painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

figurative

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

figuration

#

romanticism

#

portrait drawing

#

realism

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

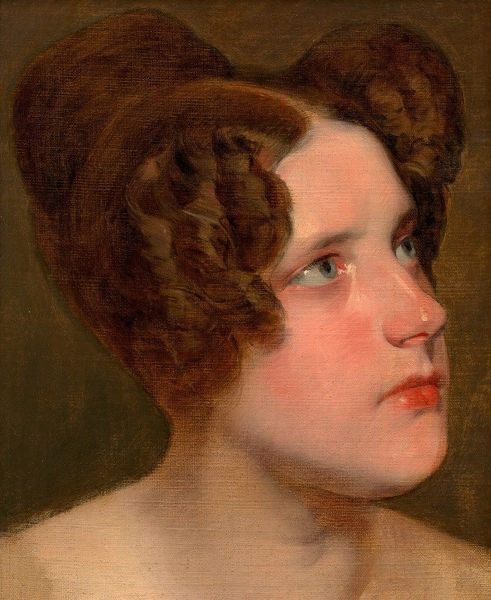

Editor: Here we have Gustave Courbet's "Portrait de Zélie Courbet" from 1842, rendered in oil on canvas. There’s something quite delicate about it, almost melancholic. What strikes me is the incredibly smooth surface; how was that achieved at this time? Curator: The smoothness is key, isn’t it? Courbet, even this early, is grappling with representation. The almost porcelain-like skin is achieved through careful layering and blending of the oil paint, which involved labour but it hides it, doesn’t it? But look at the way her clothing seems secondary, the texture of the fabric is only gestured towards. Editor: I see what you mean. There is an imbalance in how she’s presented... the emphasis on her face seems idealized, even. Curator: Precisely! Now consider the social context. Portraits like this were often commissioned, aren't they? Think of the Courbet family and their resources: where would Courbet have learnt painting skills at that moment of history? What materials were available to him? This idealisation is less about pure aesthetics, and more about reflecting or constructing social standing. This piece makes us ask whose idea of beauty is portrayed? Editor: So it’s not just a portrait, it’s a statement of the Courbet's own bourgeoise status, made using the tools and values available to them. I hadn't thought of the availability of the paints themselves being so critical to understanding this. Curator: Exactly! We understand art best when we look at its creation and what that production meant. Editor: It makes you rethink what you value when looking at art. Thanks. Curator: Indeed, and that’s precisely what a materialist reading encourages: to think critically about the relationship between production, art, and society.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.