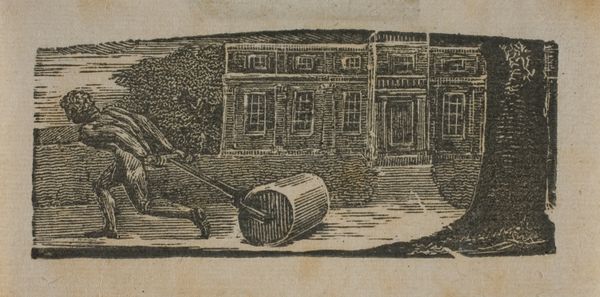

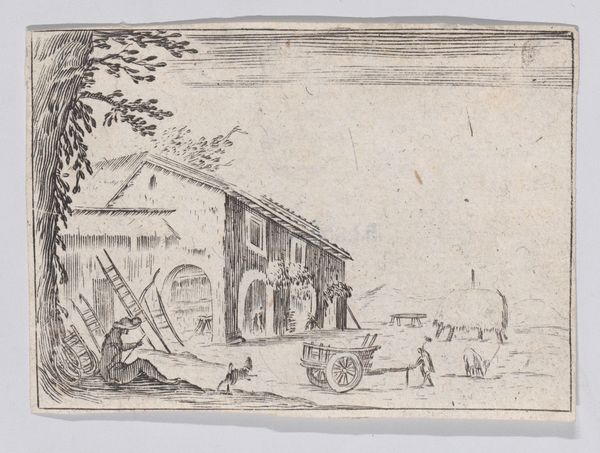

A Rolling Stone Is Ever Bare of Moss, from Thornton's "Pastorals of Virgil" 1821

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, woodcut

#

drawing

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

romanticism

#

woodcut

Dimensions: block: 1 1/2 x 3 1/16 in. (3.8 x 7.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: It's hard to look away from this little print. "A Rolling Stone Is Ever Bare of Moss," created around 1821 by William Blake. The title itself is enough to spin you into endless thought, isn’t it? Editor: It’s… intense. The stark contrast, that dark figure straining to move what looks like a giant drum. It’s unsettling, actually, a vision of labor bordering on the Sisyphean. Curator: Blake originally created it to accompany Thornton’s "Pastorals of Virgil," but something tells me this engraving transcends any mere illustration. It’s more than just a pastoral scene gone askew; I see reflections of industrialization and the individual’s struggle against relentless forces. That stone... what do you make of that weight the man pulls? Editor: In many ways, the stone becomes a metaphor for unfulfilled potential. The labor is clearly demanding and oppressive, it speaks to social and economic exploitation. Blake seems to be asking: At what cost does progress come? The cost for the body and perhaps the soul. Curator: Exactly! The composition itself adds to that tension. The figure almost blends with the darkness and then leads you up to this dark looming building; even though it is simple, one feels how the shadow is trying to overwhelm this person. Editor: I find it poignant how the woodcut’s lines give a real sense of rough texture. There's little respite, is there? And that looming structure in the background, like a promise or a prison, depending on your view. Curator: Prisons and promises! What you just said just gave me a chill. It encapsulates how Blake managed to convey such complex emotional and political ideas through the humblest means, even in these modest illustrations. Each one feels like a world unto itself. Editor: Precisely, this artwork, at its core, feels deeply connected to questions around societal progress and who exactly profits. There is also a discussion of agency and physical constraints related to larger social issues of Blake's time. It reminds us of how much those discussions echo still. Curator: To think of Blake painstakingly carving that scene... a single gesture, repeated endlessly, to show one single scene. There's an existential wink here, maybe he is sharing more about himself that one thinks? Editor: Yes, Blake created a tiny, yet potent mirror reflecting larger systems. Its ability to provoke discussion after all these years is a testament to its relevance.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.