Copyright: Public domain

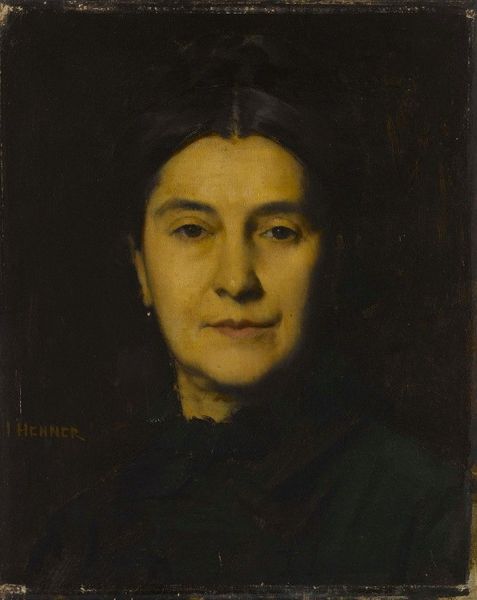

Curator: What strikes you first about Joseph DeCamp's "Portrait of a Lady" from 1908? Editor: Its understated elegance. There's a quiet strength in her profile. It feels like a very self-possessed representation. Curator: DeCamp was known for his skillful use of oil paint and his approach to portraying his subjects, capturing something of their inner life through exterior appearances. The brushstrokes are almost imperceptible, prioritizing a seamless rendering of form. Do you think this enhances or detracts from our ability to interpret her socio-economic context? Editor: It's both, I think. That seamlessness does evoke the idealized images prevalent during the turn of the century, which were frequently associated with bourgeois sensibilities and aspirations of social mobility. The subdued palette speaks of refinement, but simultaneously masks the labor conditions inherent in producing those aesthetic standards of beauty and dignity, doesn't it? Curator: Precisely. He captures this idea through surface texture, though. If we examine the layers of pigment closely, we discern the artist's hand working towards a level of naturalism which at that time indicated craft skill. It’s not photorealism. I find his conscious decisions about finish interesting because the smooth surface doesn't erase the physical actions of production. Editor: Yes, that's a helpful counterpoint. I suppose that very tension—the desire for an ideal coupled with visible material intervention—speaks to the era's contradictions as they sought a synthesis between traditional hierarchies and new forms of production. DeCamp captures something significant about early twentieth-century American ideals regarding femininity. Curator: I agree entirely. Considering both the materials and methods, the final product is intriguing in its presentation. Editor: Ultimately, DeCamp leaves us with questions about not only his sitter's identity, but what visual values mattered in a quickly changing American society. Curator: Precisely, which highlights how the portrait transcends mere representation, opening up historical dialogues that echo even now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.