print, woodblock-print

#

portrait

# print

#

asian-art

#

ukiyo-e

#

figuration

#

woodblock-print

#

genre-painting

Copyright: Public domain

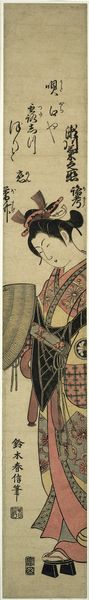

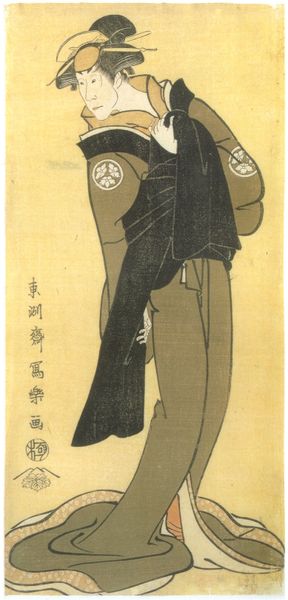

Curator: Welcome. Here we see "Sanokawa Ichimatsu III as Sekinoto, wife of Fuwa Benzaemon," a striking woodblock print created by Tōshūsai Sharaku in 1794. Editor: The monochrome aesthetic lends a gravitas that the details fight against. I can't quite tell what kind of story this portrait is trying to tell! Curator: The artist, Sharaku, produced prints for only about ten months. But in that time, he focused on portraying kabuki actors, often in roles that subverted traditional expectations. Notice the repetition of the design printed on the kimono sleeves. Editor: You’re right to point that out. There is a fascinating duality here; on the one hand, you have the overt, surface-level image of status, power, even luxury signaled by the complex fabrics—the production of these objects required skilled labor and specialized resources. Yet there is something very sad in this figure's posture. The downturned glance seems laden with hidden meaning. Curator: It's essential to recognize how the Ukiyo-e tradition, although depicting the floating world, was grounded in the socioeconomic realities of Edo-period Japan. Sharaku’s focus on capturing likeness – sometimes unflatteringly so – disrupted the norms of idealized beauty. And note how the background itself isn't pristine. We see a bit of the raw material itself, not hidden from view. Editor: Absolutely. Kabuki itself was a space for challenging social hierarchies. These actors—often from marginalized communities—gained immense popularity and challenged the established order through performance. So, how might this particular portrayal reflect Sharaku’s and perhaps the audience’s perspective on gender roles, on women’s social positions at the time? Does the wife of Fuwa Benzaemon even have the agency to challenge expectations, or is her representation solely defined by male expectation? Curator: We should also think about distribution and consumption of these prints. They were produced relatively quickly and sold to a broad urban audience. Think of the artisans, the printers, and publishers involved, creating a visual language available across different social classes. Editor: It makes me think about access—who gets to be represented, how, and why? This artwork really allows us to grapple with the tensions between individual expression and broader social and political narratives, doesn't it? Curator: Indeed. It is a testament to how deeply intertwined artistic expression is with material conditions and social commentary. Editor: Right. Sharaku provides just a small, compelling window into a world we must view with our own contemporary analysis.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.