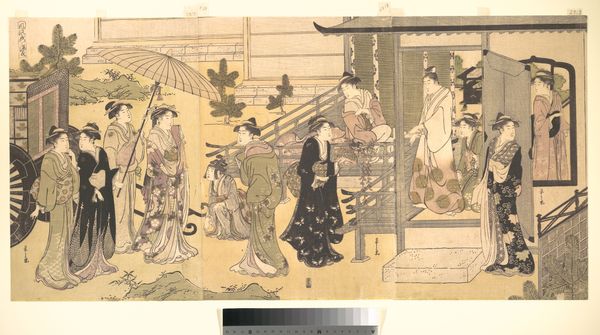

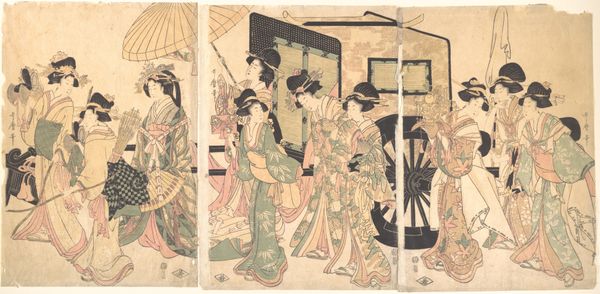

Parody of the Episode of the Third Princess (Modoki Onna San no Miya) 1780 - 1795

0:00

0:00

print, woodblock-print

# print

#

asian-art

#

ukiyo-e

#

figuration

#

woodblock-print

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: Image (each): 15 3/8 × 10 3/8 in. (39.1 × 26.4 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

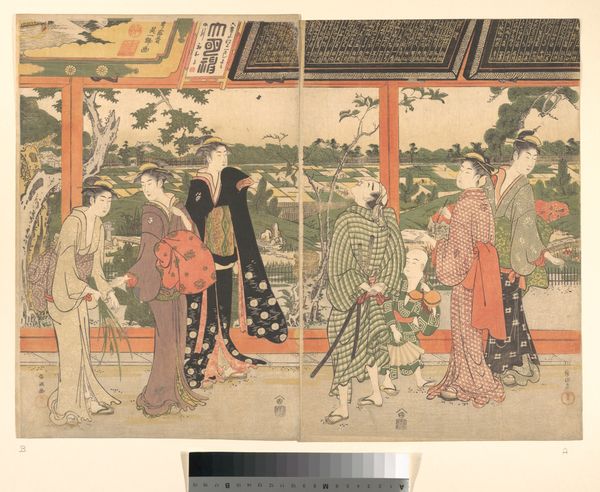

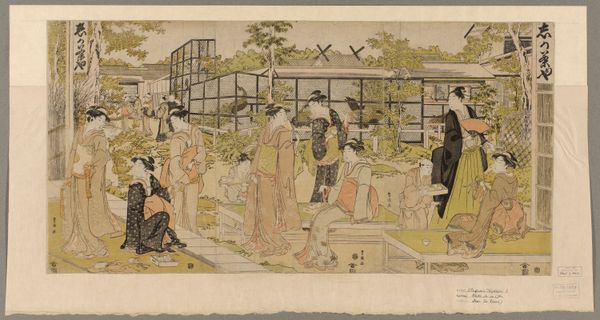

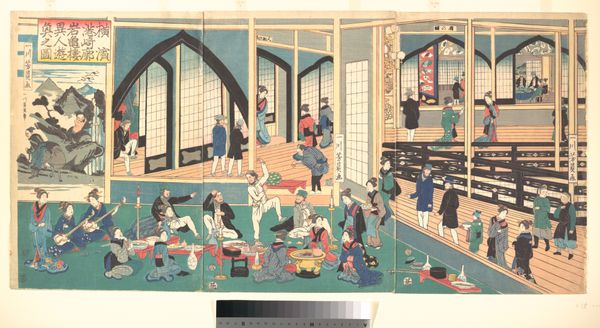

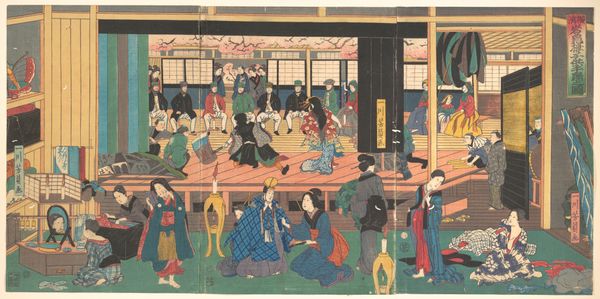

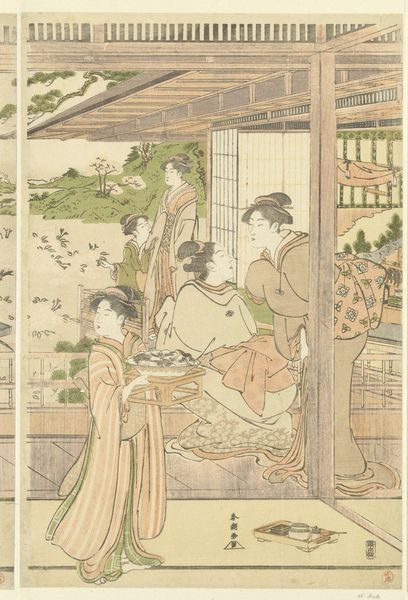

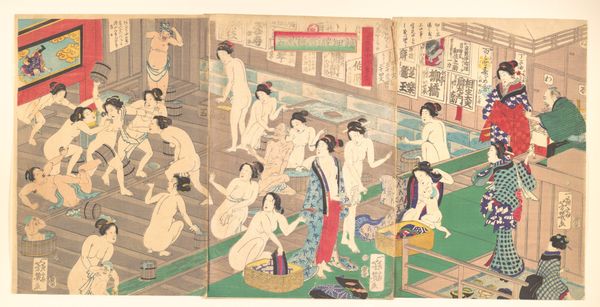

Curator: What a vibrant snapshot of late 18th-century life! This woodblock print, created by Katsukawa Shunchō between 1780 and 1795, is titled "Parody of the Episode of the Third Princess (Modoki Onna San no Miya)." Editor: My initial impression? It’s bustling! The composition, split almost in two halves, really pulls you into the intricate details of everyday life for these women. What struck you first? Curator: It's definitely the interplay of leisure and labor. We see this large group of figures, seemingly women, positioned inside what looks like a wealthy residence. This print reflects ukiyo-e traditions but with a slightly critical lens. The choice of woodblock as a medium is crucial, isn't it? Ukiyo-e prints democratized art. They made scenes of pleasure and fashion accessible to a broader public than, say, a unique painting. Editor: Precisely. Woodblock printing allowed for mass production, facilitating the dissemination of these images, and informing, if not driving, social trends. But I wonder about the institutional framework that would dictate consumption and appreciation. What's the significance of "parody" in the title? It points to a specific literary context, which could determine its audience and impact. Curator: Ah, that’s key! The "parody" likely points to a knowing audience aware of classical literature, able to appreciate the subtle commentary on social mores. The skilled labor involved in creating such prints, from the artists to the block cutters, contributed significantly to shaping visual culture, which would also shift these power dynamics of gender in public imagination. Editor: And let's consider how the spatial arrangements within the print contribute to our understanding. We see clear markers of class and social hierarchy at play here. Also, the presence of latticework creates separation. What does this division do to our understanding of female roles within the broader society? Curator: The latticework serves both as a physical and metaphorical barrier, emphasizing the restricted mobility and social visibility of these women, even within a space presumably designed for entertainment. The layered colors speak to me about the rich tradition behind such pieces, a complicated mix of mineral and plant-based pigments painstakingly applied to capture specific impressions. Editor: Thinking about its historical place, I wonder how the museum setting alters our relationship to it? As opposed to its original consumption within contemporary Japanese society. Does framing it as "art" inherently shift its function from everyday commodity to high cultural artifact? Curator: Absolutely, by being placed in an institution like the Metropolitan Museum, the print’s status is elevated. That shift highlights a key tension between its origins as a commercial product, but, more importantly, showcases cultural touchstones through visual language, inviting reflection. Editor: So it goes from a piece reflective of the time to a piece documenting the time, a historical snapshot as we view it now. Curator: Exactly. Examining both the object and the hands that created it provides insight into our complex cultural landscape. Editor: And from that view of culture, to a lens that scrutinizes its narrative, the artwork definitely holds our attention as a commentary of women's culture and class divides of Japan's Edo period.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.