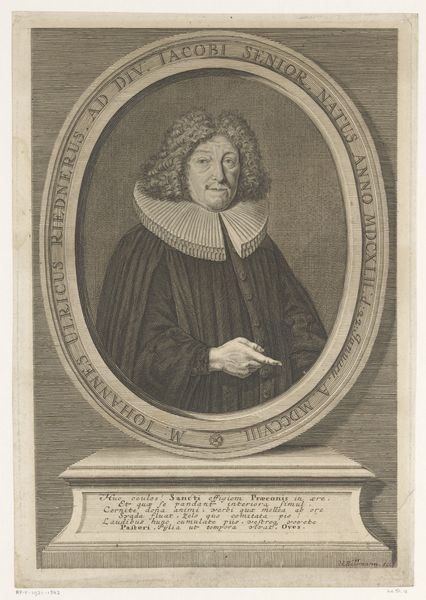

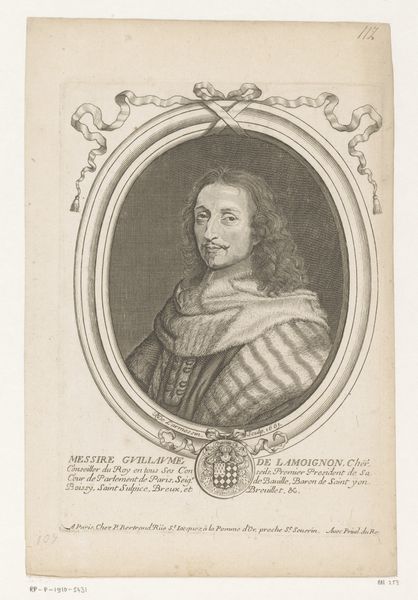

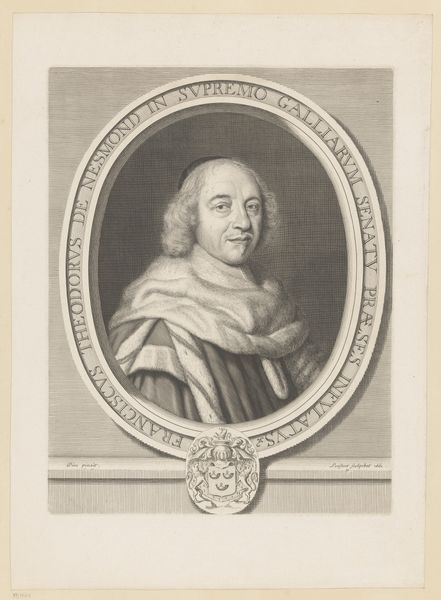

print, intaglio, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

intaglio

#

old engraving style

#

pencil drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 298 mm, width 192 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Good morning, everyone. Today, we’re looking at Johann Philipp Thelott's portrait of Guidobald von Thun und Hohenstein, an intaglio print dating from 1667 to 1671. Editor: My first impression is this has a really self-serious air, hasn’t it? Very stately and... almost severe? Even with the laurel wreath framing the portrait, there is something solemn and unflinching. Curator: Absolutely. The baroque period often utilized such ornamentation to ennoble and aggrandize the subject. Here, it serves to frame Guidobald von Thun, a prominent religious figure of his time. It is a historical painting made using engraving and other related techniques. Editor: Precisely. His vestments indicate a man of the church and high status—the artist really captured a sense of powerful, established authority. Note, also, how his gaze seems designed to meet the viewer's eye, projecting both command and...perhaps a hint of calculation? It speaks to how images can construct and disseminate power dynamics. The composition also shows Baroque characteristics. Curator: The choice to use print as a medium here is fascinating. By creating an easily reproducible image, it extends von Thun’s influence and image beyond the constraints of a single painted portrait. This work reflects a period when the church used art as a political instrument. I find it funny how relevant its history is in our modern age. Editor: And considering how controlled access to visual media was at this time, such portraits become key tools for constructing identities. How did they use portraits as tools of legitimation, and control public memory in the 17th Century? It's interesting to look at the role portraits such as these served within broader systems of power. And consider how engravings themselves become objects with their own biographies… Curator: I keep finding myself wondering, What was he really like? I like that the engraving lets us into the spirit of the age in some mysterious way. Perhaps he even has some juicy secrets of his own that he has failed to protect. Who knows? That sort of playful thinking is what truly makes it great. Editor: I completely agree; engaging with these works requires us to remember that they aren't objective depictions of reality but instead are imbued with societal power, ideology, and perhaps, something else to be remembered later. Curator: I am thankful for how revealing revisiting the past can be, what an enduring symbol! Editor: A good moment for thinking, for sure. Thanks.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.