drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

#

ink drawing

#

pen sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pencil

#

sketchbook drawing

#

genre-painting

#

sketchbook art

#

realism

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

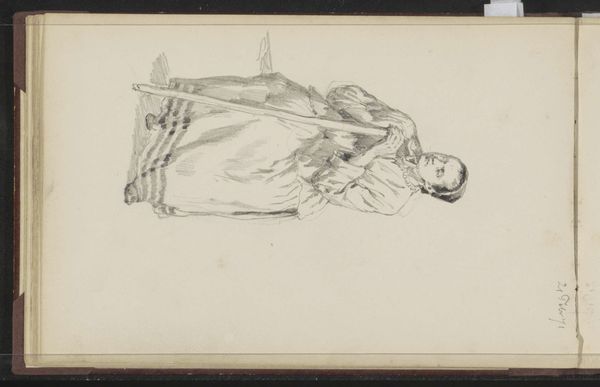

Curator: Let's take a look at this evocative sketch, "Vrouw die haar eigen pols beetpakt," or "Woman biting her own wrist," tentatively dated to 1873 and attributed to Cornelis Springer. Editor: It's a striking image. The way the artist uses pencil on toned paper creates a subdued and somewhat unsettling mood. The figure’s posture immediately conveys a sense of inner turmoil or distress. Curator: Indeed. Springer was primarily known for his architectural paintings, capturing cityscapes with precise detail. This drawing, in contrast, feels deeply personal, like a raw and immediate expression. What social dynamics do you think might be at play? What drove him to deviate to draw a piece like this? Editor: Considering the historical context, the late 19th century was a period of immense social change and shifting gender roles. Perhaps this drawing reflects anxieties surrounding female identity, and societal expectations that confined women and sometimes led to desperate acts. The wrist-biting itself can be interpreted as a symbol of self-inflicted harm, a way for women to gain a bit of freedom from control. Curator: I appreciate how you bring a contemporary lens to this work. Thinking intersectionally, we must also consider class. For women of lower socioeconomic standing, the constraints might have manifested in different forms – physical labor, lack of autonomy, different expressions of control within their families. Could it reflect mental health challenges prevalent in that era, which are often ignored? Editor: It's a valid point. Public discussions surrounding mental health were definitely stigmatized, but that does not suggest those issues were any less potent. I think an examination of asylums during the time, or even contemporary medical pamphlets may help to illuminate some socio-political considerations related to this drawing. Curator: This makes me think about the act of drawing itself – the intimacy of the artist with their subject, the almost voyeuristic peek into someone’s private moment of distress. Was this commissioned? What can the artistic conventions used in this portrait uncover about its provenance? Editor: We can be almost certain this drawing comes from a sketchbook; a pen-ink sketch could very likely mean that this was one of a series of quick poses from daily life that Springer captured in his personal notebook. Curator: It's powerful how a simple sketch can open up a complex dialogue about individual and societal pressures, still echoing through our own time. Editor: Agreed. It really shows the enduring relevance of historical art when we bring both the artist's intention and contemporary social awareness into the mix.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.