#

portrait

#

water colours

#

oil painting

#

watercolor

Dimensions: overall: 47.2 x 62.3 cm (18 9/16 x 24 1/2 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

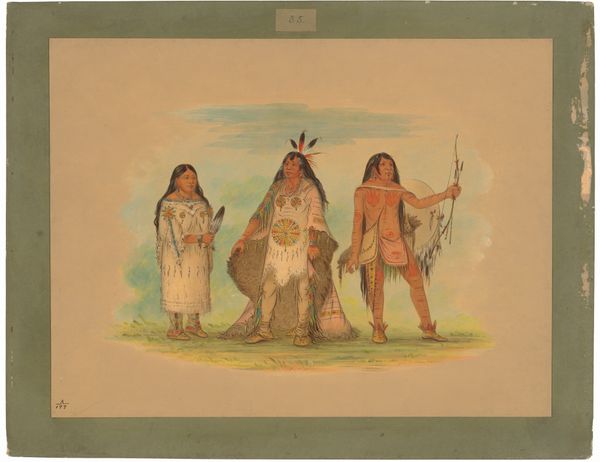

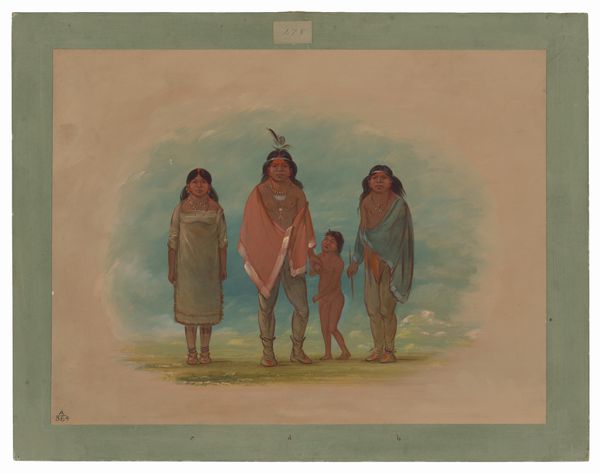

Curator: What strikes me immediately about George Catlin’s "Puncah Indians," painted around 1861, is its quiet dignity. There's a solemn presence conveyed through these three figures rendered in delicate watercolors. Editor: Yes, there's a posed serenity, but for me, this is laced with a heavy awareness of cultural disruption. The date is significant, isn’t it? Right on the cusp of profound shifts in the lives of Indigenous communities due to settler expansion. Curator: Indeed. Catlin, of course, is known for his project to document Native American life. And here, we have three Puncah individuals presented with great detail in their attire and ornamentation. Look at the sun motif on the left figure’s blanket, a universal symbol across many cultures, of life-giving energy. Editor: Absolutely, and I see that as both celebration and preservation. He is documenting, yes, but what’s the impact of this work? Is it honoring, or is it participating in a colonial project that’s ‘collecting’ cultures? Those items they wear–they are markers of identity but are reduced to aesthetic objects, removed from everyday existence and societal importance. Curator: That tension is precisely what makes it a compelling historical artifact. Take the figure in the center, possibly a leader or person of significance, adorned with feathers and a distinct garment. These are powerful visual statements that spoke of lineage and status. Editor: Precisely. They are individual assertions, yet within a paradigm that will deny them collective agency. Also, consider Catlin's role; the white gaze that frames and interprets this culture for a predominantly white audience. It’s impossible to divorce the image from that power dynamic. Curator: However, his detailed depictions offer invaluable insights into the material culture of the Puncah people. The subtleties within the rendering— the unique hair ornamentation, the beaded details – these resonate with established symbolic visual forms that link us with those cultures still. Editor: That visual record is valuable, undoubtedly. Yet we need to continually examine through whose lens we are viewing history, understanding the artist’s social positioning to avoid reinforcing inequalities. We also need to ask about what happened to the objects Catlin depicted. Were they preserved or plundered? Curator: I agree, a more profound understanding stems from an intersectional examination. These individuals once alive now linger as ghosts in painted frames, representing communities pushed to the periphery by historical, relentless pressure. It invites, ultimately, an even more critical contemplation of that history and a profound empathy. Editor: A stark reminder, I’d say, that our engagement with any cultural artifact demands a perpetual reflection.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.