daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

16_19th-century

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

united-states

#

genre-painting

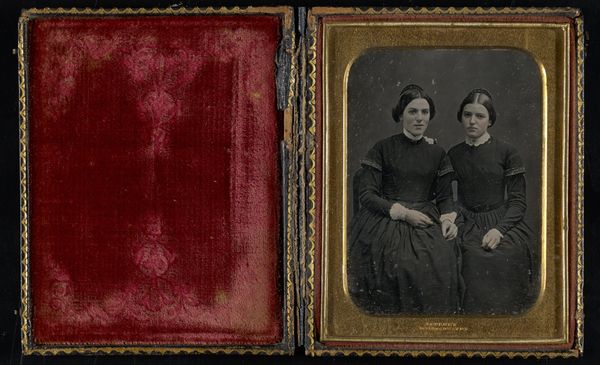

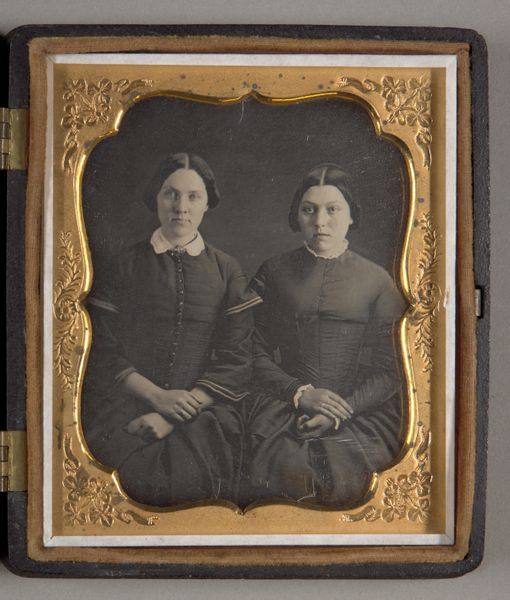

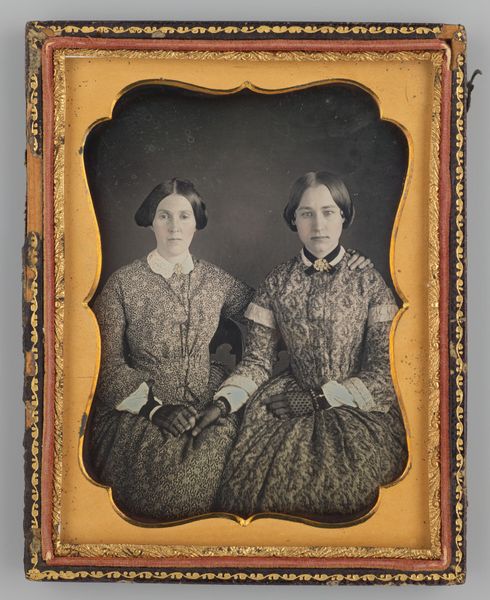

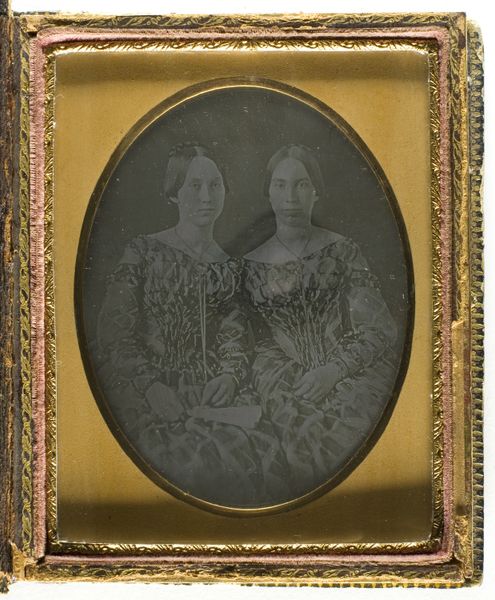

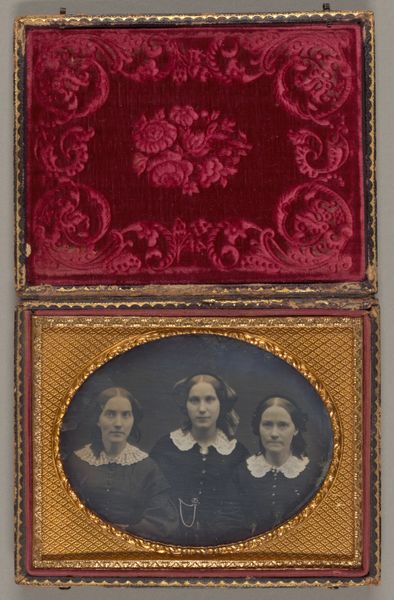

Dimensions: 10.7 × 8.2 cm (4 1/4 × 3 1/4 in., plate); 12 × 19 × 1 cm (open case); 12 × 9.5 × 1.9 cm (case)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This is an untitled daguerreotype by Albert George Park, created around 1855. It's a portrait featuring three women, now part of the collection at the Art Institute of Chicago. The details in the gilded frame alone indicate how highly valued photographs were becoming during the mid-19th century. Editor: The solemnity of it strikes me immediately. Their faces are quite serious, even stern. It feels very contained, composed… almost austere, yet, because it's a photograph rather than, say, an oil painting, there is still a documentary quality that suggests veracity, honesty. Curator: Daguerreotypes, unlike later photographic processes, created a single, unique image on a silvered copper plate. Photography, in the early Victorian era, played a democratizing role by putting images within reach of middle-class families, but it also served the aspirational goals of the rising bourgeoisie, and so this kind of portraiture allowed them to engage in displays of kinship and solidify social ties in ways previously reserved for the elite. Editor: I see how these photographic images helped families make these intimate displays to each other, a symbolic and actual connection, that endures to this day. Their dresses are nearly identical, dark fabric with those delicate white collars…the lace, the buttons, I find them really moving and yet uniform, which must mean something… perhaps these women are sisters? Curator: Yes, perhaps so, or cousins even, the clothing really offers a certain commonality. I think one of the intriguing things here is how these portrait studios, even those in small cities across the United States, fostered their local visual cultures. There’s so much implied, a lot we can intuit based on socio-cultural understanding, but also so much we’ll never truly know. Editor: True. The mirroring between them, and the physical linking by placing hands, feels very potent. It speaks to belonging and those hidden social bonds of affection that connect us all. Something this physical object made, captured, made forever. Curator: The portrait marks time and stops it, if only momentarily. An ephemeral form made timeless. I’m really drawn in by its visual evidence. Editor: Absolutely, it brings a different type of remembrance, in ways that reveal emotional truths with symbolic form and pose. The women's physical stillness adds depth and complexity in considering who they were to each other, what place did this portrait hold in their lives, and how memory lives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.