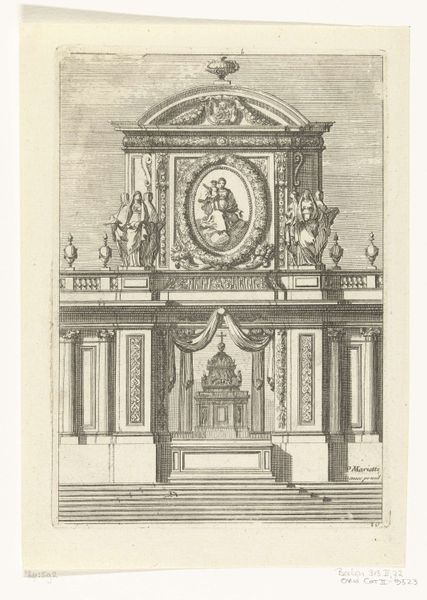

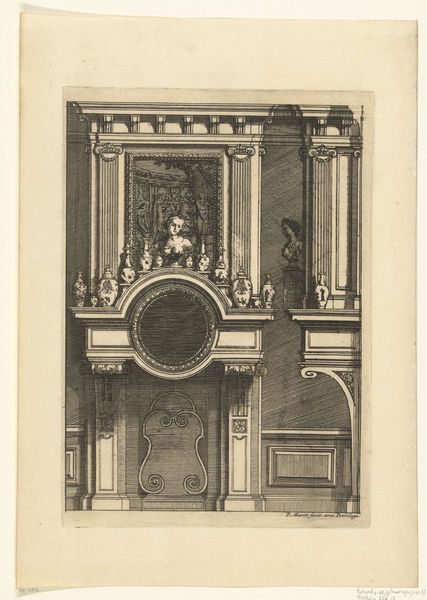

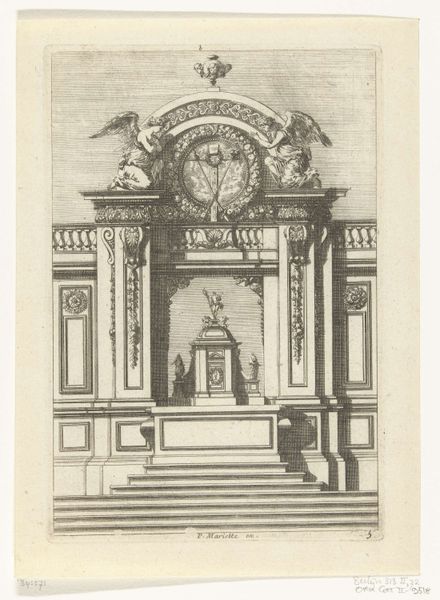

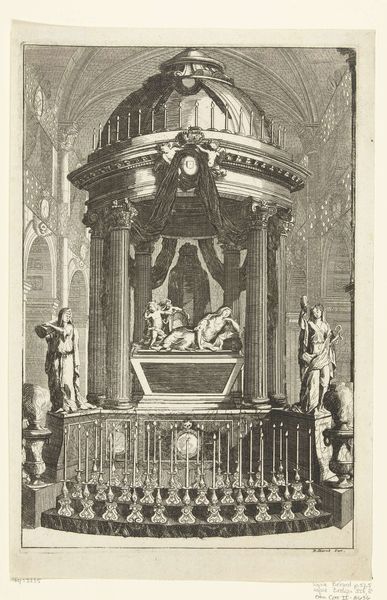

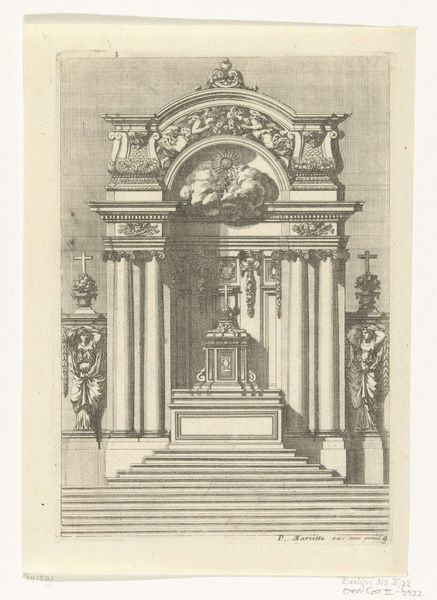

print, engraving, architecture

#

baroque

# print

#

pen sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

old engraving style

#

form

#

pen-ink sketch

#

line

#

pen work

#

engraving

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 196 mm, width 134 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is Jean Lepautre’s "Tabernakel op altaar," dating from about 1666 to 1693, a print in the Rijksmuseum’s collection. The level of detail in the engraving is amazing! It makes me think about the sheer craftsmanship that went into creating these images, and the scenes that they're portraying. How do we read a piece like this through a broader historical context? Curator: That’s a key question. Consider this image's function: engravings like these, particularly of altars and tabernacles, circulated widely. They were not simply aesthetic objects, but tools for disseminating architectural styles and religious ideologies. In the Baroque era, the Church heavily relied on visual rhetoric. How does the architectural design reinforce specific doctrines? Editor: I see the very ornate decorations, the grand columns, the theatrical drapery – it's designed to overwhelm and inspire awe. Is it trying to communicate something about power, both divine and earthly? Curator: Precisely! The imposing scale, even in print, reflects the Church's desire to project power and authority. These altars became stages for performing the sacred drama of the Mass, and the visual spectacle served as a powerful means of engaging the faithful. What effect might repeated imagery, as shown here, have on shaping viewers’ perceptions, or on commissioning clients? Editor: It’s almost like architectural propaganda! I never thought about engravings having so much influence on design. Curator: Exactly. These prints codified visual expectations for sacred spaces. Reflect on the interplay of art, religion, and politics; it reveals how deeply embedded these structures are. What’s your take away from this? Editor: That the engraving isn't just a pretty picture but a vehicle for power! Curator: It really illuminates the potent social force of religious art and its dissemination, doesn’t it?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.