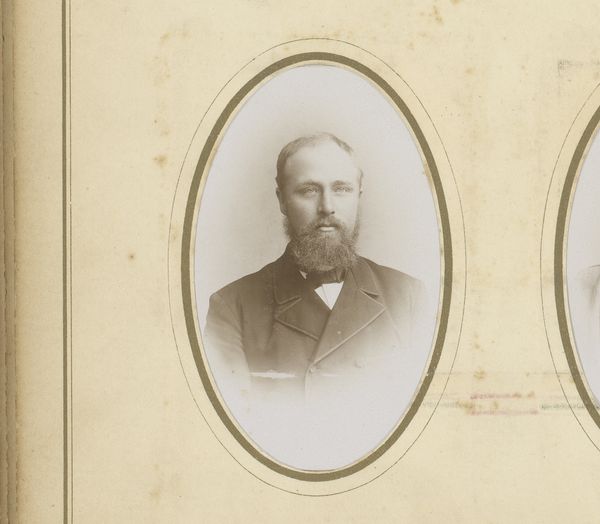

Governor Hughes, Arkansas, from "Governors, Arms, Etc." series (N133-1), issued by Duke Sons & Co. 1885 - 1892

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, watercolor, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

caricature

#

caricature

#

watercolor

#

pencil

Dimensions: Sheet: 2 9/16 × 4 5/16 in. (6.5 × 11 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

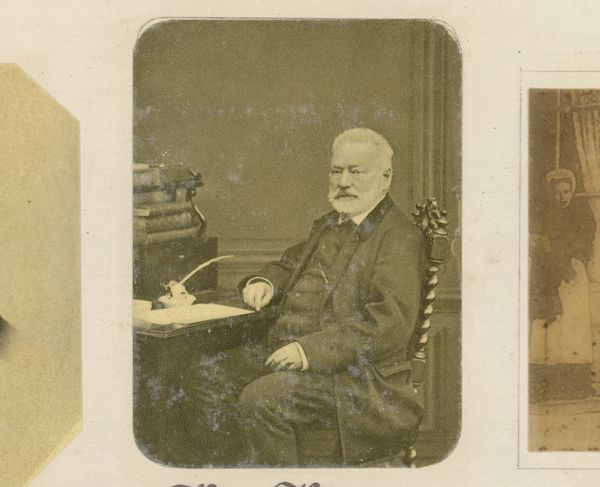

Curator: This vibrant chromolithograph presents us with “Governor Hughes, Arkansas, from 'Governors, Arms, Etc.' series," dating between 1885 and 1892. Part of a series by Duke Sons & Co., it resides here at The Met. Editor: It’s quite the tableau. My immediate impression is of the striking juxtapositions; the governor's stern visage clashes intriguingly with the colorful vignettes on either side. There's a definite sense of layering and perhaps irony. Curator: Precisely! Observe how the artist fragments Hughes into three distinct symbolic realms. On the left, Arkansas's coat of arms floats above a miniature landscape of Hot Springs. In the center, we have the governor himself, rendered with a certain unflinching directness. Finally, a Commodore’s pennant tops another Arkansas Valley scene, hinting at naval history and the commerce of Fort Smith. Editor: Right. What interests me is the inherent tension in using such commercial means - tobacco cards no less! - to portray governance. It elevates Hughes, yet the ephemerality of the card reduces the gravitas of his office. How do we reconcile the artistic and the utilitarian purposes here? Curator: It underscores the pervasive nature of consumerism. Cigarette cards like this were miniature billboards that reached a broad demographic, and including governors, state symbols, etc. legitimized and normalized this commercial venture by associating it with familiar cultural ideas. Editor: Interesting! It’s a clear attempt to merge the cultural landscape with consumer desire. And considering that these chromolithographs, employing multi-stone printing, relied on significant manual labor, the human cost is embedded directly within these images, as is the production, distribution and the means of consumption tied up into the product. Curator: Indeed, tracing its origin and production unveils a network of factors beyond Hughes’s portrait. I find that by decoding its symbolic layers and engaging in this semiotic dance, it reveals deeper cultural and societal values during the Gilded Age. Editor: Absolutely. I see it less as high art and more as a compelling visual artifact rooted deeply within industry and manufacture, yet laden with its own deliberate symbolic choices and meanings, of course. Food for thought.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.