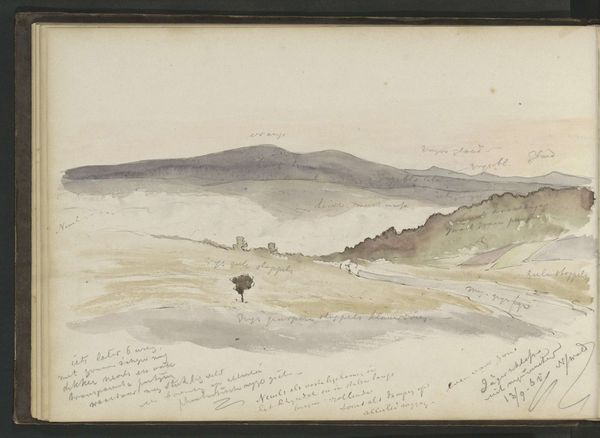

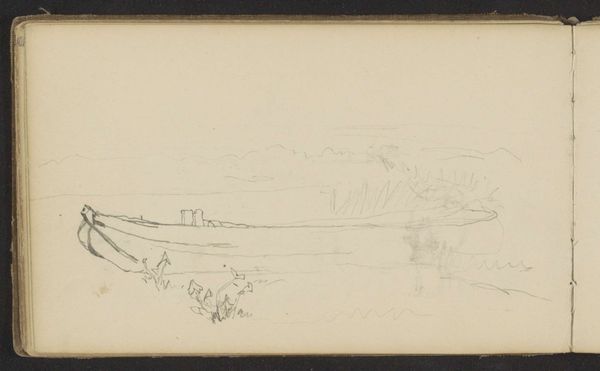

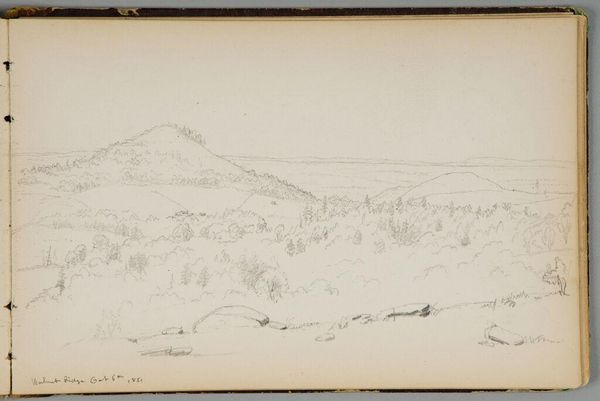

Uitzicht over het berglandschap in Niederwald met de kasteelruïne Rossel 1861 - 1869

0:00

0:00

johannestavenraat

Rijksmuseum

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is Johannes Tavenraat's "Uitzicht over het berglandschap in Niederwald met de kasteelruïne Rossel," made between 1861 and 1869 using ink and watercolor. It feels very subtle and subdued, almost dreamlike. What strikes you about it? Curator: The layering of landscape and the ruins point to a yearning for simpler times that was present in much of nineteenth-century European art, particularly landscape. It can feel passive, this longing for the past, but for me this vista evokes a certain disquiet. How might we interpret the artist’s choice to depict a ruined castle set against the backdrop of a seemingly untouched nature? Editor: Maybe it's about the relationship between nature and the man-made world? Curator: Exactly. We need to look at the context. In the 1860s, Europe was undergoing rapid industrialization and political upheaval. Artists often grappled with these changes, sometimes embracing progress, sometimes idealizing a pre-industrial past, sometimes doing both at once. I am drawn to the melancholic and subtly unsettling tones in this drawing and the quiet questioning of what "progress" means in practice. Tavenraat presents us not with an idealized landscape of proud construction, but an image of a landscape and architectural space both impacted by time. What statement is he making by doing that? Editor: That makes me consider the quiet resistance this artwork could offer. Curator: Precisely. Art doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Even the seemingly apolitical genre of landscape painting engaged with very real social and philosophical questions. It seems Tavenraat’s watercolors provide an emotional experience that evokes many of these contradictions of his moment in time. Editor: I hadn't considered it that way. It really gives me a fresh view on landscape art in general. Thanks. Curator: My pleasure. It’s by engaging with those tensions that we learn to look deeper.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.