daguerreotype, photography

#

scenic

#

natural shape and form

#

countryside

#

landscape

#

daguerreotype

#

river

#

ancient-egyptian-art

#

nature

#

outdoor photography

#

photography

#

outdoor scenery

#

nature heavy

#

outdoor activity

#

outdoorsy

#

shadow overcast

Dimensions: Image: 23.7 x 30.9 cm (9 5/16 x 12 3/16 in.) Mount: 40 x 51.8 cm (15 3/4 x 20 3/8 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

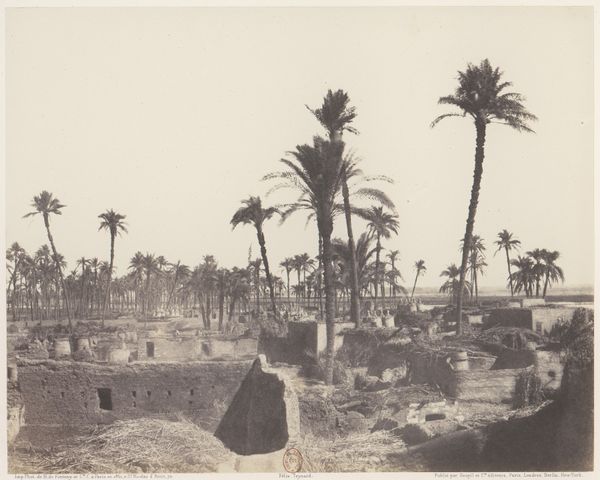

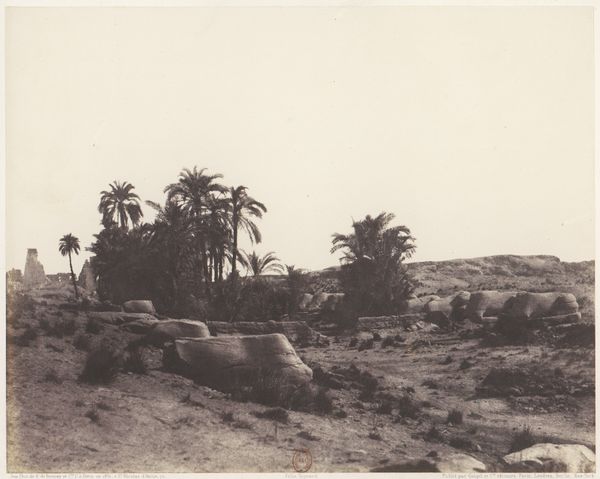

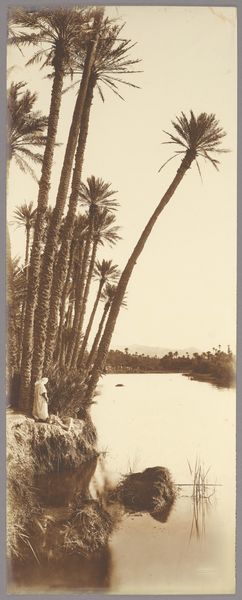

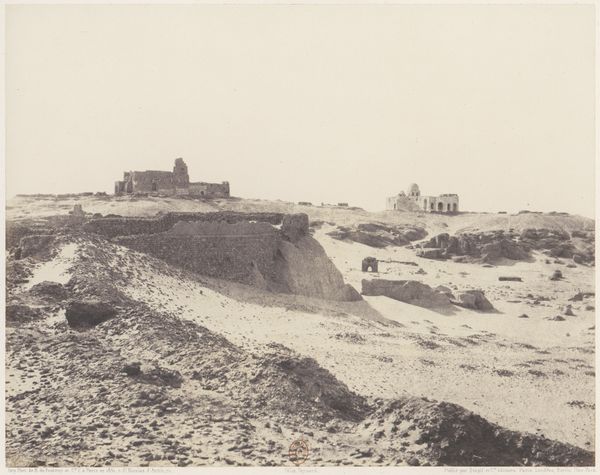

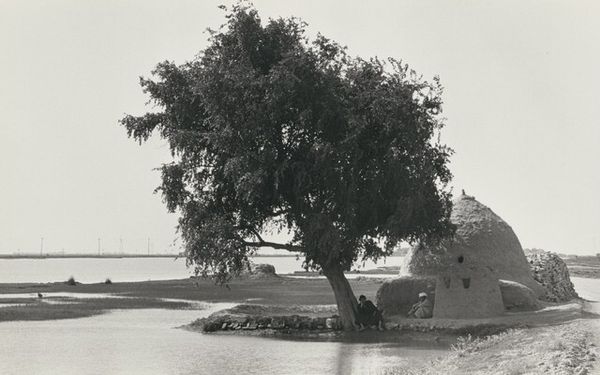

Curator: We're looking at Fèlix Teynard's "Dakkeh, Village et Rives du Nil," a daguerreotype from 1851-1852. It offers a stark, almost ethereal view of the Nile. Editor: It’s… bleached. The heavy sky seems to flatten everything beneath. Despite the clarity of the photograph, there’s a sense of overwhelming stillness, even oppression. Curator: Absolutely. Teynard was part of a French photographic expedition to document Egypt. Beyond artistic expression, these images were deeply entangled with colonial narratives, weren’t they? The act of documenting itself becomes an assertion of power. Editor: Precisely! What kind of power did the image hold? Teynard’s camera not only frames Dakkeh for a European audience, but also contributes to the colonial gaze, defining Egypt through a lens of exoticism and perhaps control. The palm trees, the ancient ruins – are they simply landscape features, or also stand as emblems of an idealized past ripe for interpretation and subjugation? Curator: The sharpness of the daguerreotype also adds another layer to consider. Think about it: these early photographs held a presumed objectivity that paintings, for example, didn't necessarily possess in the public imagination. How might viewers have received it at the time, considering what could be considered reliable proof of another place? Editor: It likely reinforced existing imperial assumptions, this idea of the "untouched" land. The technology amplified the power of representation, transforming a community and landscape into an artifact for Western consumption. It begs the question: Whose story is truly being told through this "objective" image? The history is silent of those who inhabited and cultivated Dakkeh's land and society. Curator: An important observation. Teynard's work gives us insight into the mechanics of early photographic practice, while raising urgent questions about the relationship between art, history, and political power. Editor: Indeed. Beyond the beauty of the photograph itself, we have this reflection on the systems that enable the making and distribution of such images and how their meaning and influence ripple throughout society, historically and to this very day.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.