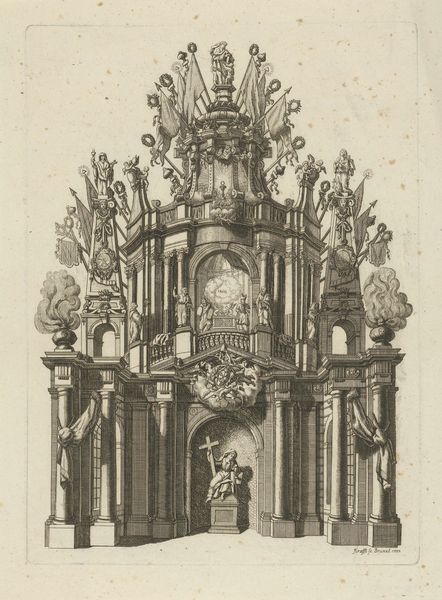

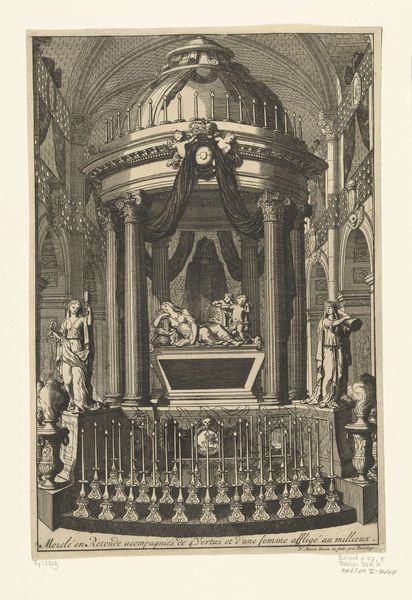

De katafalk opgericht in de Sint Gudula (plaat III onderste helft), 1622 1623

0:00

0:00

cornelisgallei

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving, architecture

#

baroque

# print

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 445 mm, width 342 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a print from 1623, titled "De katafalk opgericht in de Sint Gudula," or "The Catafalque erected in Saint Gudula," created by Cornelis Galle I, and held in the Rijksmuseum collection. What strikes you most about this work? Editor: Immediately, the architecture, the ornamentation, and the intricate detail suggest a space charged with ritual, or the performance of power. It looks immense even on this small scale! Curator: Absolutely. It's a fascinating piece, capturing a specific historical moment, the erection of a catafalque, an elaborate structure built to honor the dead within the context of Saint Gudula. Consider the sociopolitical significance. Who was being mourned here, and what did such a spectacle communicate about the distribution of power at the time? Editor: It makes me consider the labor involved in such an ephemeral structure. The skilled craftsmen who designed and constructed this, and the raw materials used, however temporary. There is social value embedded in the work—skilled work for those elite patrons. Curator: Precisely. And beyond just a snapshot of skilled tradespeople at work, look at how Baroque theatricality operates as a tool for ideological messaging. What statements are made via the architecture shown here and via the presence of these figures? Editor: The very *act* of creating and presenting the engraving becomes part of that messaging, doesn’t it? The act of memorialization, reproduced and circulated. This printed version, produced in multiples, then amplifies the scale of it. Curator: A fantastic point, as the print would become a material representation of grief, circulating ideas and social hierarchies further. And don't overlook that it functions both as historical record and propaganda, reflecting the power dynamics between church and state. The performative aspects become particularly charged when we think about Baroque sensibilities, wherein performance, architecture and symbolism blend so dramatically. Editor: Yes! By carefully considering how it was made and then used, what materials went into it, and by whom it was disseminated we get much closer to understanding the social life of the piece, not just as aesthetic exercise but also as part of the everyday political life of its period. Curator: It’s powerful to consider the socio-political implications and lasting influence this piece of architecture would hold, specifically, around notions of religion, status, and memory. Editor: Exactly. Thinking of its production brings a vital connection with the time and society that saw fit to produce it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.