photography

#

still-life-photography

#

pictorialism

#

landscape

#

photography

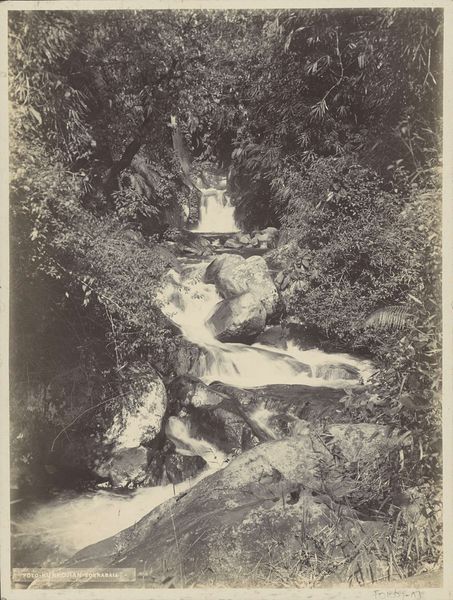

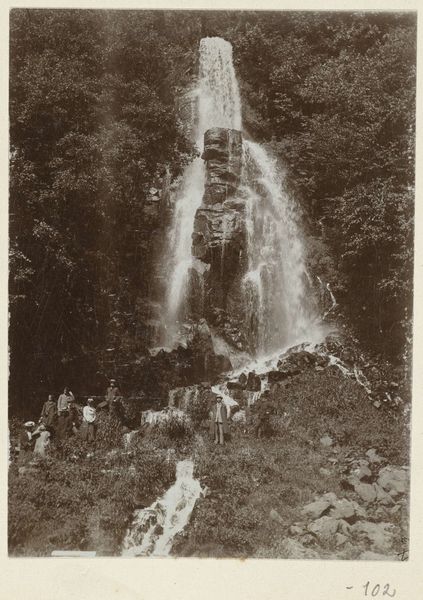

Dimensions: height 110 mm, width 81 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

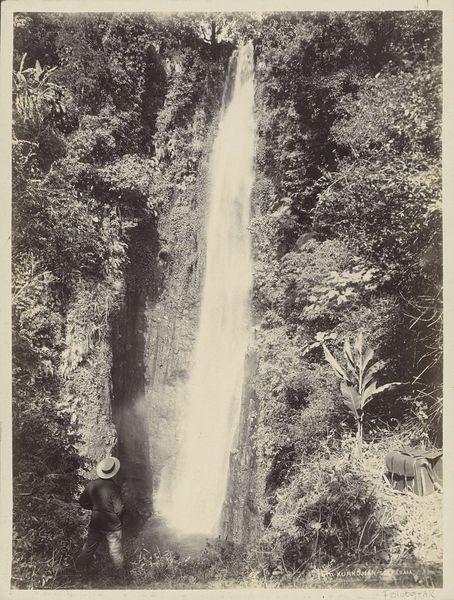

Editor: So, this is Hendrik Doijer’s "Voet waterval Montanamijn," a photograph taken sometime between 1903 and 1910. It's strikingly detailed for the period, almost dreamlike. What strikes you most when you look at it? Curator: The waterfall is obviously central. But the human figures near the base become almost totemic, markers of scale. Are they explorers, laborers, or merely placed there for sentimental reasons? That positioning asks a profound question about humanity's place in the sublime. What visual cues point you towards a potential reading? Editor: The dark foliage framing the falls certainly adds to the dramatic effect and possibly hints at hidden dangers in the untouched jungle? Curator: Precisely! Note how the water appears almost luminescent. Water is, symbolically, transformation, cleansing, but also oblivion. How does its prominence contrast against the darkness to your eye? Does the composition conjure a specific memory, dream, or place in your experience? Editor: I do feel as if I am observing the natural world through a colonial gaze. It evokes in me the tension between exploration and exploitation of natural resources. Curator: An astute point, the pictorialist aesthetic, meant to evoke painting, in this context hints to romanticize or even soften an inherently imbalanced relationship with nature. Consider the word ‘mine’ in the work’s title... Where does our attraction to picturesque nature scenes end and resource consumption begin? How do these contrasting emotions intertwine in your memory? Editor: That makes perfect sense. I guess it’s a potent reminder that even seemingly innocent images can carry complex cultural baggage. Curator: Indeed. Visual traditions rarely exist in a vacuum. Decoding them requires asking about how and why meaning persists, or alters over time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.