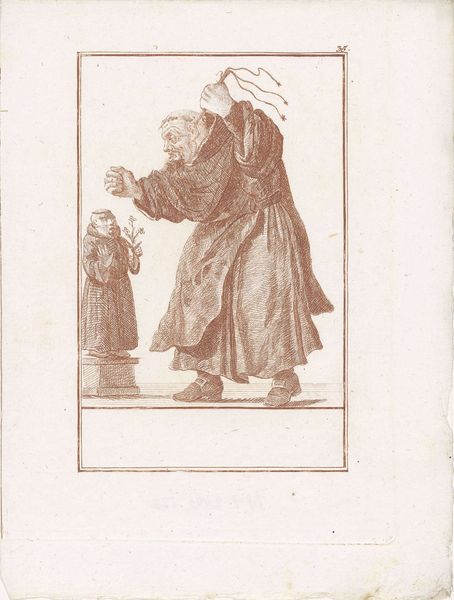

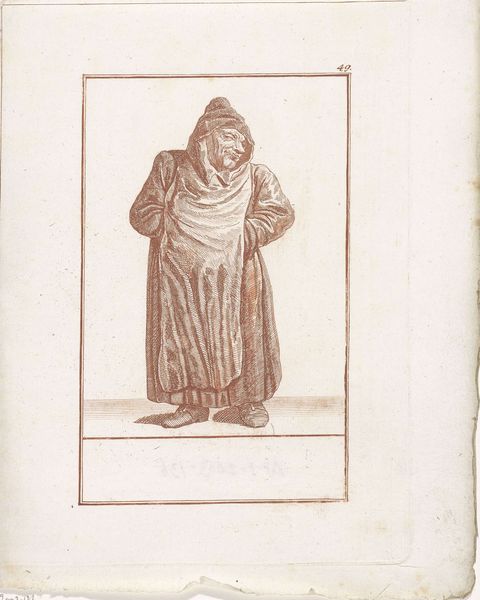

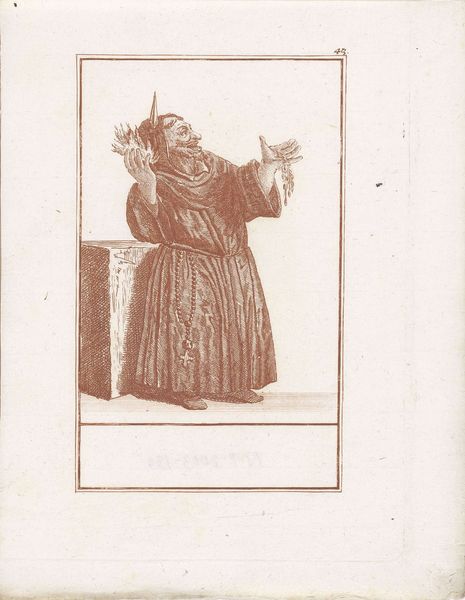

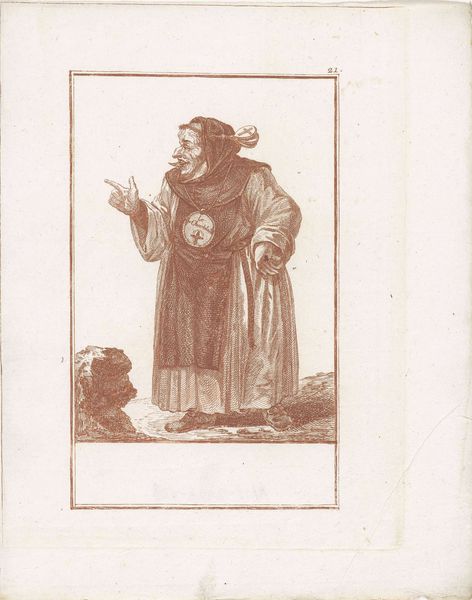

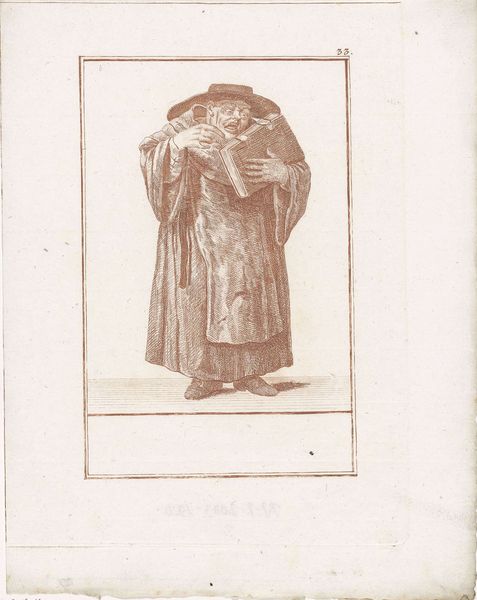

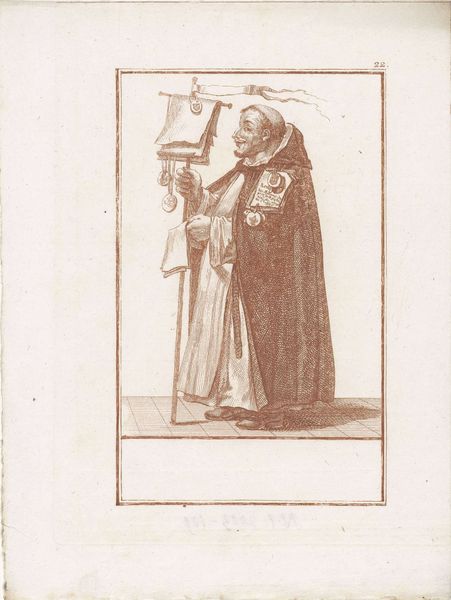

engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

figuration

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 235 mm, width 183 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This engraving, "Monnik en twee cherubijntjes" made in 1724 by Jacob Gole and held at the Rijksmuseum, feels so meticulously crafted. I’m really struck by how the lines create texture, especially in the monk's robes. What draws your eye to this piece? Curator: It’s the labor embedded within those very lines that captivates me. Consider the engraver’s meticulous process, the physical act of cutting into the copper plate, each stroke demanding precision and control. How might the conditions of Gole's workshop, the availability of materials, the demands of the market, have impacted the final form? Editor: That's fascinating, I hadn't thought about the actual labor so directly. Does the material – the copper plate, the ink – have any symbolic meaning here? Curator: Absolutely! Think about the value of copper itself. It was a commodity, a material resource. And engravings? They were a form of mass production, making images accessible to a wider audience beyond the elite. It challenges the aura of the unique artwork. It speaks to a shift in consumption, doesn't it? Was this image devotional, decorative, or something else entirely? Editor: I see what you mean. It's less about the monk's spiritual experience and more about how that image was produced, distributed, and consumed within a specific social context. I suppose that cheap dissemination challenges high art? Curator: Precisely. And think of the implications! The "original" becomes less important than its reproductions, democratizing the image and questioning traditional notions of artistic value and ownership. Editor: So much to think about beyond the initial image. It makes me reconsider what 'art' really is. Curator: Indeed. By focusing on the materials and methods, we unveil a whole world of social and economic relations embedded within this seemingly simple engraving.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.