Copyright: Public domain

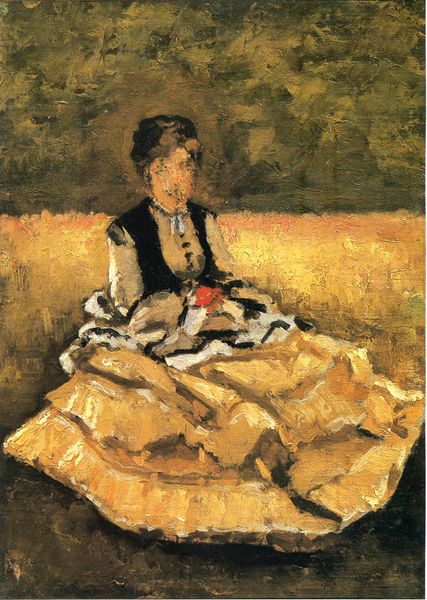

Curator: The contemplative gaze of this sitter is arresting. Editor: It has a somber tone, almost melancholy; is she looking inwards, or at a future out of reach? Curator: What you are experiencing is echoed in the symbols throughout Arnold Böcklin’s oil painting, "Portrait of Clara Böcklin," executed in 1872. Beyond just being his wife, Clara functioned as one of Böcklin's frequent models, representing his allegorical figures. Editor: It’s a relatively small-scale piece, isn’t it? It creates this intimate sense of witnessing a private moment. There’s this dark vase near her by the window, contrasting starkly against the light in her white dress. It’s such a vivid depiction of internalized domesticity, but is she content, or trapped, in this space? Curator: Böcklin was greatly inspired by Romanticism and it's turn toward personal emotions; domestic settings have an iconography all their own. The vase, the light from the window--it suggests a tension between stillness and movement, interior life, and the beckoning world. It all communicates a profound psychological landscape, which the artist, with his selection of those symbolic motifs, wants to explore. Editor: But who decides what's romantic, and what's not? Böcklin presents his sitter framed in stillness as if, by aestheticizing his domestic portraiture, he might fix and perhaps, control, not only the figure, but by extension, perhaps also Clara's subjectivities. Does that mean women lose agency even when artists love them? Curator: Perhaps that's reading it too literally? Clara embodies themes. You can detect realism, certainly, but even then, the red bow in her hair, in a context of subdued lighting and earthy greens, creates visual echoes, connecting personal symbols through form and color. We must grant some artistic license! Editor: Art IS political. And as we revisit even the most intimate portraits of the past, the sociohistorical analysis becomes essential in our appreciation, no? It might not diminish the romantic appeal of Clara as a 'muse,' but instead add complexity by viewing women's positionality in that period. Curator: Indeed, by focusing solely on iconography we risk ignoring how history colors the artist’s and sitter’s decisions. That dialogue makes the work alive and ever more intriguing. Editor: And forces us to really examine how symbols create a cultural record over time!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.