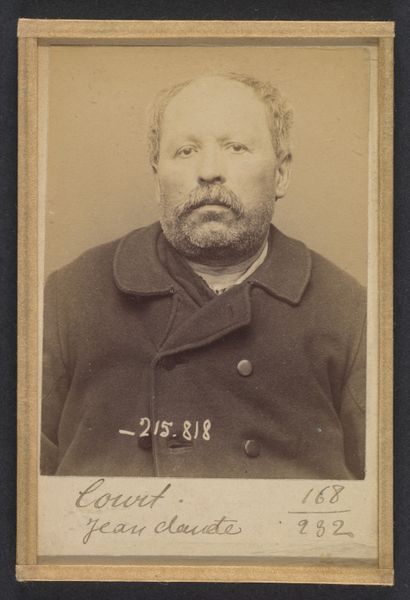

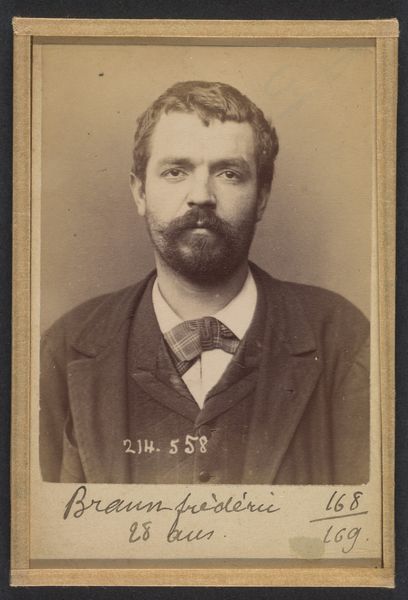

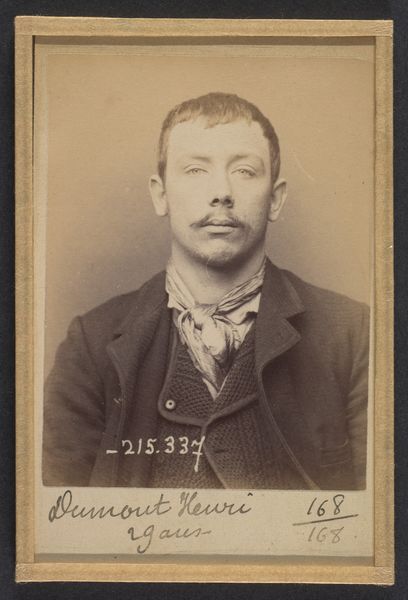

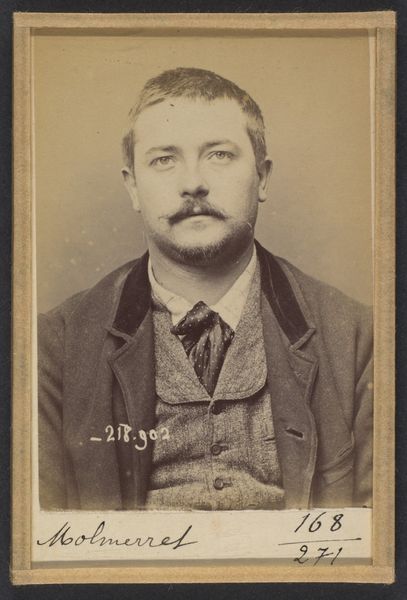

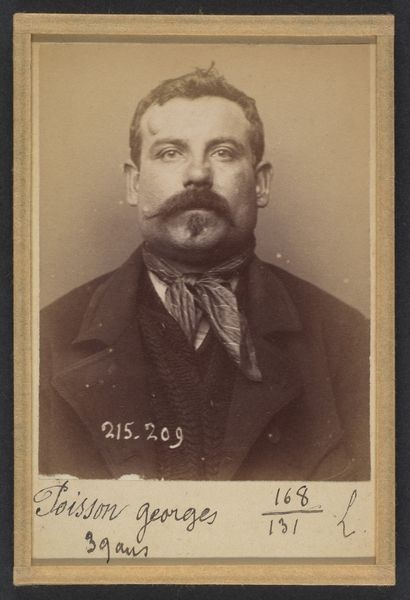

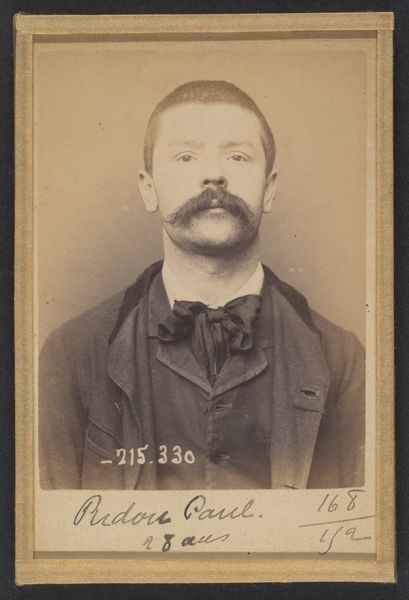

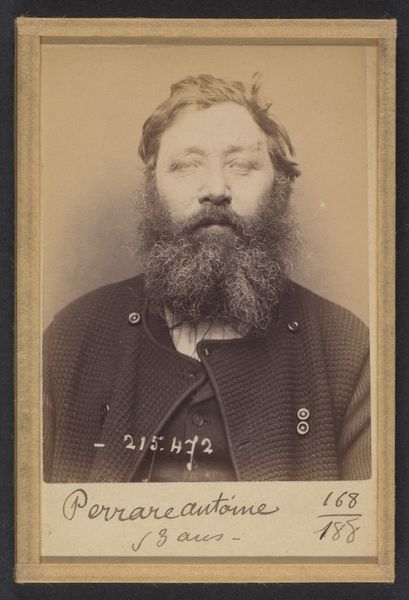

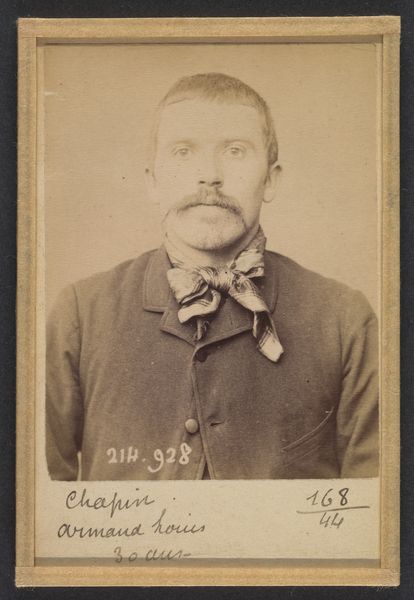

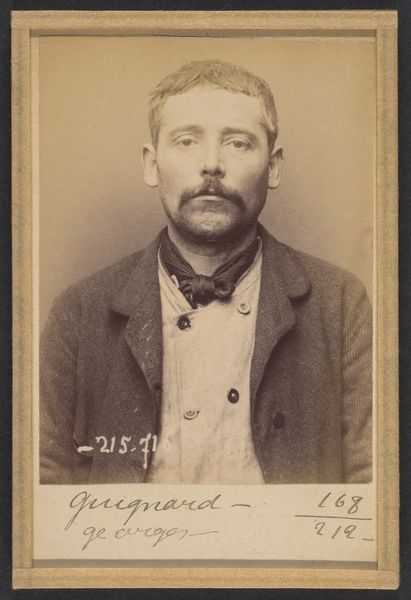

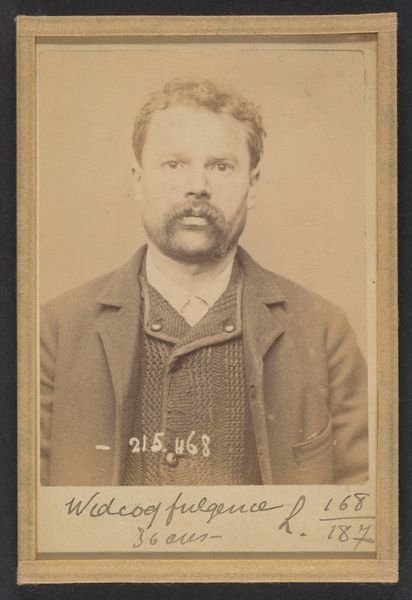

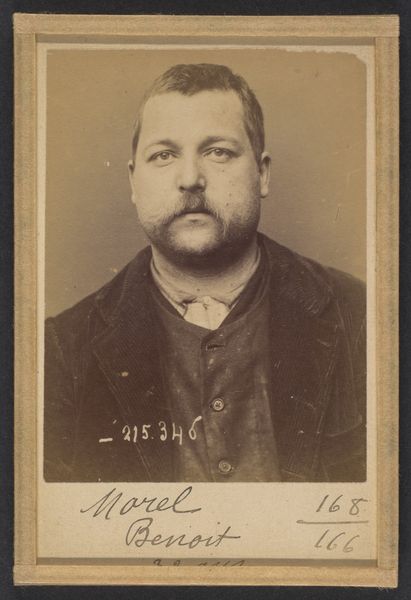

Hourt. Jean. 34 (ou 35) ans, né à Reims (Marne). Menuisier. Anarchiste. 4/3/94. 1894

0:00

0:00

photography

#

portrait

#

portrait

#

photography

#

realism

Dimensions: 10.5 x 7 x 0.5 cm (4 1/8 x 2 3/4 x 3/16 in.) each

Copyright: Public Domain

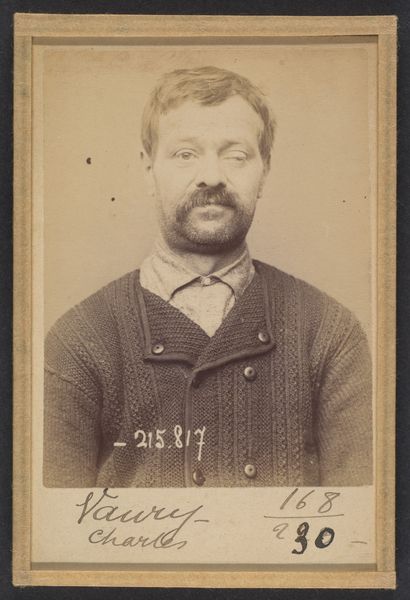

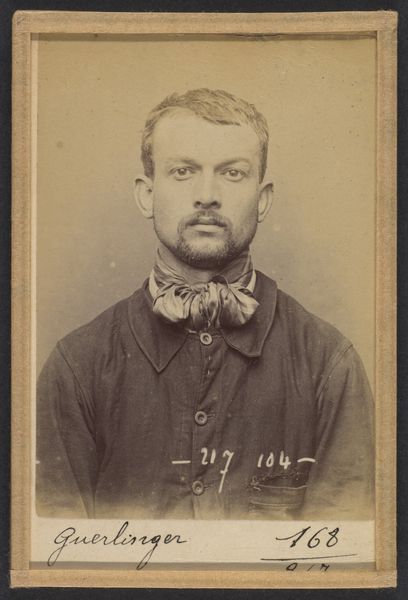

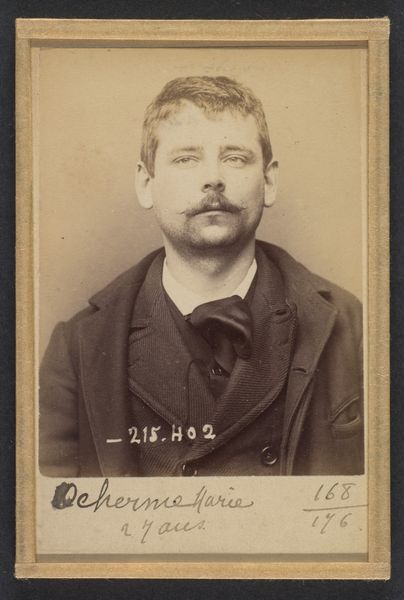

Curator: This photographic portrait, created by Alphonse Bertillon in 1894, is titled "Hourt. Jean. 34 (ou 35) ans, né à Reims (Marne). Menuisier. Anarchiste. 4/3/94." It’s currently held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: It strikes me as both stark and intimate. There's an almost palpable weight in the sitter's gaze. Given the photographic method of the era, how was Bertillon dealing with capturing anarchists at this time? Curator: Bertillon's method, known as "Bertillonage," involved anthropometric measurements and photography as a way to identify and track individuals, primarily within the criminal justice system. Anarchists, viewed as threats to the social order, were certainly targets of such surveillance. We can think of the labor involved in photography in the late 19th century versus labor today in surveilling communities. Editor: Indeed. Consider the societal anxieties swirling around anarchist movements during that period. His labeling of the subject not just with his age and occupation, but also his political leaning— "Anarchiste"—effectively positions him as a threat. How much do you believe this representation may have had an impact? Curator: It definitely highlights how easily systems of identification can be weaponized. His occupation as a joiner is almost secondary, whereas that label ‘anarchist’ situates him firmly within a politically charged narrative. Photography becomes not a neutral recording, but a tool for constructing a specific image of this person, aligning him with danger and subversion. Editor: Absolutely. Let's talk about the materiality of the print. I wonder about the specific photographic process. The monochrome palette focuses the viewer so acutely on the subject’s face and the details of his attire; a certain wear to his coat or knot of his scarf, giving you a certain perspective on this individual. Curator: The choice of photography as the medium here reinforces the intention of empirical observation. We have to remember that Bertillon's process, while supposedly objective, was embedded within systems of power and prejudice. How did that effect the materials he selected? Editor: Yes, what’s represented and the means used to do it, particularly in bureaucratic record-keeping, were inherently enmeshed with political and societal structures. This image really encapsulates that tension between objective record and subjective interpretation. Curator: I find the work profoundly relevant. In considering the photograph, we're also invited to confront enduring questions of surveillance, power, and the representation of identity.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.