Dimensions: height 272 mm, width 375 mm, height 316 mm, width 413 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

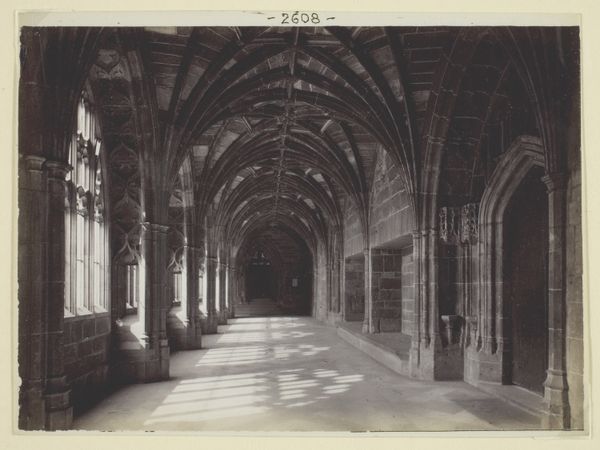

Curator: Before us, we have an albumen print by Médéric Mieusement, titled "Kasteel van Saint-Germain-en-Laye," taken sometime between 1870 and 1890. It resides here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It's imposing, isn't it? A stoic giant rendered in sepia. There’s something hauntingly static about it; like the air itself is heavy with history. The scale of that building is immense, dwarfing everything else. Curator: Indeed. What we see here represents more than mere architecture; the Saint-Germain-en-Laye castle served as a royal residence for centuries. It played a significant role in French political and cultural life. Consider how photography at this time sought to legitimize and document institutions and power structures. Editor: And think about the material reality of producing an image like this in that era. Albumen prints were labor-intensive, requiring careful preparation of the paper with egg whites and silver nitrate. This was skilled work, creating a commodity consumed by an eager, image-hungry public. We often overlook the sheer craft involved. Curator: That craft, however, also reinforces a certain social hierarchy. Photography, initially expensive, solidified the roles of the elite. It depicted their spaces, their power... perpetuating a particular narrative of progress and permanence. Editor: Exactly. The choice of albumen – a fragile, organic material – contrasts sharply with the image's message of strength and endurance. These prints, prone to fading and damage, remind us that even monuments crumble, empires decline, and photographs, despite their documentary intent, are inherently unstable objects, much like our memories. Curator: The architectural style itself harkens back to Neoclassicism, evoking ideas of order, reason, and a return to the grandeur of antiquity. This aesthetic choice was no accident; it served to legitimize the ruling powers of the time by aligning them with a perceived golden age. Editor: Yes, a manufactured golden age, built quite literally by armies of anonymous laborers quarrying stone and crafting these immense structures. They are essentially erased from the photographic record. The photo renders an almost alienating stillness. You feel their absence as a tangible void. Curator: Looking at it again through our discussion, I am reminded of how constructed such images really are and the role they played in constructing the idea of national identity and historical narrative. Editor: And I’m left contemplating how we consume and perpetuate such visual rhetoric, blind to the often brutal processes that birthed them. An uncomfortable beauty, to say the least.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.