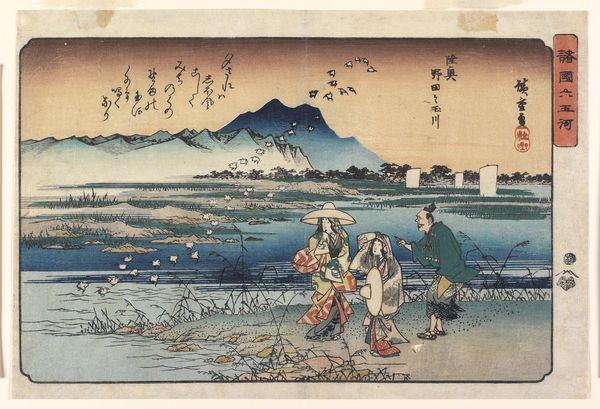

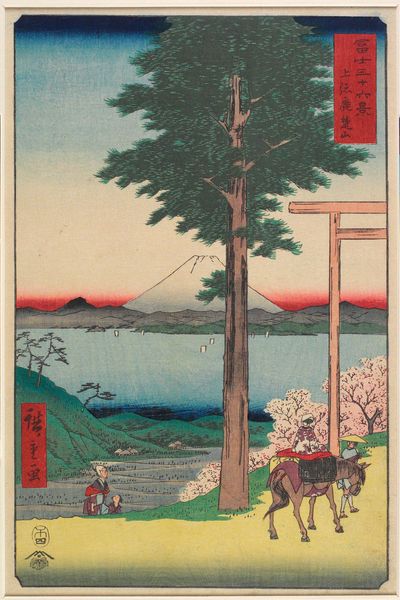

print, paper, ink, color-on-paper, woodblock-print

# print

#

landscape

#

ukiyo-e

#

japan

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

color-on-paper

#

woodblock-print

Dimensions: 6 × 8 3/4 in. (15.3 × 22.2 cm) (image, horizontal chūban)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This vibrant print, “Act VIII” by Utagawa Hiroshige, dates from around 1843 to 1846. It's a woodblock print, ink and color on paper, currently held at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. What’s your first impression? Editor: It feels simultaneously tranquil and theatrical. The composition, with Mount Fuji in the distance and those elaborately dressed figures in the foreground, seems carefully staged, almost like a tableau. Curator: Absolutely. Hiroshige masterfully combined landscape and figuration. This is ukiyo-e, remember – pictures of the floating world. Note the way the printmaking process allows for these clear lines, distinct blocks of color. Consider the labor involved, not just by Hiroshige but the team of block cutters and printers required to create this. Editor: Yes, the collaboration is key. And Ukiyo-e prints became very popular and circulated widely as commodities. Look at the two women – what social commentary is Hiroshige offering, if any? Are they actresses, or are they meant to represent members of the leisure class who were both consumers and subjects of these mass produced images? Curator: It's intriguing to consider the distribution networks that sustained this kind of art. Woodblock prints democratized art, moving it away from solely aristocratic or religious consumption to a wider urban audience. These images were circulated widely, both shaping and reflecting popular taste. The materiality itself, paper, ink, wood, facilitated this shift. Editor: And those popular tastes included historical dramas – hence the "Act VIII" title. The story connects this serene landscape to tales of loyalty, revenge and samurai. So it’s a complex layering – beauty, craft, history, and theatre, all filtered through the lens of 19th-century Japanese society. The social function is both decorative and narrative. Curator: Precisely. And Hiroshige managed to elevate an artisanal practice, ukiyo-e, to the level of high art through his unique skill. He harnessed the techniques to create enduring images, transforming the means of production into something quite extraordinary. Editor: It's a reminder that art is rarely born in a vacuum. Hiroshige’s art depended on social structures, material means, and a hungry public eager to engage with images of their world, both real and imagined. The story and process combine for lasting meaning.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.