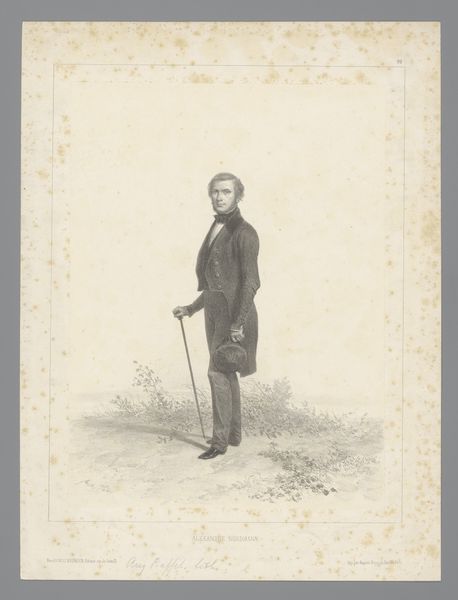

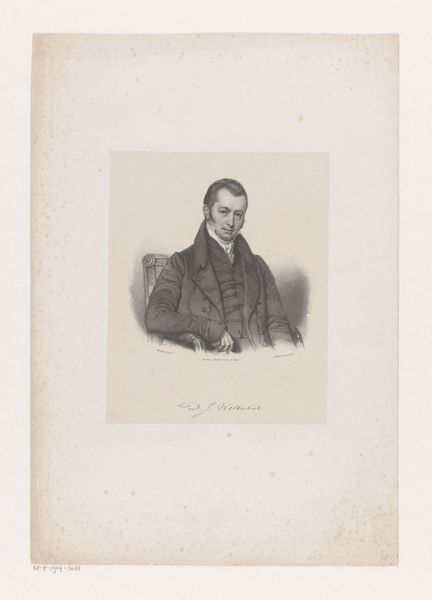

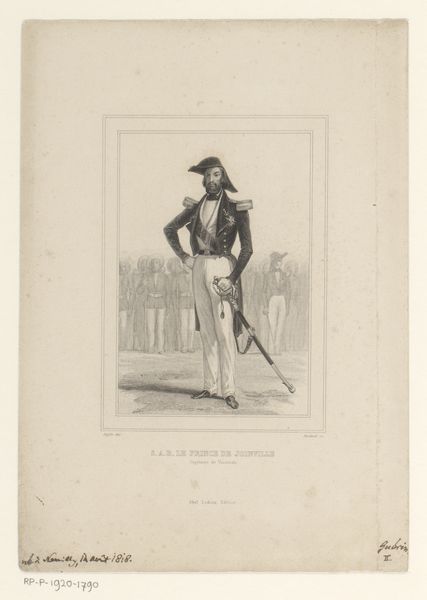

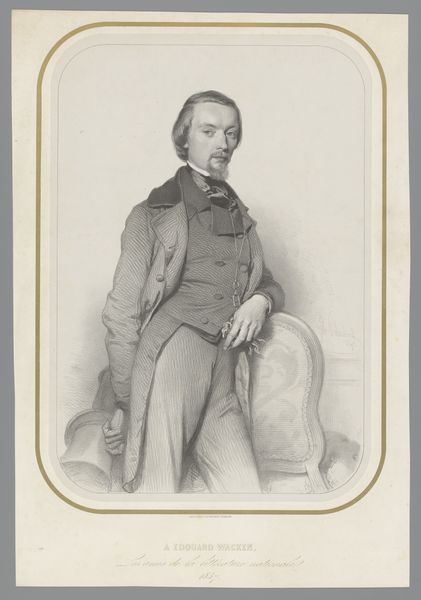

print, engraving

#

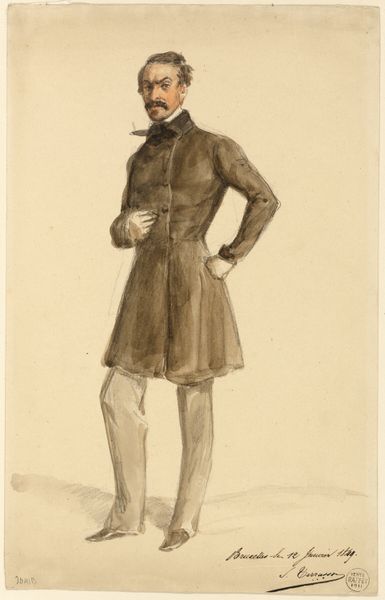

portrait

# print

#

romanticism

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 457 mm, width 315 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is Auguste Raffet's "Portrait of Paul Kolounoff", an engraving from 1848. I find the figure has an incredible sense of stillness; everything in the composition feels balanced and poised. How do you read this portrait? Curator: What strikes me first is the sitter's composed elegance, despite what must have been a turbulent time in Europe! This piece reminds me that portraiture, especially engraving, had the fascinating power to both idealize and document. He's definitely striking a pose, but the artist also manages to capture what feels like a candid quality. Don't you think there's almost a modern sensibility in his eyes? A self-awareness perhaps? Editor: That’s such an interesting take! It's as though he knows he's being observed and is presenting a specific version of himself. It is subtle. It is just…there! How does the fact that this is a print, an engraving specifically, influence your perception? Curator: Well, an engraving inherently involves a translation—the artist meticulously carving lines into a plate that's then inked. This process creates a layered, almost textural quality. You lose the immediacy of, say, a charcoal sketch, but gain an incredible precision and potential for mass production. I think Raffet masterfully uses the medium to emphasize line and form, capturing Kolounoff's presence with remarkable detail. What do you make of that, looking closely? Editor: I didn't even think of that level of exactitude that the medium demands. I just thought of ‘print’ as in… replicated…but your explanation shows that each image can hold such detail, revealing the sitter and also something about the artist who engraved the plate. I’ll definitely be stopping by prints and engravings more often. Thank you! Curator: Indeed. It’s always more rewarding once we truly look!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.