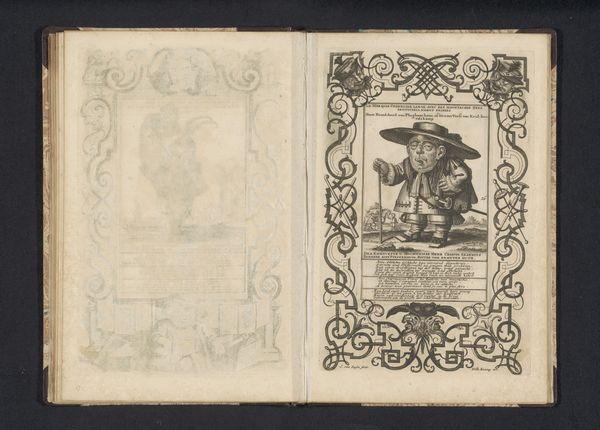

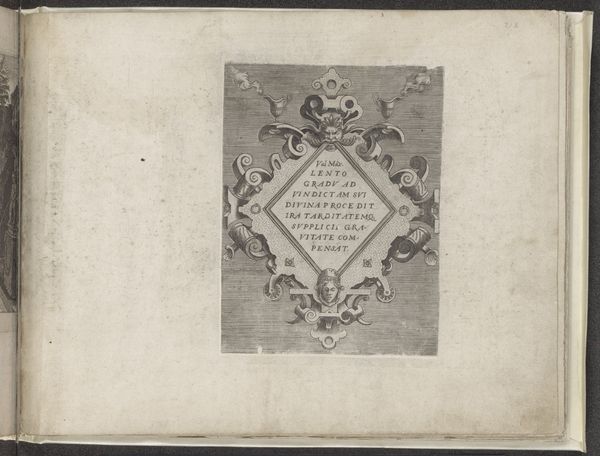

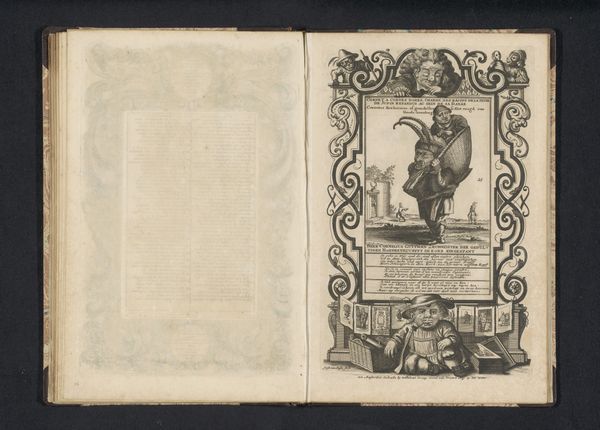

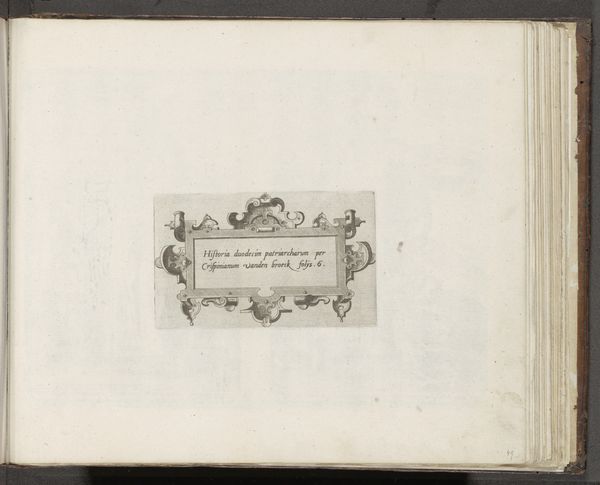

Titelprent met titel in lijst van penselen, oren, neuzen, monden en ogen c. 1663 - 1666

0:00

0:00

drawing, graphic-art, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

graphic-art

#

baroque

# print

#

line

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 143 mm, width 199 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What a curious little print! It's titled "Titelprent met titel in lijst van penselen, oren, neuzen, monden en ogen", which translates to "Title print with title in frame of brushes, ears, noses, mouths and eyes". The artist is Giuseppe Maria Mitelli, and it dates from about 1663 to 1666. Editor: My first impression is playful, even a bit bizarre. The border is unsettling yet kind of humorous. It seems to be inviting you in while simultaneously mocking you. Curator: It's fascinating how Mitelli uses these disparate elements—body parts and artists' tools—to create a cohesive frame. This print functions as the frontispiece, a kind of title page, to a series of engravings on the techniques of etching and engraving itself. These prints disseminated ideas and served as visual rhetoric. Editor: Right. And the choice of imagery speaks volumes about the artistic process as it was understood at the time. The brushes clearly represent artistic creation and production. But why the disembodied ears, noses, eyes, and mouths? What are those intended to suggest about art creation? Curator: I would argue it is because sensory experiences were central to early modern epistemologies and definitions of the "good artist". Remember, at the time, skill and talent were often framed as things learned by observation, study of the body, and apprenticeship. Editor: So, these fragmented body parts become symbols of perception, judgment, and skill. A painter isn’t just someone with a brush but someone who truly sees and understands. Even their capacity to hear well! It gives art-making a holistic, human dimension. The very letters in Mitelli Intaglio resemble small grotesque human forms themselves. Curator: Exactly! It points to a key tension in artistic production: skill vs. artistry, technical know-how, versus intellectual thought and sensibility. Moreover, by framing the intaglio as something inherently sensory and rooted in the body, he is further trying to suggest who could and should become an engraver. This print served not only to communicate knowledge but also to help define an artistic lineage. Editor: It's a small work, but it encapsulates a whole world of artistic understanding. I’ll never look at a title page the same way. Curator: It's a wonderful demonstration of how deeply entwined the practical and theoretical were in the 17th century art world. These seemingly random body parts tell a deeper cultural story.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.