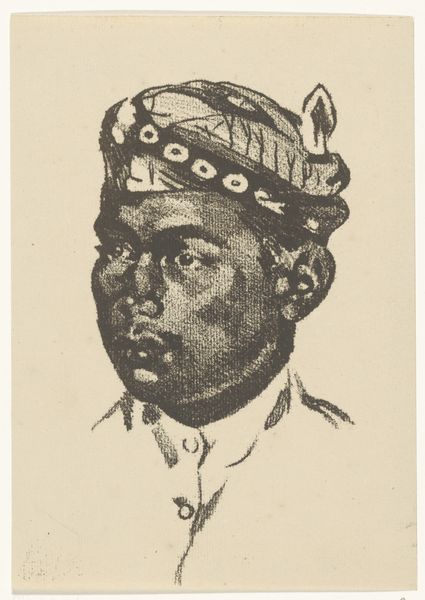

drawing, charcoal

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

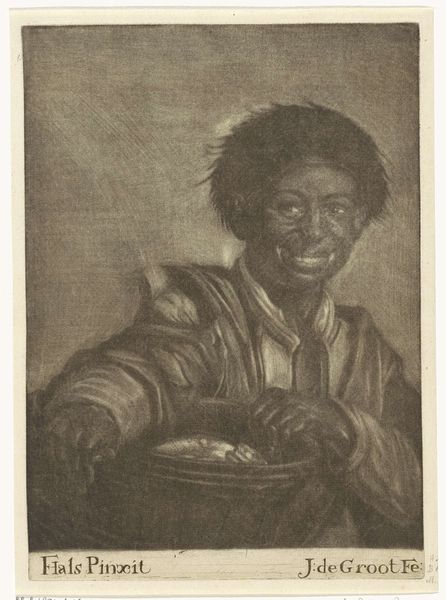

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

charcoal

#

realism

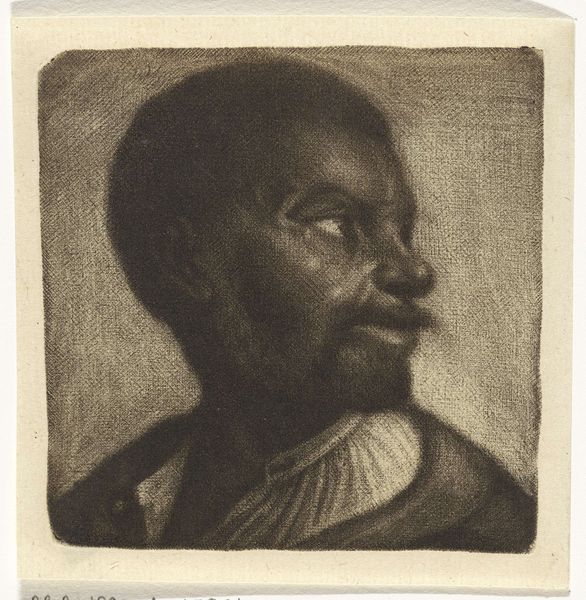

Dimensions: height 144 mm, width 140 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

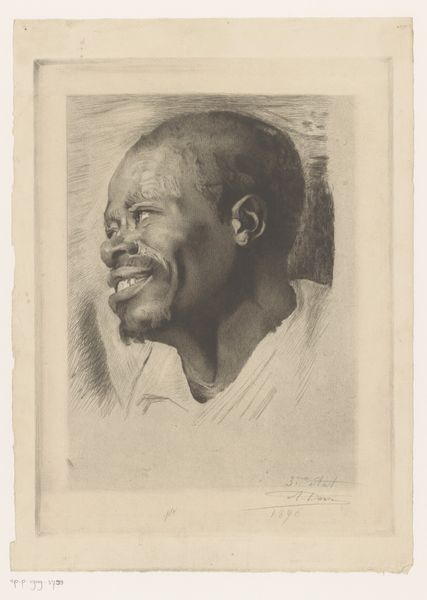

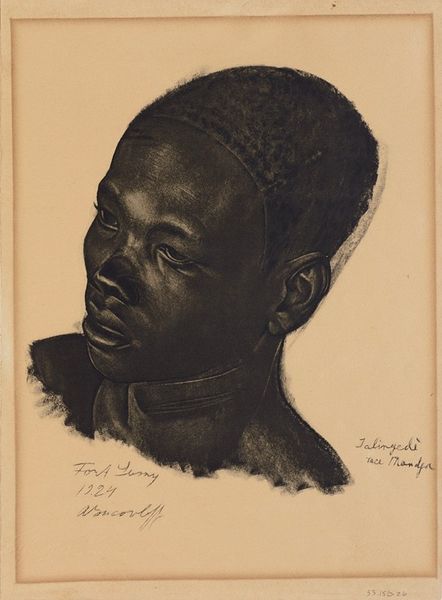

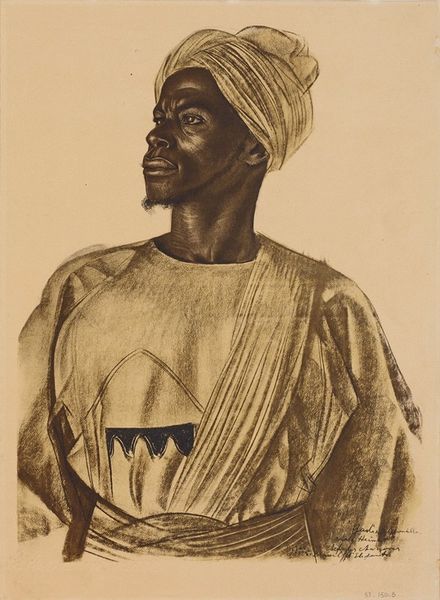

Curator: This is Wallerant Vaillant’s “Bust of a Dark Man,” a charcoal drawing dating from 1658 to 1677. It’s part of the Rijksmuseum collection. Editor: The man's expression… it's both inviting and reserved, almost secretive. And the way the charcoal renders the texture of his skin—it feels remarkably modern. Curator: Absolutely. Vaillant was a master of mezzotint, and this drawing demonstrates his talent for capturing light and shadow. Consider the way he uses the white collar to offset the darkness of his skin—a common visual trope, yet done with such sensitivity here. Editor: That contrast is striking. What I find fascinating is how little context we're given. We see the man, seemingly well-dressed, but we know nothing about his station. During this time, what narratives were being told about Black individuals in Dutch society? Curator: That's the core question, isn’t it? The Dutch Golden Age, with its burgeoning trade and colonial expansion, certainly presented complex portrayals of race and class. While some scholars interpret these portraits as demonstrations of Dutch tolerance or simply as exotic curiosities, we must consider the exploitative economic engine underlying Dutch society and representation at that time. Editor: So the symbolism, though subtle, is politically charged. Is the direct gaze an attempt to individualize the subject, to assert personhood within that system? Or, is it reinforcing a perceived power dynamic? Curator: The interpretation shifts depending on how we view Dutch colonial practices then and cultural memory now. The subject’s open expression can suggest openness, while the overall image signifies colonial tropes of power and privilege for the ruling class. The nuances of light and dark serve not just an artistic purpose but hint at socio-political undercurrents, requiring thoughtful viewing. Editor: It’s powerful how this image encourages self-reflection on social issues. Even a relatively straightforward portrait challenges the stories we tell ourselves about the past, and the power we hold now. Curator: Precisely. And perhaps through understanding the coded meanings in imagery like this, we begin to recognize the symbols influencing perceptions and actions now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.