Bruyntje Springh-in 't-Bed en Flip de Duyvel 1612 - 1652

0:00

0:00

johannesoflucasvandoetechum

Rijksmuseum

#

pencil drawn

#

light pencil work

#

pencil sketch

#

old engraving style

#

personal sketchbook

#

portrait reference

#

pencil drawing

#

limited contrast and shading

#

portrait drawing

#

pencil work

Dimensions: height 134 mm, width 189 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

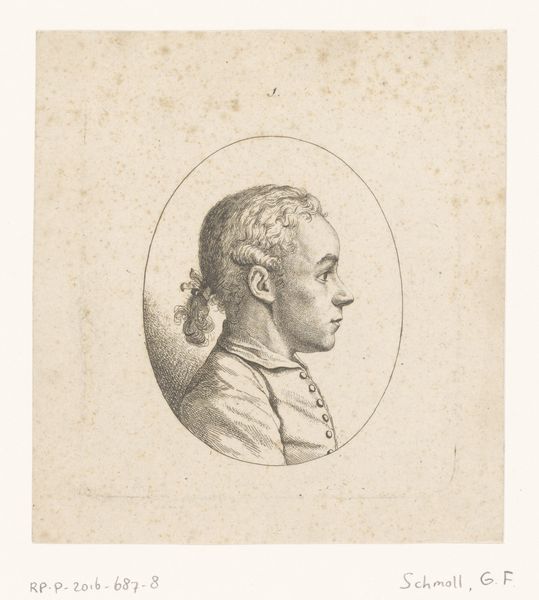

Curator: Welcome. Here we have “Bruyntje Springh-in ‘t-Bed en Flip de Duyvel,” an intriguing piece crafted sometime between 1612 and 1652 by Johannes or Lucas van Doetechum. It's currently housed right here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: The composition immediately strikes me as incredibly formal, almost rigid in its symmetry. Two portraits, framed in ovals, facing forward... There’s a certain detachment to it. Curator: The title offers a clue. “Bruyntje Springh-in ‘t-Bed” roughly translates to “little brown girl jumping into bed,” while “Flip de Duyvel” means “Flip the Devil.” These aren’t just portraits, but rather types, figures embodying specific cultural anxieties. Editor: Yes, and I think the engraving style contributes to that sense of type rather than individual. The precise lines, the lack of dramatic shadow, it all feels very controlled and almost clinical in its execution. Curator: These images circulated widely, playing into prevailing stereotypes about people of African descent and feeding into the complexities of Dutch colonial narratives. It shows how visual culture was deployed to otherize groups of people based on their perceived traits, behaviors, and supposed connection to the infernal realm. Editor: Infernal realm, indeed. There's a disturbing undercurrent in this piece; these neat oval frames almost objectify the subjects further, transforming individuals into specimens for examination, specimens to be cataloged and categorized. Curator: Exactly, and remember that during the 17th century, the concept of "the other" was used to legitimize the enslavement and exploitation of African peoples, something of which, unfortunately, the Dutch participated greatly. This is but a symptom of that thinking made visual. Editor: While seemingly benign upon first viewing, closer consideration of the material qualities exposes a far more malignant historical narrative at work. The cool exactness masks a project of control, power and exploitation. Curator: A potent reminder that even seemingly simple portraits can carry a weighty legacy. Editor: Indeed, seeing how the very form itself is implicated in perpetuating such historical misrepresentation truly highlights how critical evaluation fosters dialogue of both the historical past and its effect on current thought.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.