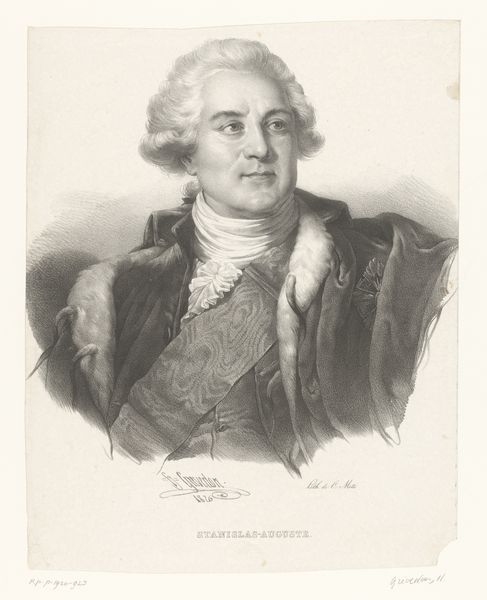

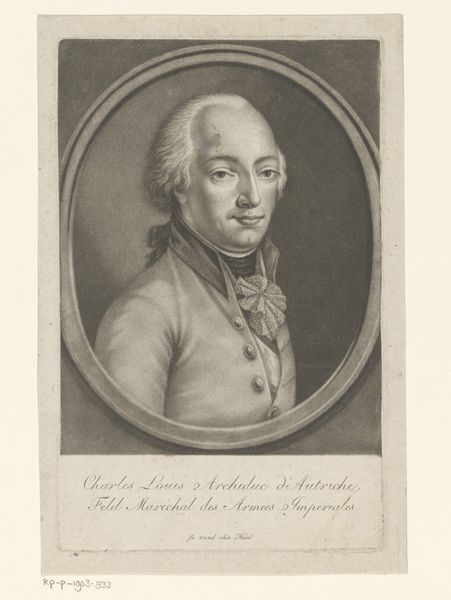

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

charcoal drawing

#

portrait reference

#

pencil drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 325 mm, width 237 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This refined portrait from sometime between 1806 and 1863 immediately evokes an air of understated dignity for me. The subject's composed expression seems to hint at a life lived in service and contemplation. Editor: The high contrast emphasizes not only his stern gaze, but the sharp social divide between those rendered in detail and those left outside the frame during that time. There's something subtly unsettling about the romanticization of power, even in what seems like a simple portrait. Curator: What do you mean, exactly? To me, this engraving by Tommaso Benedetti—currently held at the Rijksmuseum—speaks of a broader neoclassical reverence for structure and order, ideas perhaps manifested here through the precise lines. It shows Stephan Edler von Wohlleben; look at the symbols of his office, that suggest dedication to civic life, to his city’s wellbeing. Editor: Civic life—but for whom? During the early 19th century, particularly after the Napoleonic Wars, the burgeoning bourgeoisie consolidated power while much of Europe faced famine and economic crises. Stephan's portrait subtly whispers the story of that societal shift, the entrenchment of class. Even the very neoclassical structure and clean lines, to me, are symbolic of power dynamics, a desire for control amidst chaotic change. Curator: You bring an interesting lens, positioning Stephan Wohlleben within this painting, through his status. Looking at his medallion—I find the precise engraving almost meditative. It suggests that Benedetti was interested in portraying ideals as much as he was portraying a man, suggesting moral fortitude. Editor: Well, the engraving technique itself echoes themes of replication and dissemination—fitting for an era increasingly dominated by print and mass communication. While portraying moral fortitude was no doubt intentional, those are tools also used to legitimize figures that upheld specific class interests and sociopolitical values of that period. Seeing him like that almost renders Stephan into a symbol of the ruling class, intentional or not. Curator: You have certainly encouraged me to think beyond the surface—beyond what this print meant as a personal artifact—towards what it may say about its own era. Editor: And I've learned a lot from seeing the care put into making meaning. I wonder now, about all the messages hidden and not.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.