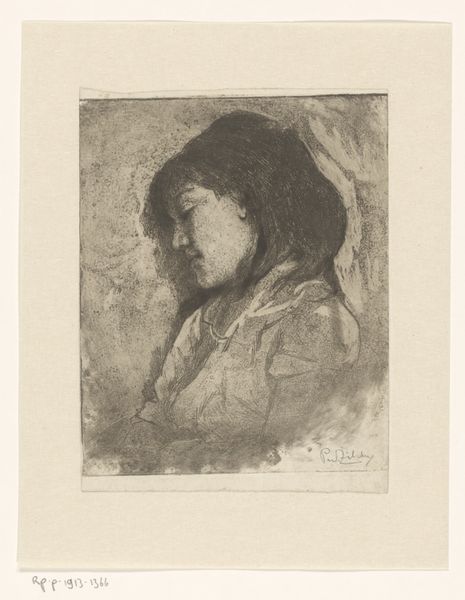

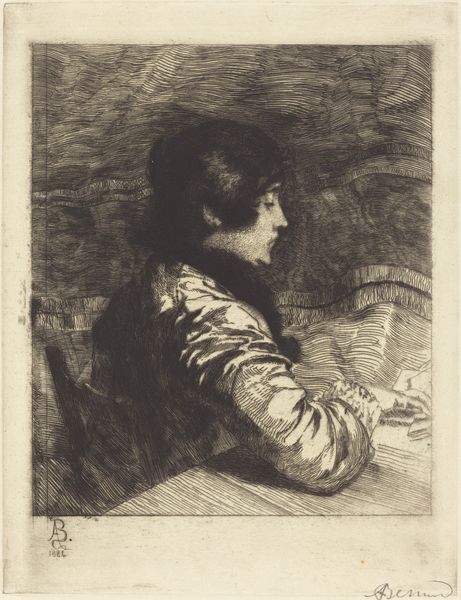

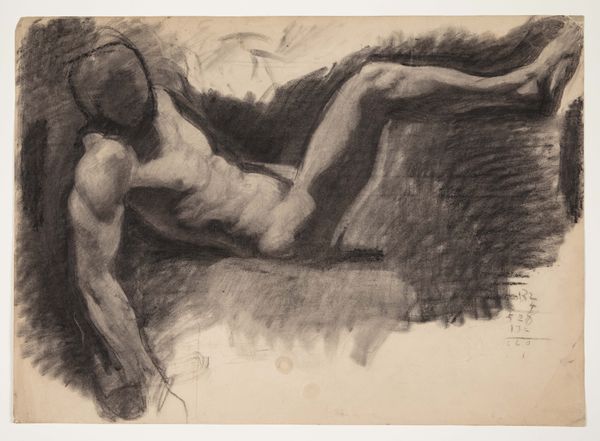

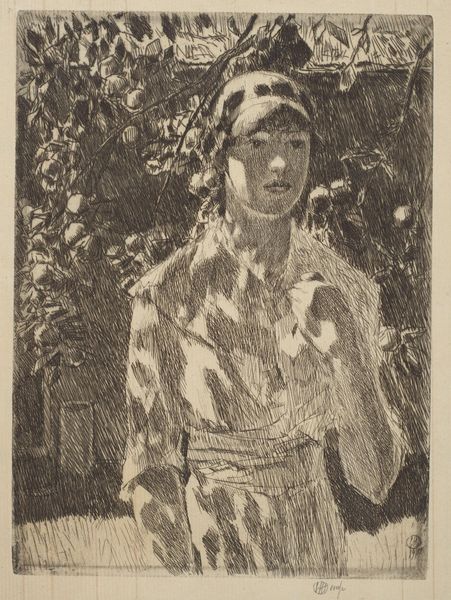

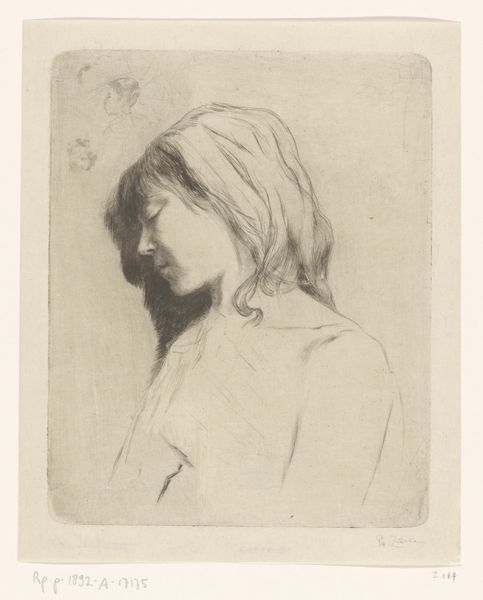

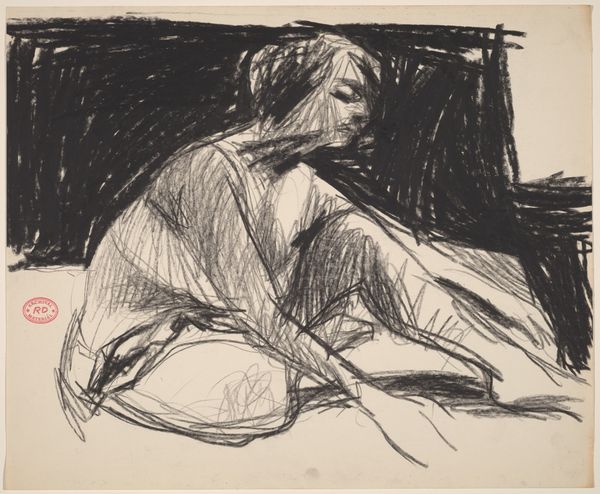

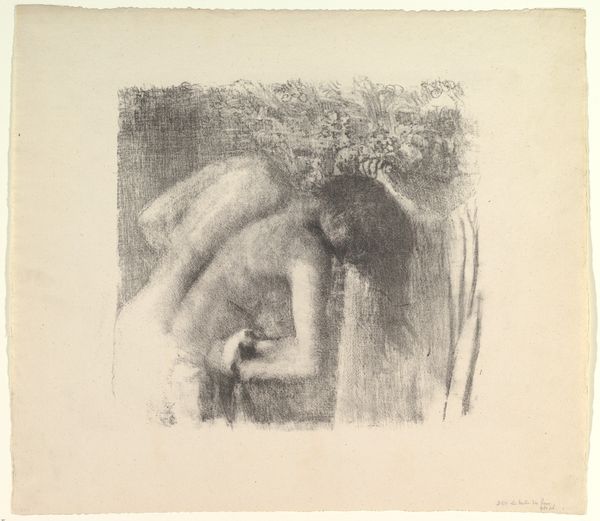

print, charcoal

#

portrait

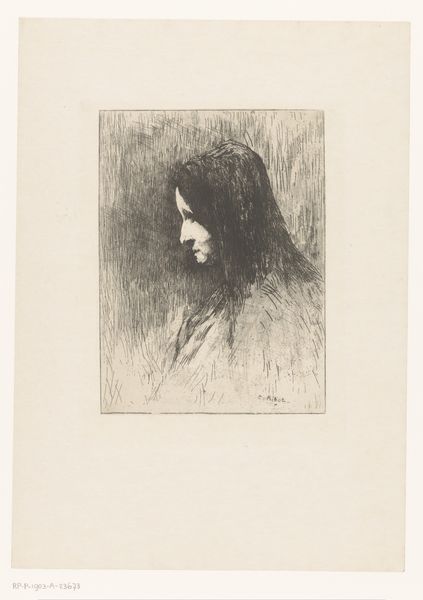

# print

#

impressionism

#

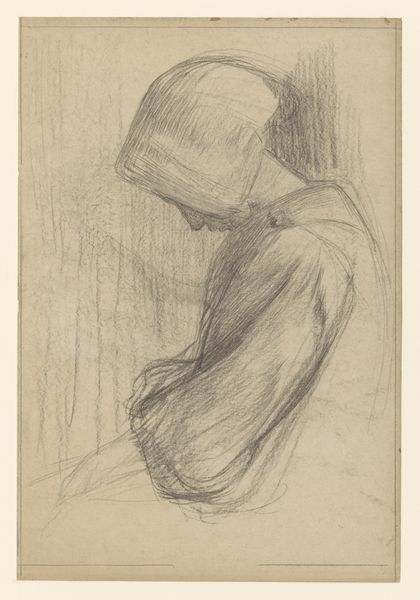

charcoal drawing

#

charcoal

#

realism

Dimensions: sheet: 31.12 × 43.34 cm (12 1/4 × 17 1/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Frank Duveneck’s “Head of a Woman,” created in 1884, offers an intimate glimpse into the aesthetic values of its time. Made with charcoal, this piece highlights the artist’s skillful handling of light and shadow. Editor: The immediate feeling I get is one of serene melancholy. The limited palette emphasizes soft contrasts and subtle shifts in texture. Her downcast gaze almost speaks of wistful reflection, doesn't it? Curator: Indeed. Duveneck, associated with the "Munich School," advocated for direct painting, valuing the artist’s immediate response to the subject. It's believed his experience studying portraiture played a role in refining the subject. Editor: Her loose hair is quite interesting; I interpret her flowing hair as freedom or a gentle protest to social norms, especially if we place her in the context of late 19th-century conventions. It subtly disrupts rigid Victorian ideals, suggesting female subjectivity. Curator: Precisely! This aligns with a broader historical movement towards artistic naturalism. There’s a conscious effort to portray an unvarnished, realistic vision of womanhood, away from conventional studio portraits with the idealised subject and staged backdrop. The charcoal medium itself adds to this intimacy, reflecting the immediacy and personal expression characteristic of Duveneck's philosophy. Editor: Considering the institutional art world, there's a contrast: his looser drawing feels almost confrontational amidst the academic precision of the day. It's as though he were capturing a moment, revealing an intimate dialogue between artist and muse. Is that what attracted collectors and his peers? Curator: It certainly resonated with a generation that was keen to champion art with visible and apparent skill. Duveneck, later in his career, gained acclaim, instructing many students as well as influencing younger painters. We must look at how that plays a crucial part in the understanding of the role of this imagery, because it was crucial for others that followed. Editor: Thank you for highlighting that context. I'm taking away that this drawing embodies so much more than the beauty of its muse—it also stands as a testament to a turning point in artistic expression and representation. Curator: I'm glad you appreciate the larger implications that shaped Duveneck’s work. Appreciating art involves seeing how aesthetics intertwine with broader historical and social forces, offering layered insights into the culture that both influenced, and was subsequently influenced, by art itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.