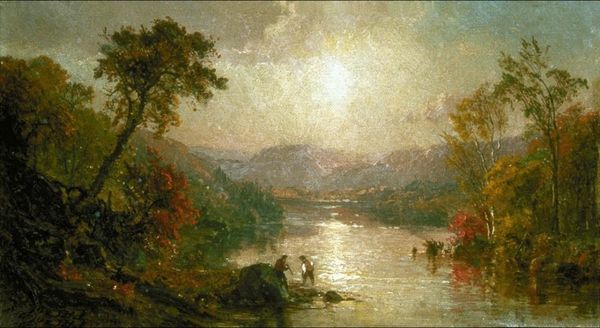

Copyright: Public domain

Curator: We are looking at "The River of Light," painted in 1877 by Frederic Edwin Church. Editor: My first impression is quiet awe; the subdued light and detailed foliage feel incredibly peaceful. The realism makes me want to feel the humidity in the air, to reach out and touch the bark on those trees. Curator: Church was a key figure in the Hudson River School, and this work encapsulates many of their core principles, notably the transcendental power of nature. The "river of light" itself symbolizes the divine presence in the natural world. Note the subtle placement of the sun almost dead center, an explicit symbol of that divinity. Editor: Thinking about the context of its making, I wonder about the global reach required for Church to depict this specific kind of landscape. His choices weren't accidental, considering the technology of pigments, global exchange and trade. How dependent was a canvas like this on colonial structures to source not just inspiration, but the material components? Curator: Precisely! It serves as a kind of window into an idealized vision of nature but a culturally charged landscape. I also notice the symbolism of growth and decay so prominent here – those towering trees in the foreground stand in stark contrast to the sun-drenched water leading off into what might symbolize the future or heaven. Editor: Thinking more on materiality: that luminous effect would rely on very refined techniques and precise applications of oil paint. This was labor. It's about a highly skilled craftsman at work, but the picture plane largely obscures that labor to construct the illusion of perfect nature, ready for contemplation. Curator: And let's not overlook that it's called "The River of Light." In religious symbolism, light equals knowledge, divine inspiration, guidance. That’s the tradition Church is operating in and responding to. What a beautiful commentary. Editor: I'm left wondering how "untouched" landscapes can be depicted – and how we continue to see them even today. I appreciate how it forces a deeper look at nature, labor, and global connections, and makes us reconsider where our raw materials come from. Curator: I concur, this piece provides fertile ground for analyzing not only visuality but the very meaning we ascribe to places and symbols, old and new.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.