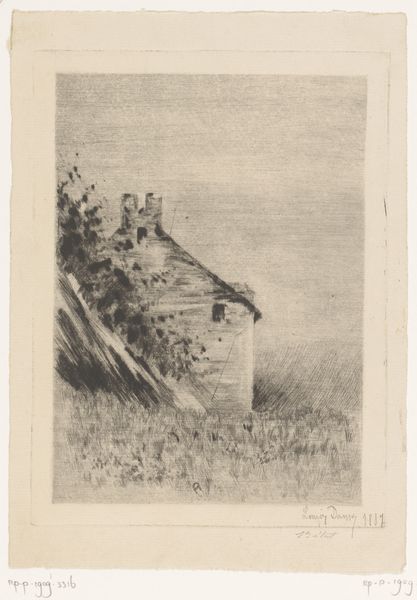

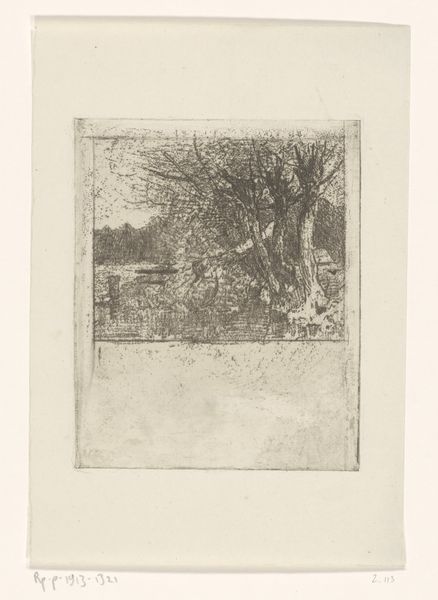

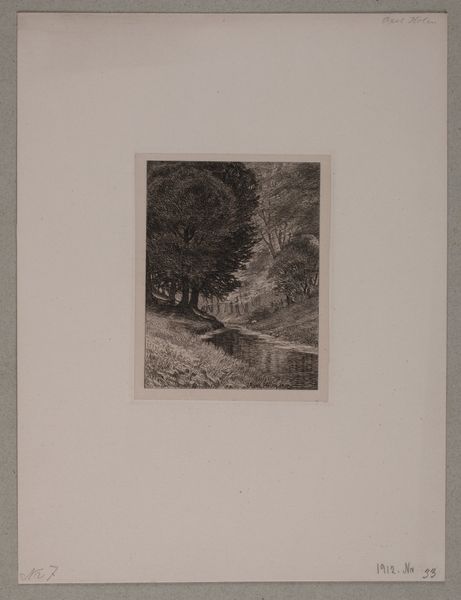

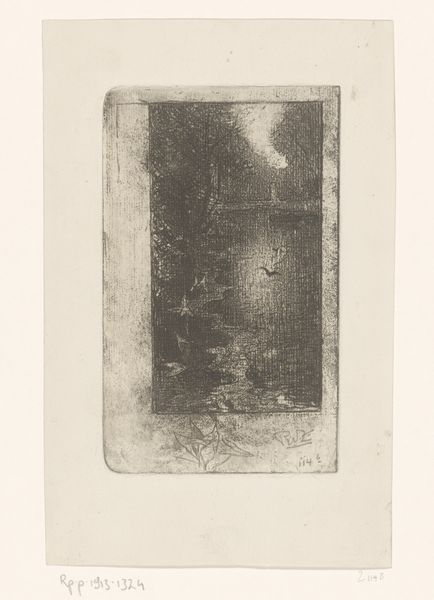

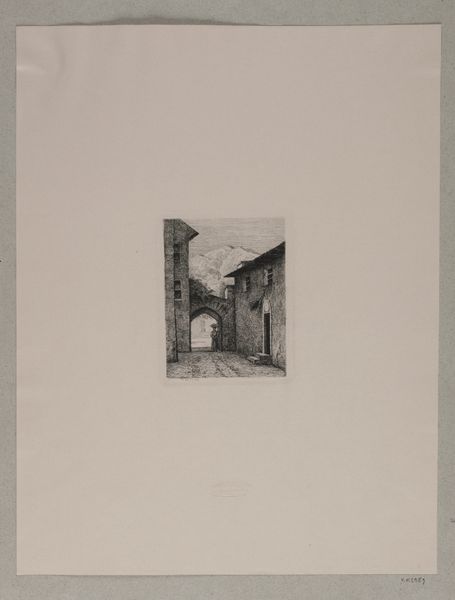

print, etching

# print

#

etching

#

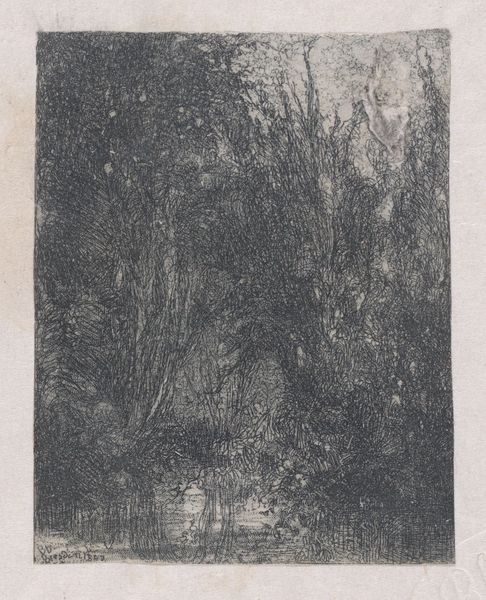

landscape

#

realism

Dimensions: 216 mm (height) x 140 mm (width) (plademaal)

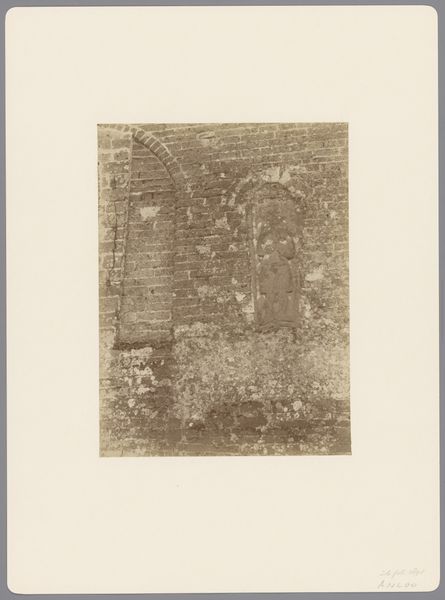

Editor: We’re looking at Emil Petersen’s “Husmur med blomster,” an etching from the late 1890s or early 1900s. It feels… intensely private. The shadowed doorway and brick wall, almost engulfed by blooming vines… what do you make of it? Curator: This print speaks to the rising middle class and the art market's interest in scenes of domesticity and the picturesque in that era. The garden setting and implied seclusion catered to a desire for quietude. Do you think Petersen is merely representing a pleasant scene? Editor: I hadn’t considered that it could be intended for a specific buyer. It feels…accessible but maybe also just a scene anyone could admire, so who would be more likely to purchase such work? Curator: Well, printmaking at the time became increasingly affordable and available. Think about how this imagery circulates: what does it say about whose vision of beauty was privileged and sold? This isn't simply a landscape; it's a manufactured idea of one. Editor: Ah, it’s the *idea* of that cultivated, comforting garden scene being bought and sold, not just the actual landscape! So even the desire for "quietude" becomes commodified. Curator: Exactly. Now look at the quality of the line, the attention to the textures of brick and blossom, do you feel the printmaker approves, challenges, or does something different entirely in representing the rise of the domestic in the public view? Editor: I see how it captures a certain social yearning, framing domesticity itself as a desirable—and marketable—commodity, and it challenges me to look more carefully at our assumptions about idealized settings and who they include and exclude. Thank you. Curator: It highlights how much the personal is often inherently political, or at least connected to prevailing socio-economic trends. A single print becomes a window into cultural values.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.