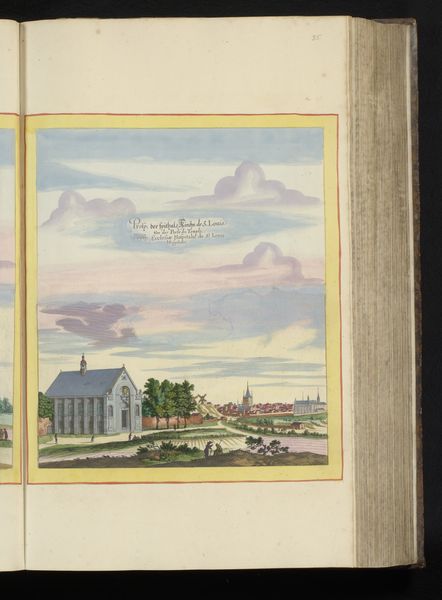

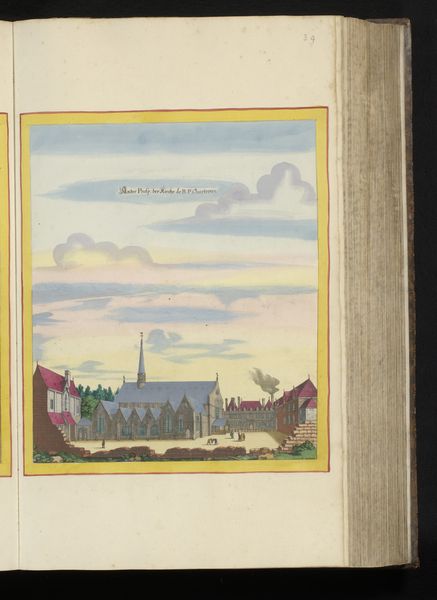

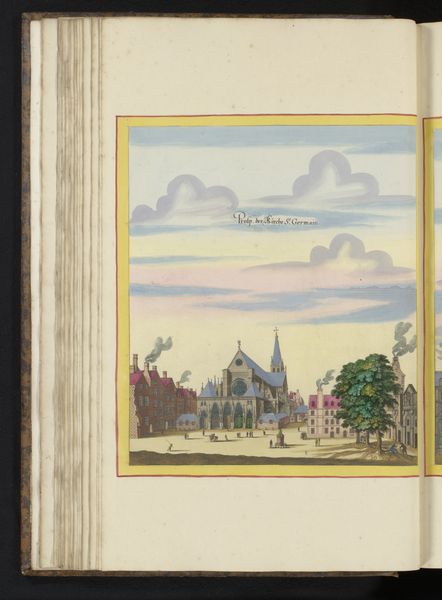

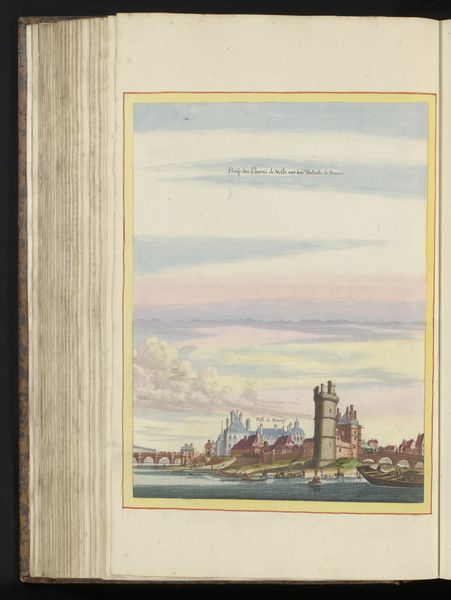

Gezicht op de priorijkerk van Saint-Martin-des-Champs te Parijs 1655

0:00

0:00

matthausiimerian

Rijksmuseum

painting, watercolor

#

baroque

#

painting

#

landscape

#

watercolor

#

coloured pencil

#

cityscape

#

watercolour illustration

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 333 mm, width 285 mm, height 534 mm, width 330 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

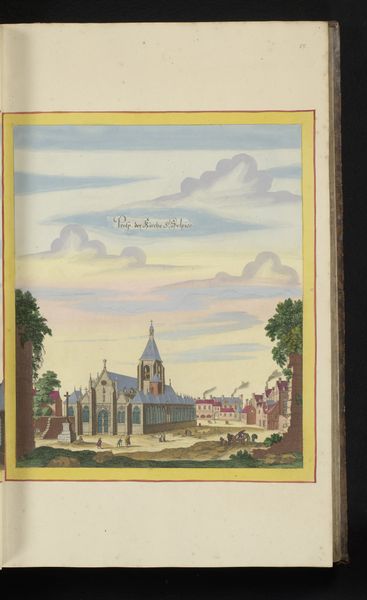

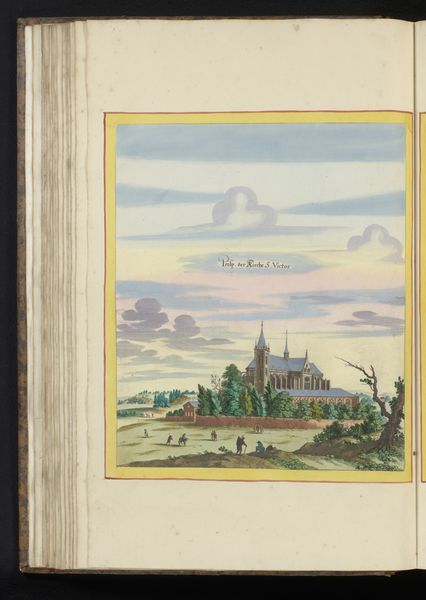

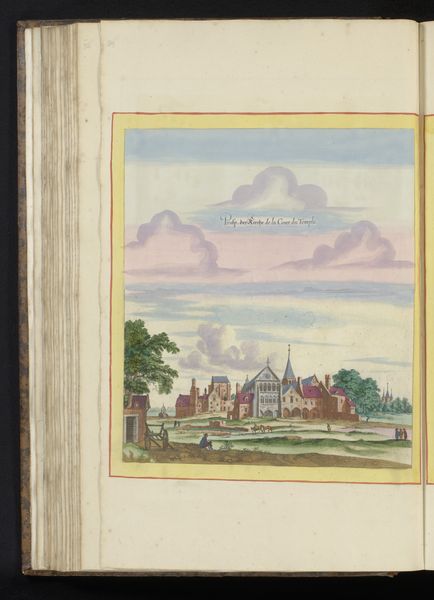

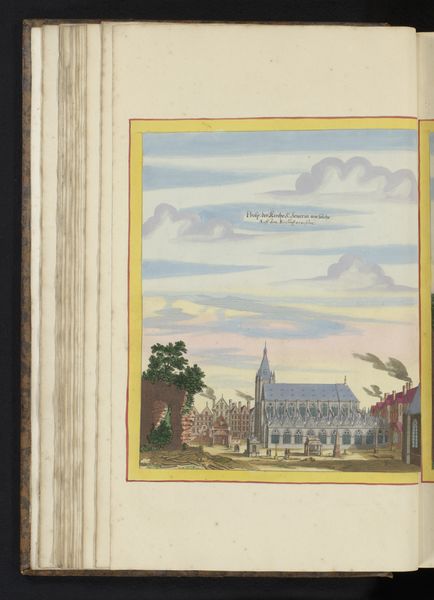

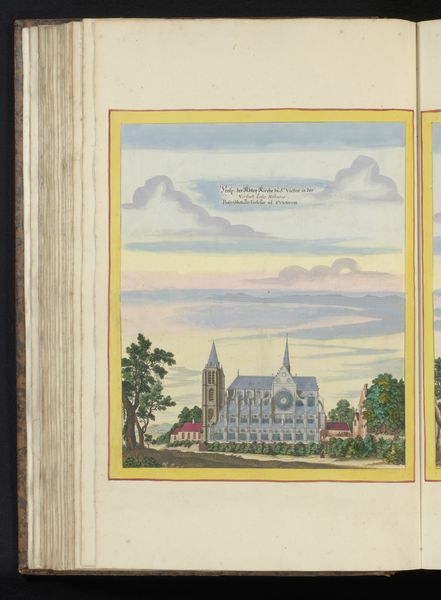

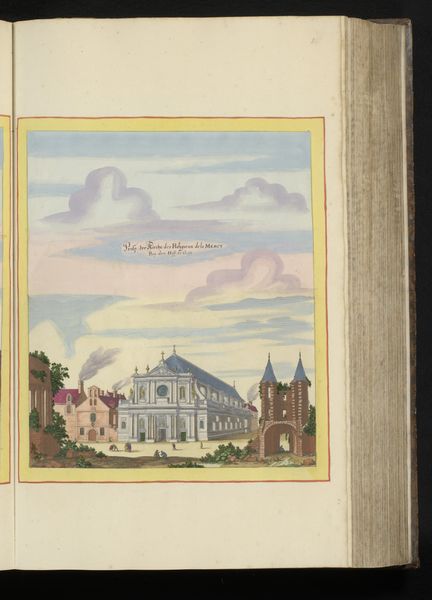

Curator: Matthäus Merian the Younger created this watercolor landscape in 1655. It's titled "Gezicht op de priorijkerk van Saint-Martin-des-Champs te Parijs"—a view of the priory church of Saint-Martin-des-Champs in Paris, now at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My initial reaction is calm. It's peaceful, you know? There's a gentle stillness to the scene that I find incredibly soothing. Almost like a dream… Curator: Dreams were rarely egalitarian back then, were they? Situated in mid-17th century Paris, this cityscape represents more than just aesthetic appreciation. It speaks volumes about the relationship between the Church, urban space, and social power. The way the priory dominates the composition, its towering presence, tells us a lot about its influence. Editor: True. I do see the domination, now that you mention it, but what gets me is how it captures a world on the cusp of…well, change, always—but *this* feels significant. It makes me think about my neighborhood and about people trying to coexist. It is quite elegant for such a rigid period. Curator: I think that’s astute. The Church's physical and ideological weight certainly impacted urban development. Access, resources, social control… landscape paintings are rarely "just" pretty pictures. I see power dynamics at play in something as ostensibly simple as where someone places a horizon line. Editor: Okay, power horizon lines! I'll need to use that one later. But yes, there's a quiet drama there, the way those Baroque clouds are so dramatic but rendered so softly...It also sparks something about human resilience, perhaps a stubborn persistence against…absolutism? Maybe I'm romanticizing things! Curator: Perhaps a touch. The historical lens compels us to look deeper. In 1655, France was solidifying its absolute monarchy, its religious policies becoming increasingly oppressive. Even seemingly neutral scenes carry encoded meanings related to resistance or complicity. We always bring our biases to what is aesthetically appealing, so to decode those unspoken dynamics is key for today's conversations on political expression. Editor: Right, like asking myself why I was initially so soothed. Makes me wonder what my responsibilities are in a chaotic world. The little details—like how tiny the people look in comparison to the church–make me appreciate small, simple rebellions! I came into this ready to drift, but instead it is thought-provoking. Curator: Indeed. Art from any period encourages reflection. By understanding its contexts, we deepen our comprehension of art’s role and how historical frameworks affect modern narratives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.