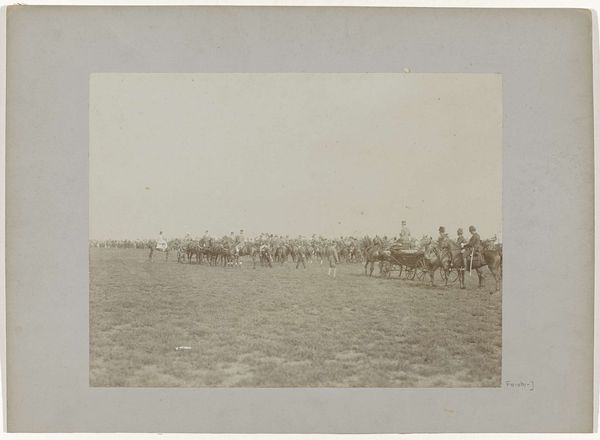

Dimensions: 13.3 × 17.9 cm (image/paper); 52.8 × 63.7 cm (album page)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This gelatin-silver print, currently housed at the Art Institute of Chicago, is attributed to Gustave Le Gray and dated to 1857. Although it’s untitled, it depicts a line of mounted soldiers in what appears to be a field or training ground. Editor: The overwhelming feeling is one of rigid discipline, yet there’s something… almost ethereal about it. It's as if the individual soldiers are fading into a uniform whole. The composition itself is interesting, that receding line diminishing to nearly nothing against the huge, empty sky. Curator: Precisely. What fascinates me is Le Gray’s technical process here. Working with collodion required meticulous preparation and immediate execution. The albumen print would then need sunlight to properly expose the print. To consider the sheer labor behind capturing such a large formation in such a nascent stage of photography is astounding. And also considering all that’s needed when on the field. Editor: It brings to mind classical depictions of the Roman legions—a display of ordered might. The horses, largely white, act as almost spiritual steeds carrying them to either greatness or some terrible conflict. What is the significance of the light sky in your understanding? Curator: As well as a product of Romanticism and the need to illustrate, there is also the more industrial context; consider how the advances in glass plate technology and portable darkrooms facilitated capturing these large-scale scenes on location and increased the accessibility and mass reproduction of artworks during that period. What it brings about, also, is questioning of whether or not photographic advances democratize art itself. Editor: Indeed. Perhaps Le Gray intentionally left so much blank sky to mirror the limitless aspirations or potential of these young men going off to war. There’s that powerful juxtaposition: men bound by military structure against a boundless sky filled with dreams of something bigger than themselves. There may be many symbolic intentions in capturing such raw feelings of duty versus one's soul. Curator: So both process and image become inherently intertwined with the artwork, which both dictates our perception of the time period, of conflict, as well as its relationship to fine art in this era. Thank you for such an intriguing discussion. Editor: A pleasure. This artwork really offers up different pathways for reflection.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.