seems fairly domestic, and gives a certain charm from that. Curator: Precisely. The composition, focusing on these rather commonplace objects—the barrel, the stool, the pitcher— elevates them through meticulous line work, creating a dialogue between form and negative space, if you see what I mean? The barrel especially, its cylindrical form described through subtly curved parallel lines, speaks volumes about texture and volume with pure economy. Editor: It also offers an intimate glimpse into the tools of daily life. We see the instruments of the kitchen during the Rococo, but we do not witness its participants or consumers. Poussin emphasizes their quiet purpose as tools. I would be curious to research whether such works reflected, for example, contemporary political sentiments during an era of dramatic upheaval and shifting societal structures. Was it seen as a return to an innocent form of art? Curator: I am certain that we cannot remove the artist and the viewer from social discourse, but such consideration detracts us from experiencing it. Consider the use of graphite here; such is interesting from its structural applications. Note how each line contributes not just to outlining objects, but to building their presence, creating a layered composition where shadow and light dance together. Editor: I grant that these domestic tools also carry an undercurrent. This drawing, and ones similar to it, reveal a self-conscious embrace of a supposedly "simple life" to reflect power and structure. Who do these artworks intend to please and who can see them in their time? We, as modern viewers, can read it with less difficulty because art historical study now accepts images from even private life as carrying just as much social meaning as grand history paintings! Curator: So true. Poussin allows each viewer to find these relationships; the interplay of lines guides your attention, fostering a personal reading from within these objects' quiet existences. Editor: Poussin challenges those narratives simply by selecting to display images like these ones. And to contemplate all this meaning packed inside of simple lines is precisely the benefit of visiting the Rijksmuseum, is it not?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.