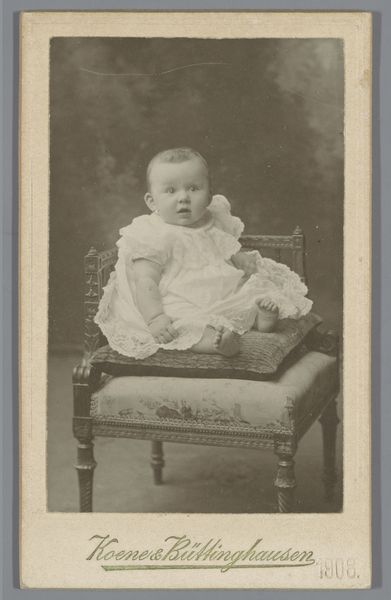

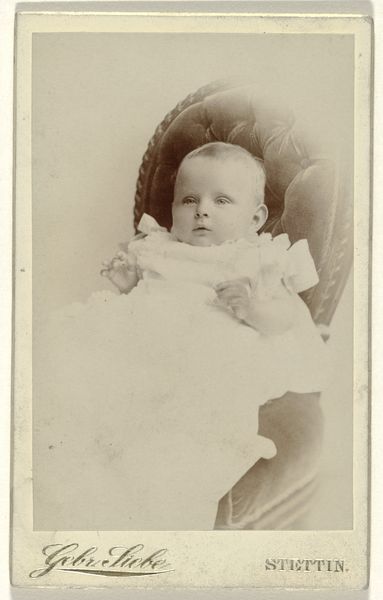

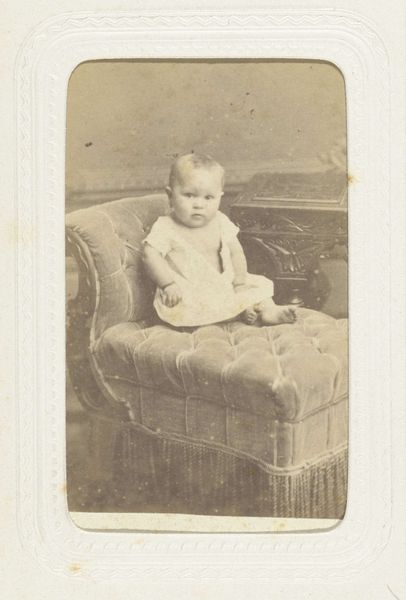

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

archive photography

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 82 mm, width 54 mm, height 105 mm, width 64 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: It’s striking, isn't it? The stillness in the baby's eyes amidst such an ornate setting. Editor: It really is! The texture feels so soft, despite being a gelatin silver print. I am immediately struck by the inherent tenderness in such antiquated archival images. The image dates from about 1864 to 1887 and it's listed in the Rijksmuseum's collection as "Portret van een baby op een stoel" – "Portrait of a baby on a chair" in English. The studio is attributed to Wegner & Mottu, whoever that may be... Curator: Wegner & Mottu, while relatively obscure now, represent a fascinating facet of the emergent photography market in the mid-19th century. They likely catered to the burgeoning middle class seeking ways to commemorate life events. Baby portraits, like this one, served not just as keepsakes but also as social signifiers, cementing the family’s position. Editor: Yes, precisely, it represents such careful staging for symbolic resonance. Note the chair; almost a throne. The child becomes a tiny potentate, hinting at future prosperity. Baby portraiture had all the trappings of the aristocratic portraits of bygone eras. Curator: Certainly, though it is worth considering whether those symbols carry genuine weight, or whether this portrait is not more a reflection of parental hope rather than an assured path. The trappings of power – here the chair and the carefully composed setting – were meant to project aspirations onto the blank slate of childhood. It becomes about crafting a narrative for the future through a controlled present. Editor: Still, there's the unavoidable visual cue. In those days, this must have read as "importance." The parents understood and exploited the visual semiotics, consciously or not. But, tell me, does this reading into such symbols always need to take place, to gain satisfaction or cultural and political readings from it? Is a sweet photograph enough in itself? Curator: Context informs how we see; it provides us with greater nuances. An adorable photograph can be also read as a carefully constructed symbol that speaks volumes about its time, power, and ambition. It’s a small photograph holding significant societal data, not always obviously there on the surface. Editor: Yes, it provides more in-depth insights. In truth, my first naive response misses such depths entirely! Curator: Indeed! But even the naivete is part of the experience, don't you think?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.