photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

realism

Dimensions: height 83 mm, width 173 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

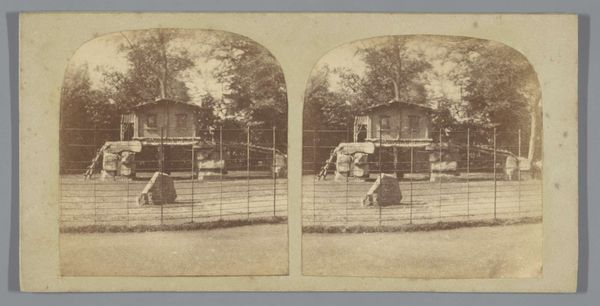

Curator: Before us, we have a gelatin-silver print from sometime between 1860 and 1885 by Pieter Oosterhuis entitled "Gezicht op gesticht Meerenberg in Bloemendaal", depicting the Meerenberg asylum. It's a fascinating example of early architectural photography. Editor: The composition immediately strikes me. That picket fence dominating the foreground feels like a deliberate barrier, creating a sense of separation from the building beyond. What effect do you think that has? Curator: I think it speaks to the way such institutions were perceived then—as places set apart, both physically and socially. There’s a symbolic containment present. Mental illness, then, carried a profound stigma, and architecture reinforced this. The asylum appears solid, imposing, yet strangely impersonal. Editor: Indeed, the building's façade, while regular in its windows, lacks warmth. The lack of direct human presence in the image contributes to this austere feeling. Notice also how the tones tend to monochrome shades, almost draining all vitality. Curator: Oosterhuis, being a Realist, probably aimed for documentary objectivity, yet the visual choices undoubtedly shaped our experience. Consider how the broken chimney emphasizes time and decay. It subtly foreshadows decline or malfunction. The tall skinny trees contrast with it like silent watchmen or grieving mourners, as if guarding sad secrets. Editor: I see what you mean. And yet the placement of the chimney right of centre guides the viewer’s gaze towards the building, creating a strong focal point and structural symmetry along vertical lines. Did this institution represent a social structure? Curator: Absolutely. Mental asylums had been seen as modern social tools of progress. But also tools of control and confinement, often isolating individuals from society and normal living. The symbolic connotations speak directly to those conflicting meanings. It brings to mind a similar effect in Dorothea Lange’s portraits during the Depression. Editor: In this context, the photograph transforms from a mere document to an emotional, perhaps even critical statement. That's fascinating to me. Thank you for making those visual relationships clear, linking composition to emotional meaning. Curator: It's precisely through studying the convergence of those symbols—social, architectural, psychological—that this image gains enduring meaning beyond its immediate subject. It acts as a portal into understanding a forgotten or deliberately concealed past.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.