drawing, pencil, chalk

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

landscape

#

pencil

#

chalk

#

15_18th-century

#

realism

Copyright: Public Domain

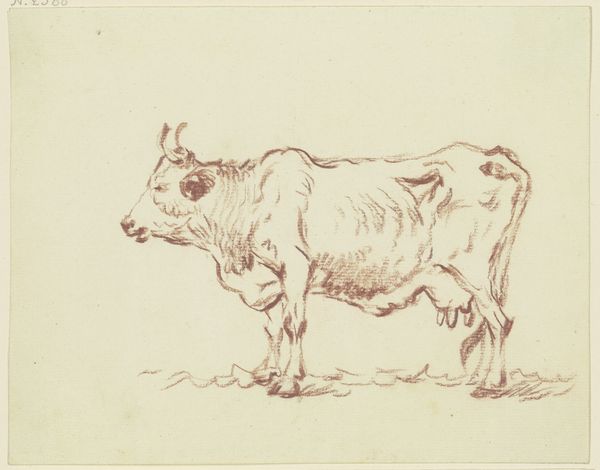

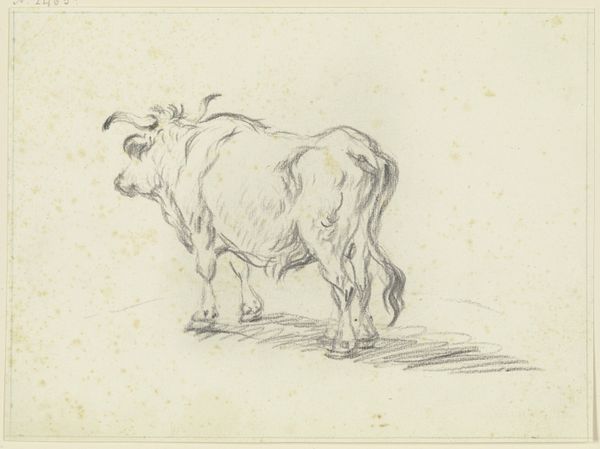

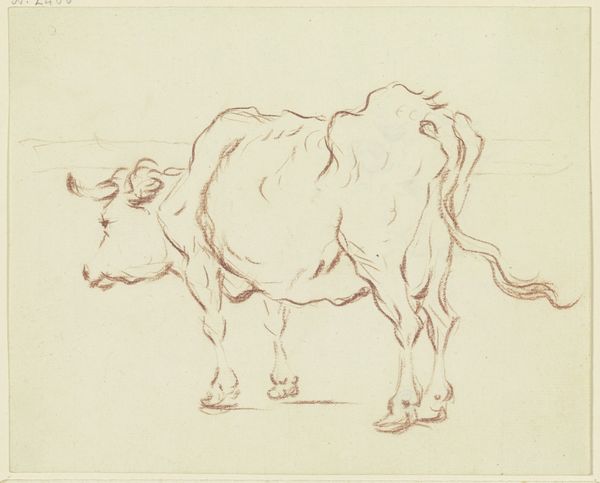

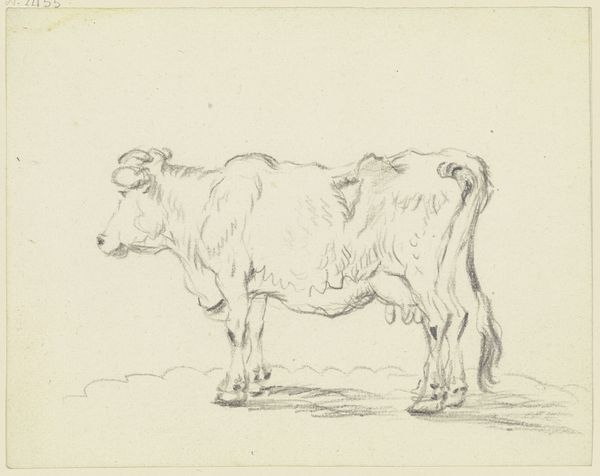

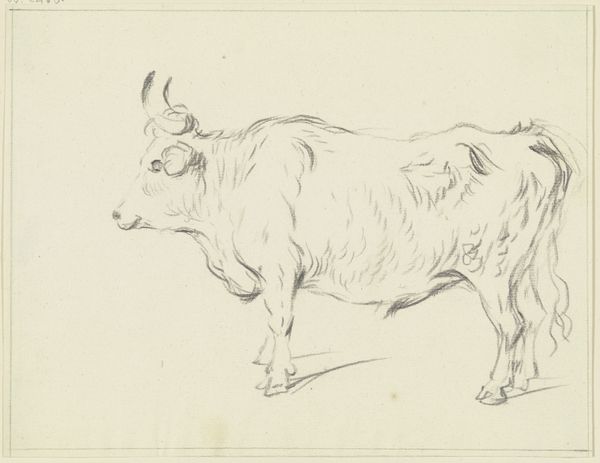

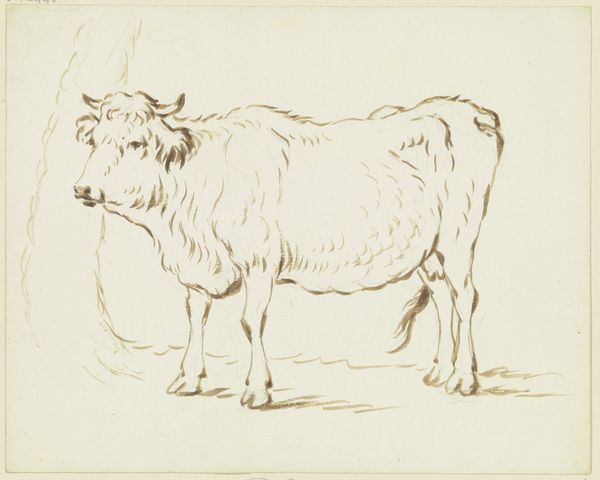

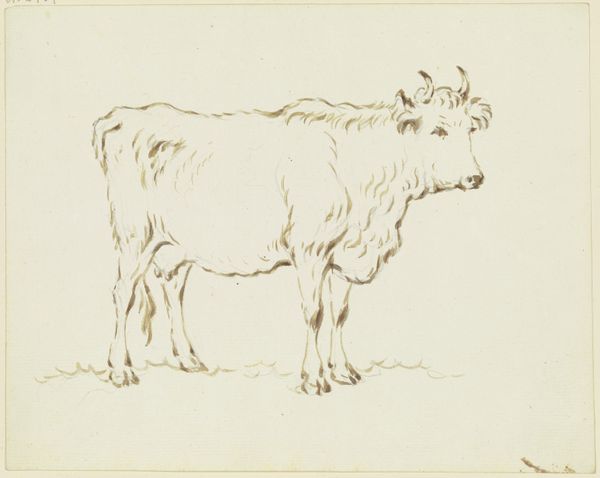

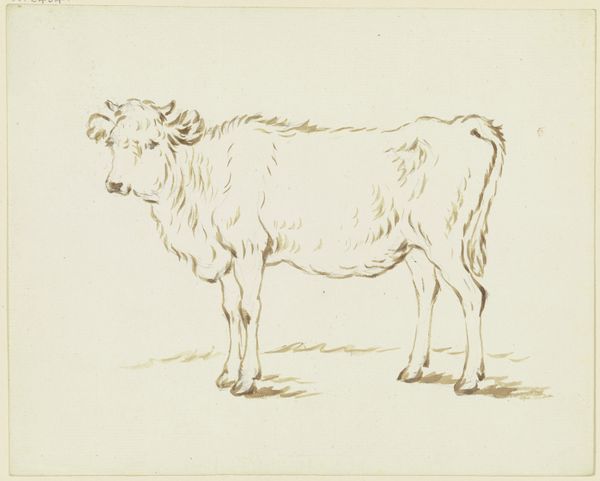

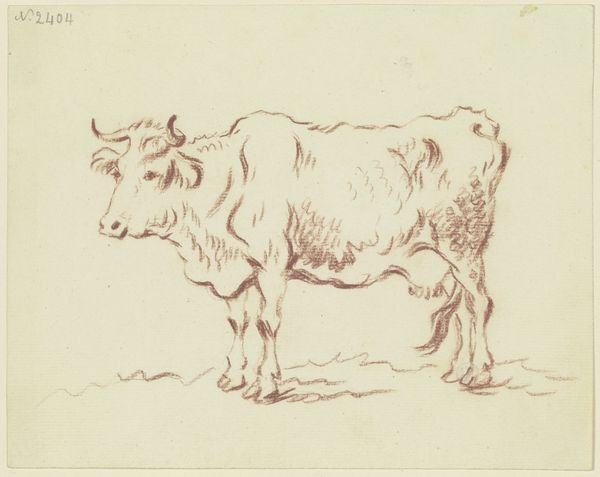

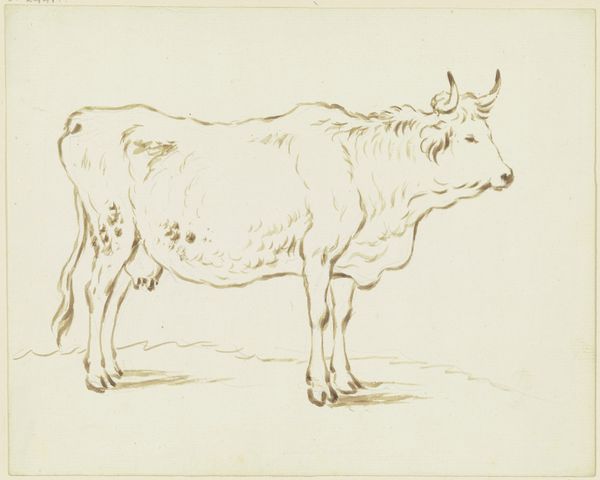

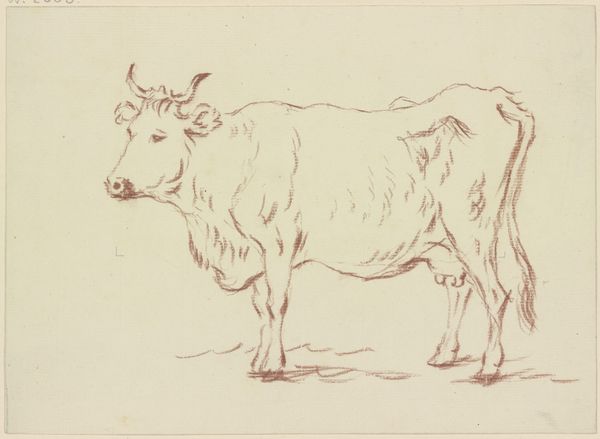

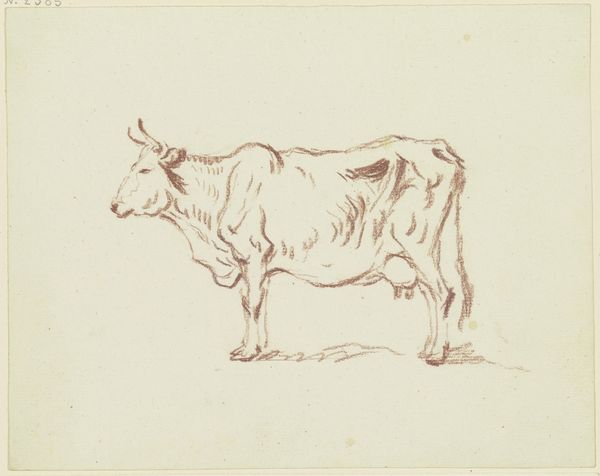

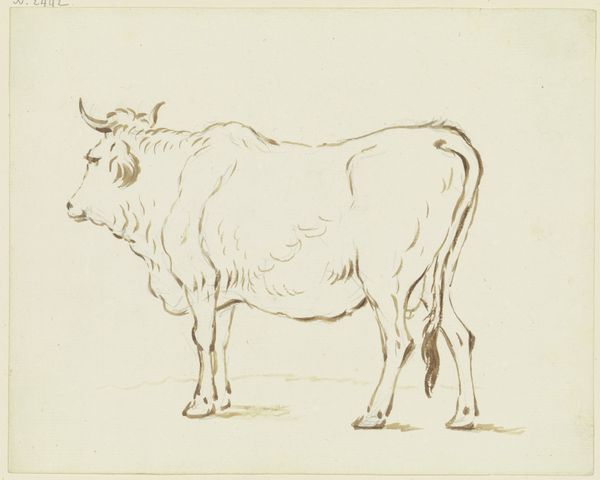

Curator: Standing before us is "Stehender Ochse in leichter Verkürzung nach rechts," which translates to "Standing Ox, Slightly Foreshortened to the Right," a pencil and chalk drawing now residing here at the Städel Museum. Editor: My initial impression is one of quiet observation. There's a sense of calm and the piece feels unpretentious. The use of light and shadow gives the ox a gentle solidity. Curator: Precisely. It is quite a study. Consider how the image of the ox functions throughout centuries of artistic creation, and the connotations attached to the animal as a symbol: virility, strength, patient labor, but also docile submission and even sacrificial victimhood. What do you think of when you look at it? Editor: It's interesting you say "sacrifice", because its sturdy, almost stoic, pose, along with that slight turn of the head, hints at a potential awareness, perhaps even a kind of burdened consciousness. The animal stands firmly planted, yet appears somehow caught in an oppressive environment. It also occurs to me that these rural animals carry certain gender implications even today. What was the artist conveying in this work? Curator: Ah, an interesting question. Though unsigned, this naturalistic depiction embodies Enlightenment-era artistic principles with its commitment to depicting nature as objectively as possible. The ox is shorn of elaborate decoration, or narrative context—and presented as an exercise in rendering its essential forms through light and shadow. Its strength is revealed through its form. It feels symbolic of the very natural order these artists strived to capture. Editor: Still, within its formal clarity, there is something powerful about the choice of subject. By giving the ox its own portrait, doesn't this give the animal a sense of self and identity that had been previously denied? This bestial representation hints to broader intersectional themes related to how society views power and value. Curator: Well, in that sense, this ox could function as a symbol for humanity’s complicated relationship with nature—at once venerating and subjugating its power for its own means. Thank you for drawing out those contemporary connotations; it's a good way of appreciating its enduring impact. Editor: Agreed! Thank you. Now it gives us something more to think about than just its likeness, but what this image meant then and means now, so long as our own biases persist.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.