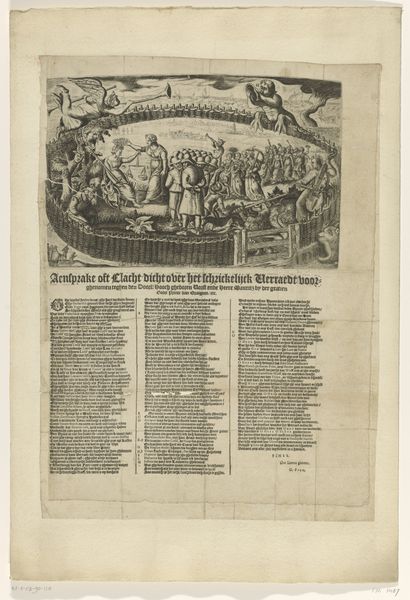

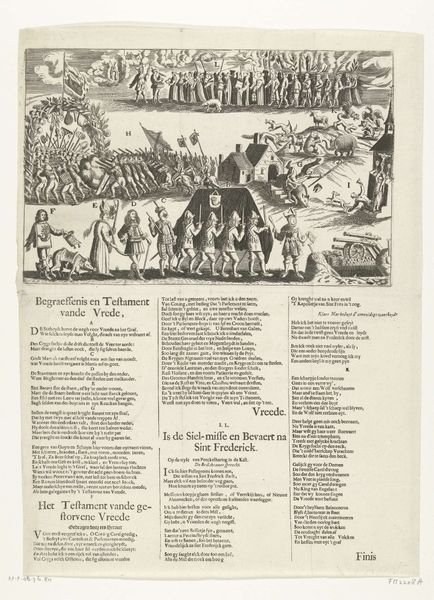

De geestelyke loterye en gelukkige haeve voor d'afgestorvene christene / geloovige zielen 1800 - 1833

0:00

0:00

philippusjacobusbrepols

Rijksmuseum

graphic-art, print, paper, ink, engraving

#

graphic-art

# print

#

paper

#

pencil

#

ink

#

pen work

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 398 mm, width 338 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

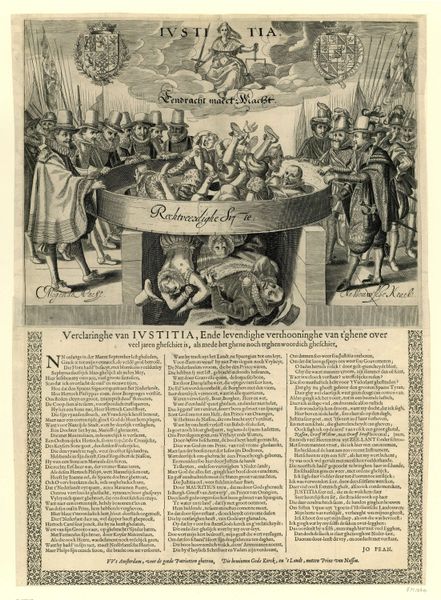

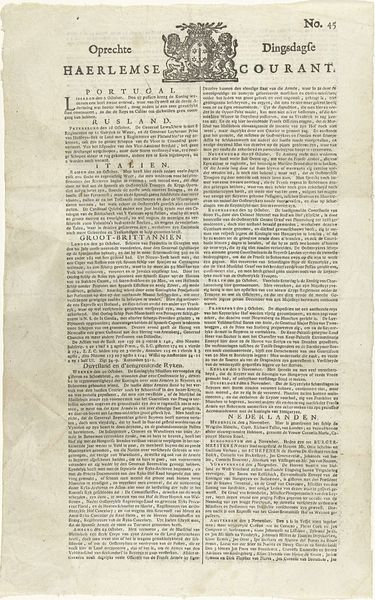

Curator: Welcome to the Rijksmuseum. Here, we’re examining “De geestelyke loterye en gelukkige haeve voor d'afgestorvene christene / geloovige zielen,” or "The spiritual lottery and happy refuge for the deceased Christian / believing souls,” a print made between 1800 and 1833 by Philippus Jacobus Brepols. Editor: Immediately striking is its frenetic energy! A swarm of bodies seems to writhe within a crowded composition. I’m interested in the process – it's an engraving, printed on paper… you can see the labor, the almost frantic reproduction implied in such a busy design. Curator: Indeed. The print functions as a type of devotional aid. Its symbolic structure depicts souls released from purgatory by prayer, visualised almost like sparks ascending to Heaven. There’s a strong sense of collective redemption. Editor: So, the mechanical reproduction of these images allows for a mass dissemination of specific theological content...an instruction manual of sorts for alleviating earthly suffering with mass-produced gestures and images. Fascinating from the point of view of labor and also, spiritual manipulation! Curator: Yes, the imagery acts as a symbolic economy—offerings of prayer exchangeable for spiritual release. Notice how certain figures appear brighter than others, signifying their state of grace through a complex visual hierarchy. Editor: Looking closer, the linear quality of the print gives it an almost diagrammatic feel, further reinforcing this exchange. It strips away the emotional intensity, transforming the act of faith into an easily repeatable, marketable action, an early mass-produced visualization of spiritual relief, promising collective effervescence but through individual labour. Curator: That’s a valid observation. The lottery aspect evokes an active participation in one's salvation, but also, the anxiety that such imagery must’ve evoked regarding death and judgment. The combination, quite a poignant cocktail of faith and human insecurity... Editor: True, you’re not wrong in saying it is more complicated than just consumerist marketing, the piece works with pre-existing social tensions within religious life! Ultimately, though, it underscores how religious experience was packaged and circulated within early modern society, and what materials, in the end, were consumed to feed that devotion. Curator: A fascinating exploration of devotion and visual economy—certainly food for thought. Editor: Definitely reveals art's complicated role within cultural systems. Thanks!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.