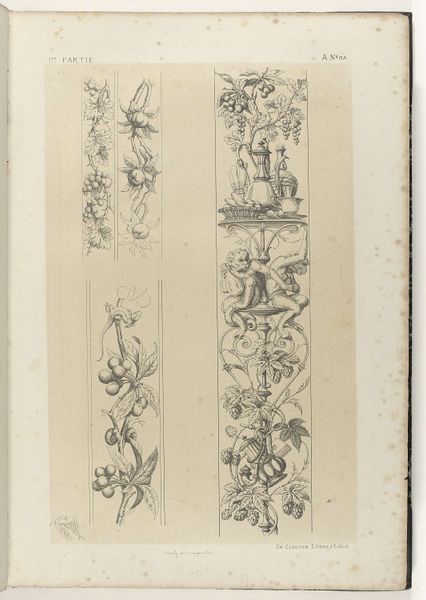

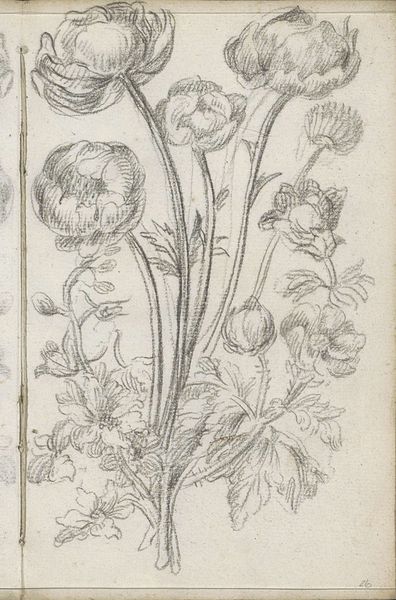

drawing, paper, pencil

#

drawing

#

paper

#

11_renaissance

#

pencil

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Upon viewing this subtle drawing titled "Boeket met bloemen," created sometime between 1710 and 1772 by Petrus Johannes van Reysschoot, I'm struck by its delicacy. It feels quite ephemeral. Editor: It’s an interesting choice to showcase a piece that feels more like a preparatory sketch than a finished work. You can practically feel the artist experimenting with line and composition. There’s something fragile and almost ghostly about its presence on paper. Curator: Precisely. And it's on paper, utilizing both pencil and drawing techniques to capture the essence of these flowers. The Renaissance fascination with nature and natural forms is very much at play. Van Reysschoot probably wasn’t creating just an innocent depiction; he participated in the cultural moment, using flower imagery that could reflect wealth, status, or complex religious symbolism, making it far more meaningful. Editor: Absolutely. The choice of flowers themselves probably had cultural significance that resonates within the sociopolitical milieu of the time. You've also got to wonder who the consumer for this drawing was. A patron who commissioned a study? Another artist seeking inspiration? Its existence as a tangible object within its historical context raises interesting questions about accessibility and artistic influence. Curator: We see similar floral arrangements pop up throughout decorative arts, which makes me think the artist or client had access to other visual motifs, influencing popular aesthetics. These images perpetuated an accepted status quo and visual taste. Editor: Which leads us to consider the power dynamics inherent in controlling representations of beauty and nature. These floral arrangements reflect back the culture that cultivated them—and, simultaneously, it sets trends for what beauty is, reinforcing established paradigms. The sketch could be seen as the quiet negotiation of power reflected in pencil strokes. Curator: That makes me re-think about its delicate simplicity and subtle power, framing it within a wider historical narrative about art production and dissemination. It becomes part of that early modern commerce of imagery. Editor: Agreed. It brings another layer of nuance and consideration to our appreciation of the drawing.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.