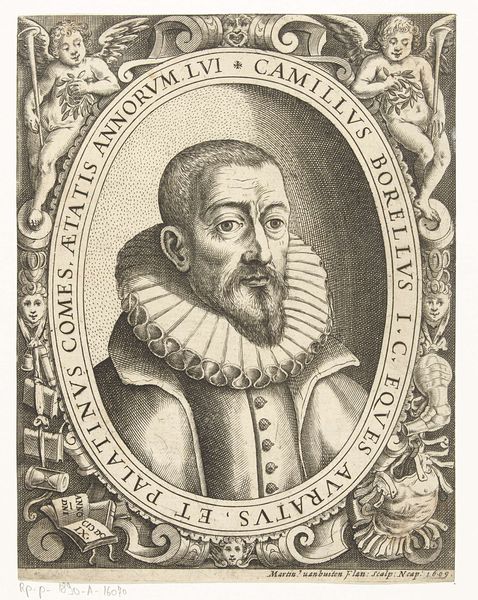

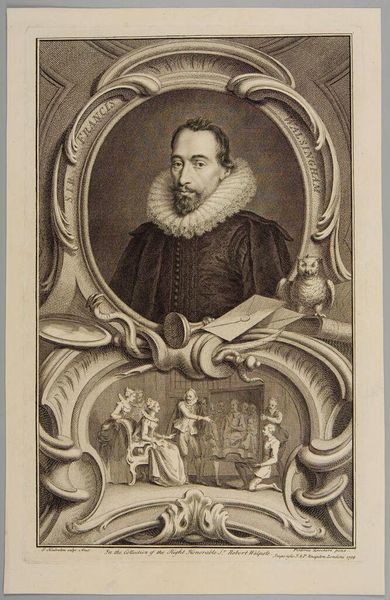

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

pen-ink sketch

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 290 mm, width 183 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let’s consider this 1631 engraving by Cornelis Galle I, currently housed in the Rijksmuseum. It's entitled "Portret van Johannes Deckher van Valckenburgh." Editor: Intricate! At first glance, the overwhelming ornamentation makes it difficult to immediately grasp the subject, but that's balanced by the stark monochrome presentation. Curator: Indeed, the framing devices command considerable visual attention. Galle presents Deckher, framed in a swirling oval, bracketed by cherubic figures, and crowned with allegorical representations of Justice and Triumph. But what is most impressive here, surely, is the graphic fidelity and delicate modeling of light given that this work is a print. Consider the details: Deckher’s elaborately pleated ruff collar against the solemnity of his gaze. Editor: Agreed. Looking at this print through the lens of societal influence, this isn't just a portrait; it’s a statement about status and power. Note how the allegorical figures are positioned— they serve as symbols of Deckher’s perceived virtues and accomplishments, solidifying his public image within the socio-political landscape of his time. This was an era deeply invested in appearances, and portraits served to uphold the social order. Curator: Undoubtedly. However, I find the graphic execution particularly compelling. Look at the contrast Galle achieves between the highly worked areas—like the face and collar—and the relatively unadorned expanse of the cloak, where one can focus instead on compositional balance. Editor: Speaking of balance, it is intriguing how the visual weight is distributed. Despite the detail concentrated above and below the portrait, the symmetry almost gives equal prominence to both the individual and the social structure they occupy. Think about the very public nature of prints: it was vital for conveying messages to the people and solidifying a patron’s image in popular culture. Curator: Precisely! The inscription is integral to the piece’s effect, anchoring meaning. It suggests both personal connection and an ambition for everlasting legacy – an aspiration common amongst patrons. Editor: This certainly complicates matters; between legacy building and artistic construction there seems a tension about its intended viewership. It seems prints, beyond simple likenesses, become crucial pieces in understanding not only a patron but the very fabric of their society. Curator: Well said. Reflecting upon this work and its place within art history deepens our grasp of this period and its rich symbolic language. Editor: Agreed. And to understand these complexities certainly adds another layer of understanding how early modern Europeans constructed their self image and the world.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.