drawing, paper, ink-on-paper, ink

#

drawing

#

pen sketch

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

paper

#

ink-on-paper

#

ink

#

geometric

#

orientalism

#

line

#

academic-art

#

calligraphy

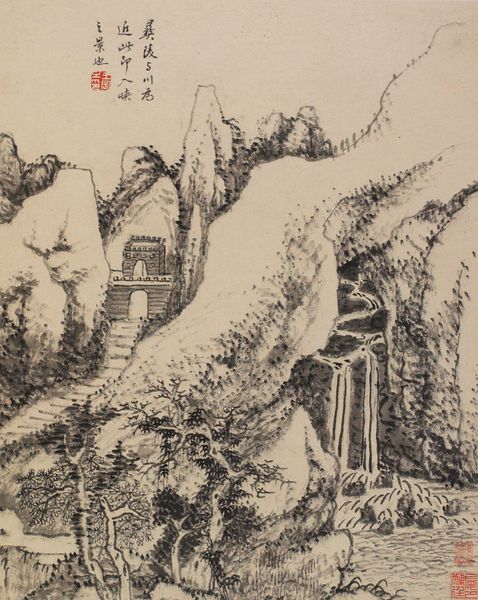

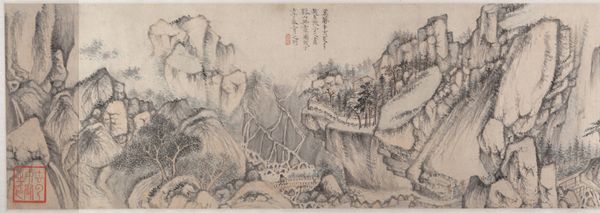

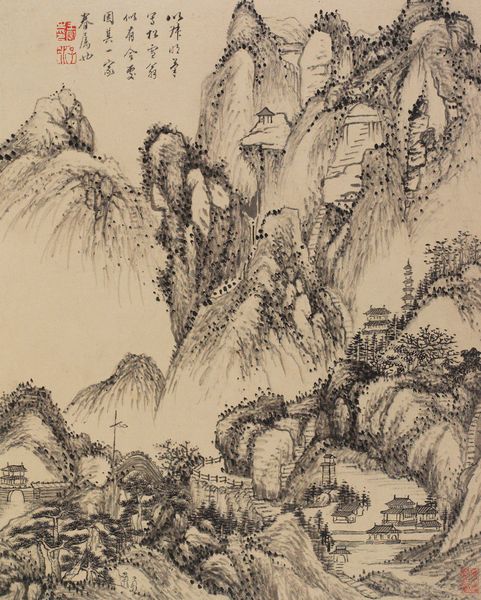

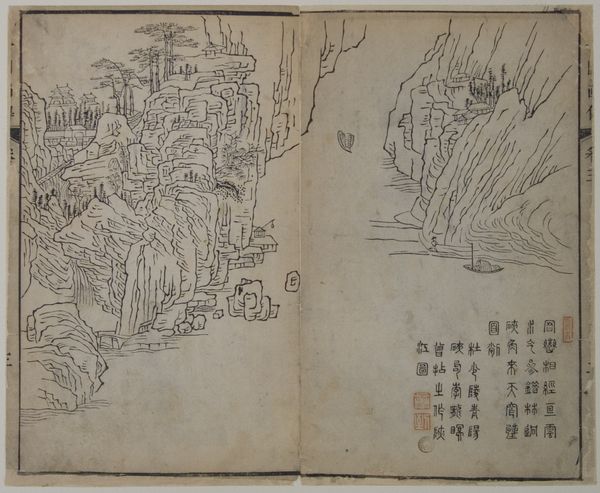

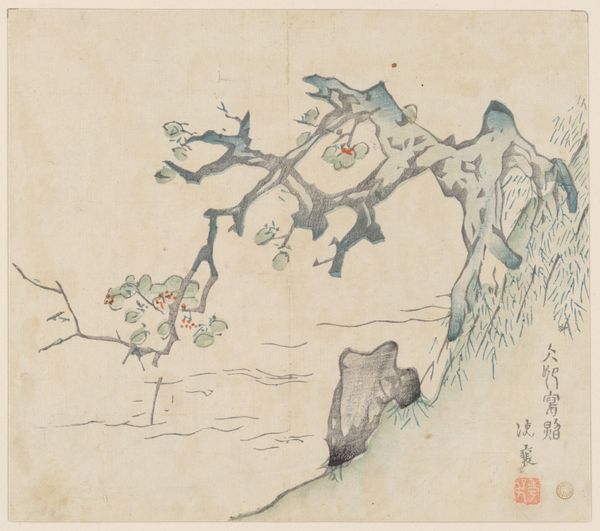

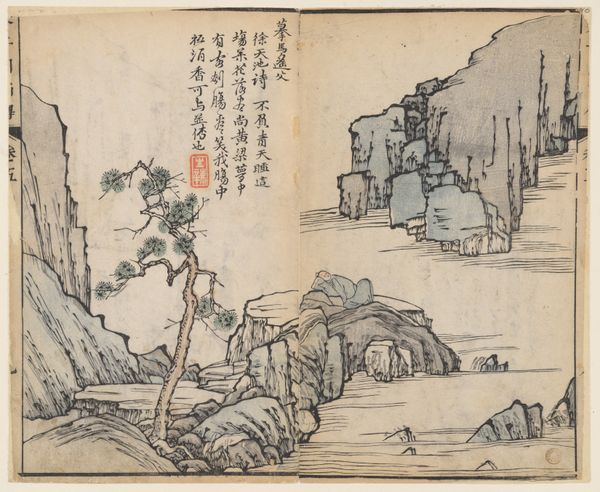

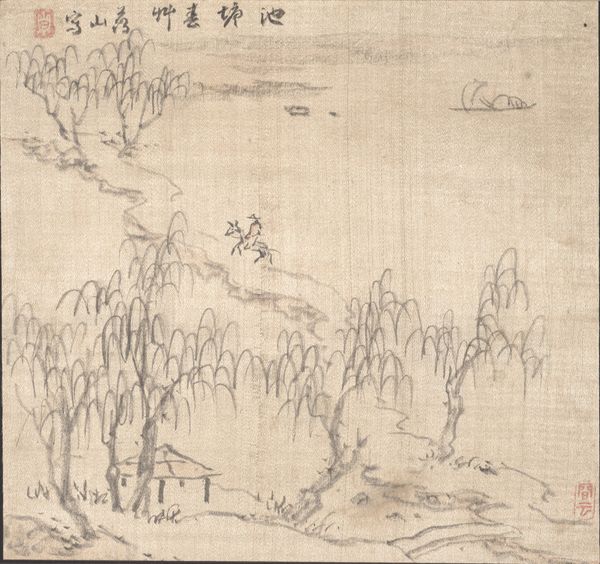

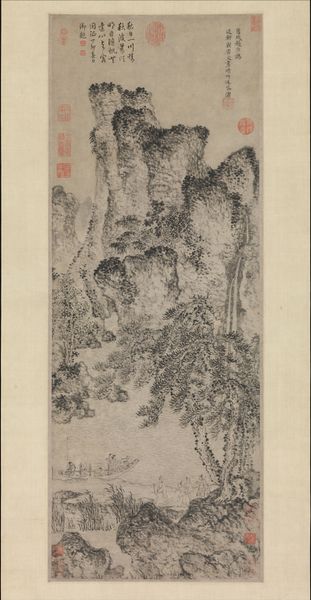

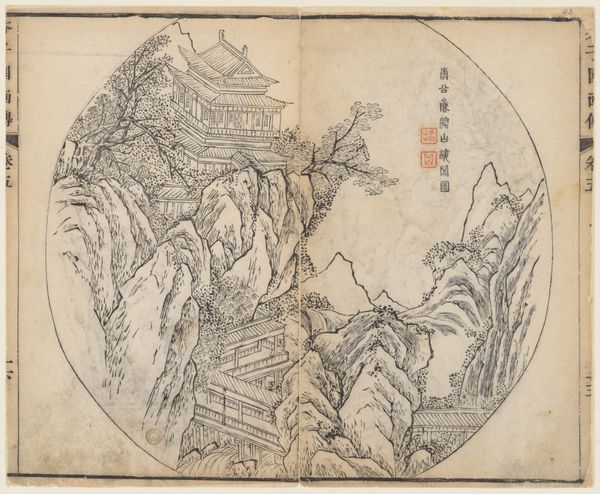

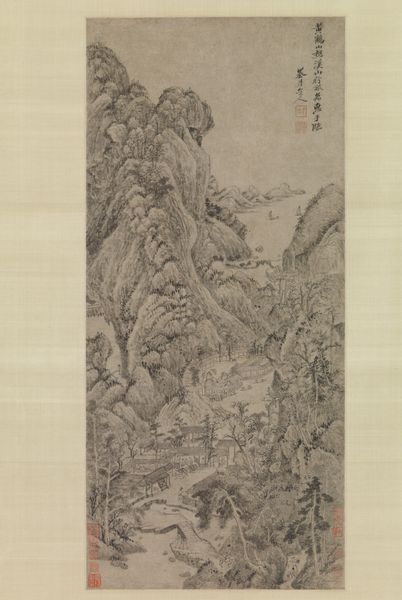

Dimensions: 16 7/16 x 13 3/16 in. (41.75 x 33.5 cm) (image)19 3/4 x 15 5/16 in. (50.17 x 38.89 cm) (leaf, overall)19 15/16 x 15 15/16 x 1 1/4 in. (50.6 x 40.5 x 3.2 cm) (entire album, overall, closed)

Copyright: Public Domain

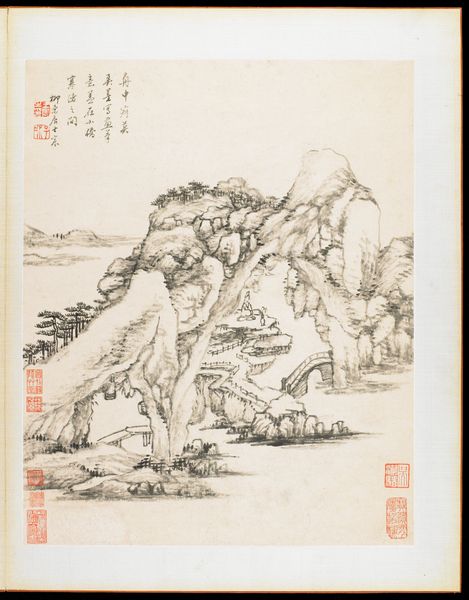

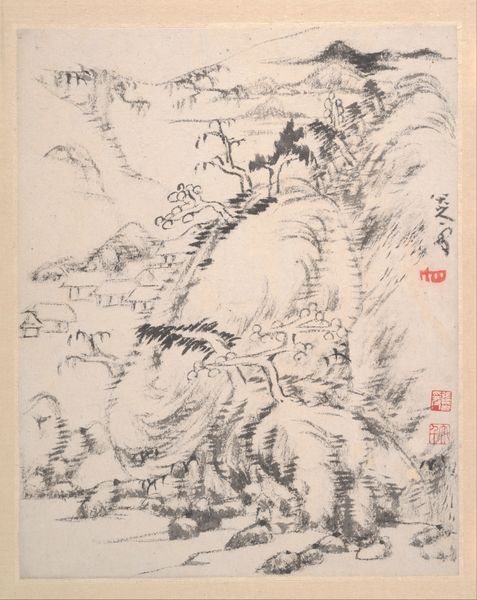

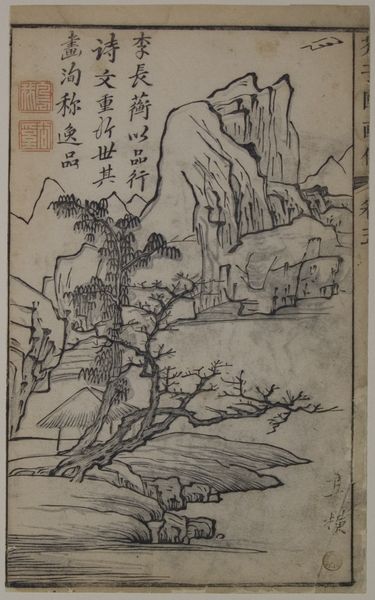

Curator: Wang Chen, working in the 18th century, presents us with "Album Leaf," created in 1774, using ink on paper. The artwork now resides here at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. What's your first impression? Editor: It feels… monolithic. Even with the delicate lines, the landscape presents an undeniable sense of permanence. The rocks feel impossibly heavy, like they’ve always been and always will be. Curator: Indeed. This ink drawing employs a limited tonal range, characteristic of literati painting. See how the rock formations aren’t just rocks? They're visual metaphors, resonating with the ancient Chinese reverence for nature and the symbolism of mountains as representing the Emperor's power. Editor: So, this isn't just a serene landscape; it's imbued with social and political undertones. The emperor's steadfast rule, rendered through an almost overwhelming natural scene. I wonder how someone viewing this at the time might react, knowing their place in such a fixed hierarchy. Curator: It goes beyond power, it represents cosmic order. Look at how Wang Chen arranges the forms. Each shape balances the next, symbolizing harmony, perhaps hinting at Daoist principles integrated into Confucian governance. There’s a connection between man and nature, emperor and subject. Editor: The mountain itself becomes a character in a narrative of social control. Considering how vulnerable land and nature continue to be due to unchecked development, the reverence communicated feels tinged with irony today. It’s almost like an elegy. Curator: I see it as a potent reminder. This work illustrates how humans project meaning onto nature to legitimize their cultural norms. While there are contemporary issues to recognize, it prompts reflection on cultural continuity and visual tradition. Editor: I still can't shake the weight of those rocks. All that mass, meant to communicate stability, seems like a precarious balancing act instead. Thanks for bringing it all to light! Curator: The past is never really past, and the dialogue continues. The symbolism evolves.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart almost 2 years ago

⋮

Born in Kiangsu province, Wang Ch'en was a descendant of the great literatus Wang Shih-min and a great grandson of the artist Wang Yuan-ch'i. He served for a while in the Grand Secretariat and as a prefect in Hunan province. Wang's illustrious family heritage strengthened his reputation as an orthodox painter and he is one of the so-called Four Minor Wangs of the later Ch'ing. Wang's inscriptions here indicate that the basis for this album of large landscapes was the natural scenery of Ch'u, a Warring States (480-221 BCE) kingdom located south of the Yangtze River. In 1774, Wang was serving as a low-level official in this region. His inscriptions also mention earlier poets and painters whose conceptual and stylistic influences along with natural scenery inspired the various scenes here, which were based on sketches made at the sites themselves. The inscriptions read: 1) The landscape of Ch'u is extremely scenic. I came across one place and sketched it but neglected to ask its name.2) One morning I entered the sea in search of Li Po; looking in vain among the paintings of mere mortals for the "Immortal of Ink." 3) The ceremonial burial mounds and Szechuan are neat. This is a scene of entering the gorge. 4) I have used the brushwork of Shu-ming (Wang Meng) to paint the style of Old Man Sung-hsueh (Chao Meng-fu). There is resemblance because they are from the same family.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.