photography

#

portrait

#

photography

#

historical fashion

#

19th century

Dimensions: height 104 mm, width 63 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

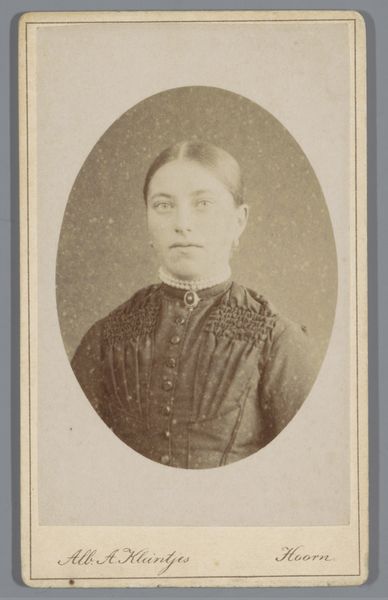

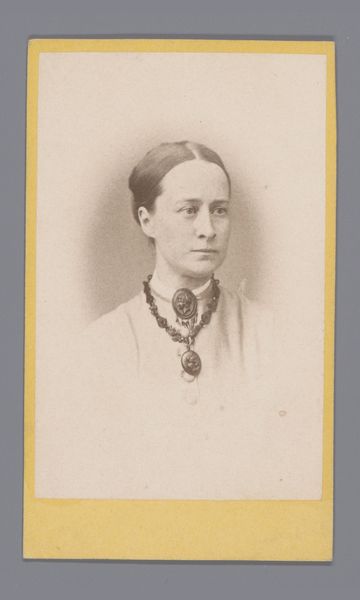

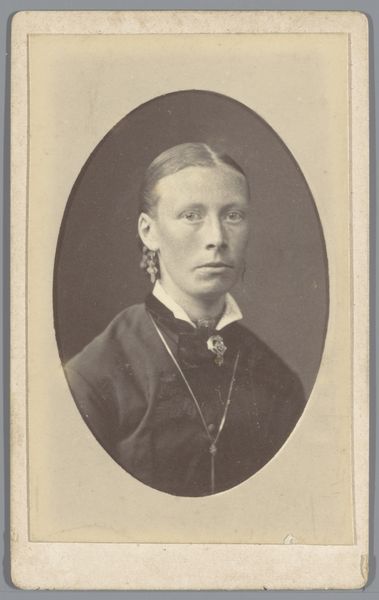

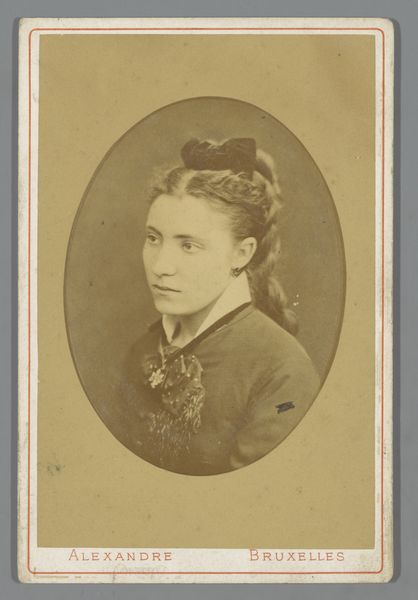

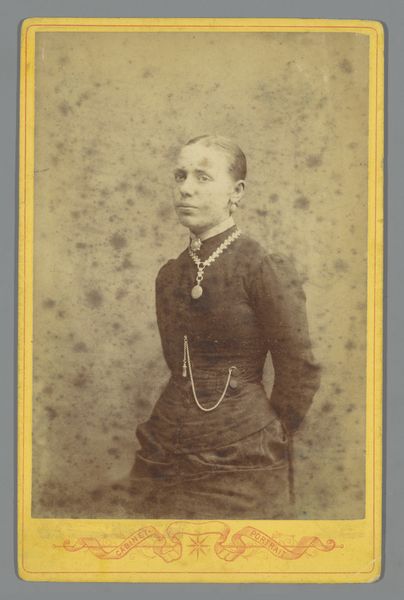

Curator: Looking at this piece, I'm struck by the intensity in her gaze. It's quite arresting, really. Editor: You're responding to "Portret van een onbekende vrouw" which, according to records, was captured sometime between 1879 and 1885 by Johann Georg Hameter. It's a photograph, an example of portraiture from that period. The title translates simply to "Portrait of an Unknown Woman." Curator: "Unknown" always adds a layer of mystery, doesn't it? The lack of knowing her name or story only deepens the impression she makes. I keep wanting to give her one, a life. Does that happen to you? Editor: Constantly. As someone from the twenty-first century engaging with art of the nineteenth, my response is mediated through everything that has transpired historically and artistically since then. I think, considering the time this photograph was taken, that it’s interesting to consider the rise of photography’s place in social documentation, like an early version of our ubiquitous “selfie” culture today. Curator: Interesting. So different from painting at the time, where portraits were mainly for the wealthy. Now, with photography, more people could have their images recorded. I wonder what it was like for this particular woman? Was this an exciting, daring new venture, or just part of daily life in 19th-century Netherlands? And, look how rigid she stands: almost severe. She's in a world of change, perhaps afraid of it, but definitely ready for anything. I notice that, as she appears very somber, even tough, she wears jewelry—very discrete. The severe bow at her chest as well. What do you make of it? Editor: Well, what jumps out for me is how photography democratized portraiture. For the growing middle classes of Europe, this afforded a sort of accessibility previously unheard of; the act of portraying oneself or one’s family for posterity and future generations—previously exclusive to aristocracy or gentry—becomes socially ubiquitous in ways previously unseen. She could simply be someone exercising her access to this medium as it gained more mainstream use in the mid to late 19th century. Curator: Maybe it’s a bit of both—exercising freedom in a still quite unfree world, where photography, along with increasing freedoms in industry, in lifestyle, offered an image of emancipation—of being… who? Editor: And these photographic portraits – often presented in cartes de visite – would, as with similar analog versions later in the twentieth century and social media now, travel vast networks of social connectivity: from immediate and extended family relations to commercial associations to, even, romantic attachments! Curator: Very fascinating! Seeing this makes me want to step back into my own portrait, so to speak. A fresh way of perceiving old memories. Thank you! Editor: Always glad to offer historical insights. I do encourage everyone to find themselves within each historical artefact they meet: the beauty and power of images as communicative as this rests entirely in their lasting effects, throughout our modern society.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.