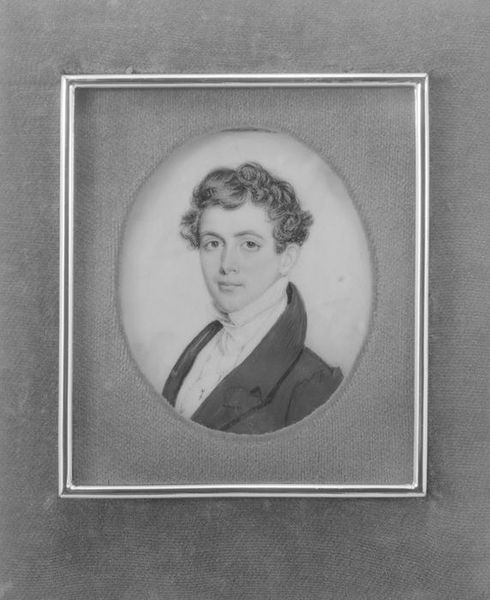

drawing, charcoal

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

charcoal drawing

#

charcoal art

#

framed image

#

romanticism

#

men

#

portrait drawing

#

charcoal

#

history-painting

#

charcoal

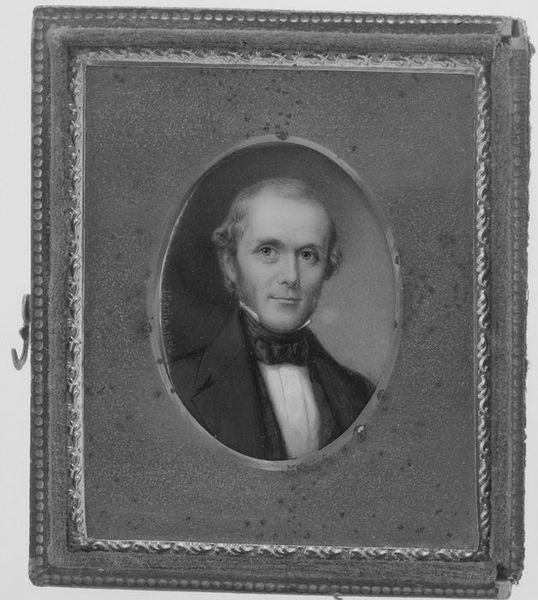

Dimensions: 2 11/16 x 1 7/8 in. (6.8 x 4.9 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

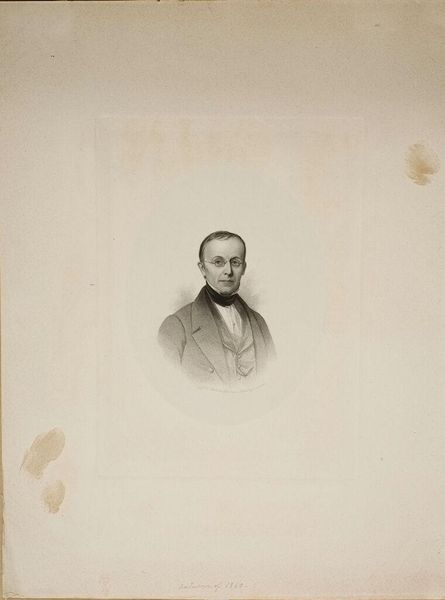

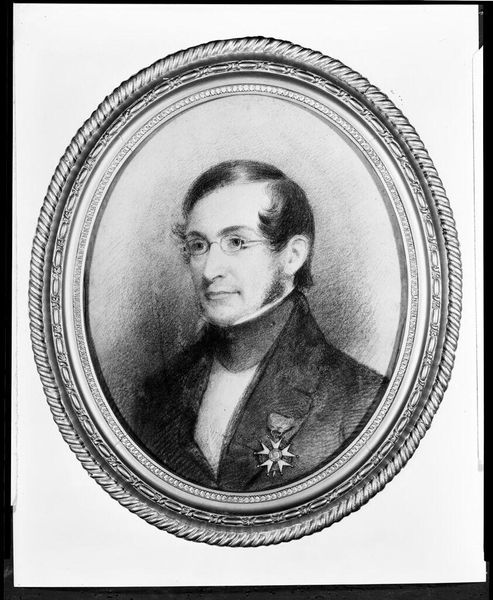

Curator: Behold, Samuel Baldwin Ludlow, an 1838 charcoal drawing now residing at the Met. Something about his gaze feels remarkably modern, wouldn't you say? Editor: Immediately, I see austerity, not just in the man himself but in the economical use of charcoal. I'm interested in the story of its making. Curator: Story of the making is that it captures the Romantic era’s obsession with character—the weight of the man’s existence etched in the charcoal strokes. I wonder what he was thinking? Probably very serious thoughts... Editor: Or, think of the charcoal itself, produced by laborers, processed, transported. Even this portrait's somberness emerges from that social framework and is intimately tied to that production! Was this drawing made for mass consumption, to project an image? Or more privately for intimate display? Curator: Perhaps, in its careful shading, charcoal mirrors the complex layers of societal pressure and personal identity that Samuel Baldwin Ludlow wore, quite literally, in his severe garments. I find this evokes an almost melancholy sense of dignity, don’t you think? Editor: I'd rather unpack those layers, considering that the materiality—charcoal on paper— was fairly inexpensive compared to painted portraits. How does a portrait in charcoal operate in class representation during that period? Curator: But his gaze! Those wire-rimmed spectacles! It’s as if he's peering not just at us but *through* time, judging our fast-paced world...or perhaps concerned with our latest market reports. Who knows? Maybe he was a softy! Editor: Or it's about visibility and labour? A portrait commemorates a subject, sure, but it's also the result of material choices and hands. The creation conditions, even the display of portraiture served economic purposes! Curator: Well, you know, in the end, art speaks differently to each of us. Editor: Exactly! And that's because even what we consider “high art” like portraiture is entwined with the everyday material conditions and the social landscape of its time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.