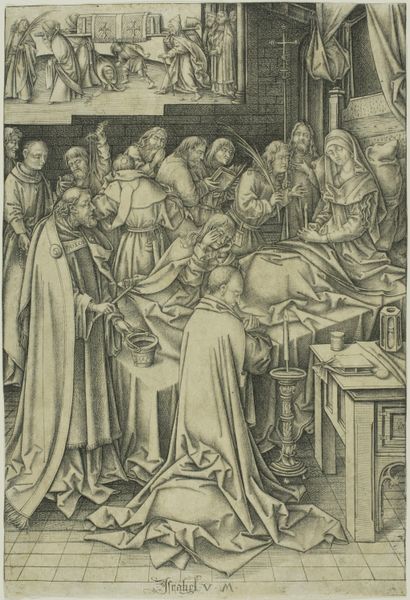

print, intaglio, engraving

#

medieval

#

narrative-art

# print

#

intaglio

#

figuration

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: 208 mm (height) x 145 mm (width) (bladmaal)

Curator: Welcome. We’re standing before Israhel van Meckenem's engraving, "Christ at Emmaus," dating between 1440 and 1503. It’s currently held at the Statens Museum for Kunst. Editor: The initial impression is the overwhelming density of the line work. It’s incredible – the sheer labor invested to create light and shadow in the scene, even creating depth with different textures within the single scene. Curator: Indeed. Meckenem's background as a goldsmith informs his detailed, almost miniaturist, approach to engraving. This particular print exemplifies how religious narratives permeated daily life and culture in the Northern Renaissance. Notice, too, how Meckenem situates the biblical story in a contemporary domestic setting. Editor: Absolutely, and what’s interesting is the contrast between the material reality presented – the food, the architecture, even the servant's costume – with the implied spiritual event. How are those mundane items elevated to religious status here through the labor in representation? I wonder, were these affordable enough for even working-class households, further cementing this narrative within their lived experiences? Curator: That's a perceptive point. Meckenem’s prints, reproduced in multiples, served to disseminate not only religious imagery but also the prevailing social order. The depiction of Christ at a communal meal would have resonated powerfully with notions of charity and fellowship, both promoted by the Church. Editor: I can't help but wonder about the process – the intense manual skill required. The very act of engraving becomes a devotional practice in itself. Each precisely etched line a testament to faith. And it makes you think of the value placed on skilled craftsmanship in the medieval and early Renaissance workshops, and what bearing it has to the status of an "artwork." Curator: It absolutely complicates that picture. To understand Meckenem is to look at the economics of art production and reproduction in the late 15th century. This was, in a very real sense, an early form of mass media, helping to shape popular conceptions of biblical stories. Editor: This reminds me of how crucial printmaking was for spreading ideas to the populace, bypassing traditional aristocratic control. So interesting how something so tied to manual labor becomes such a powerful tool for information. Well, thinking about that level of work that’s gone into its making, that detail is incredible. Thanks for pointing this work out. Curator: And thank you, that makes it such a pleasure to have another way of thinking through this.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.