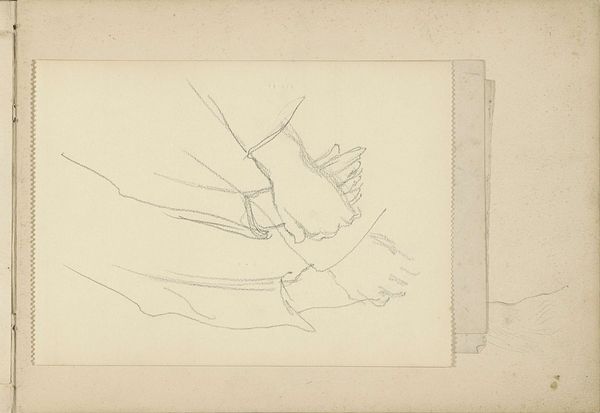

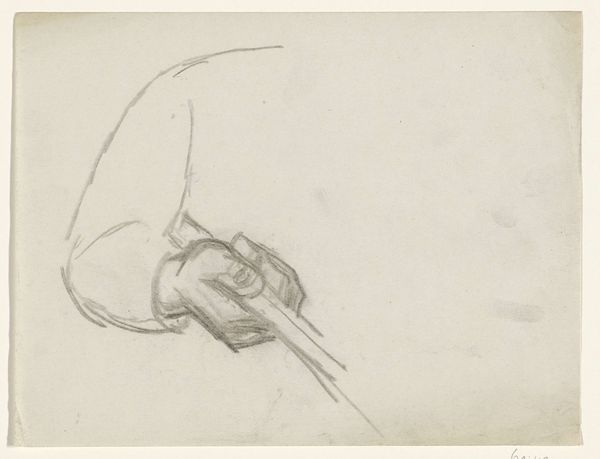

drawing, paper, pencil

#

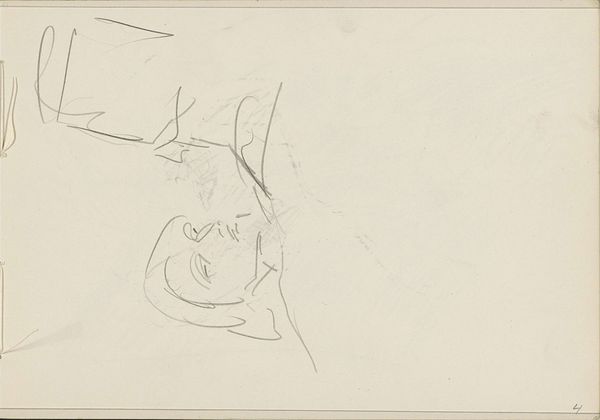

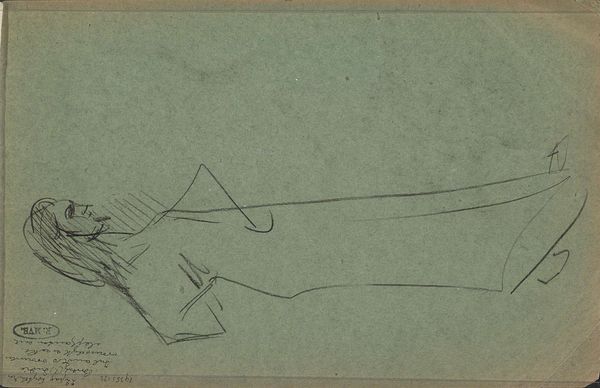

portrait

#

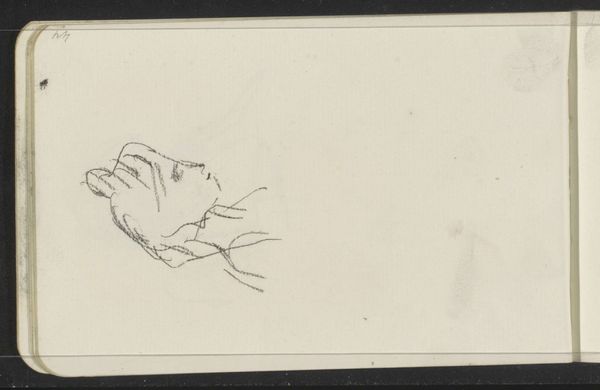

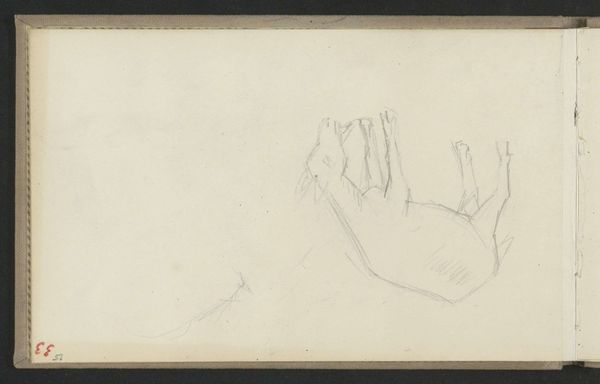

drawing

#

pen sketch

#

paper

#

form

#

pencil

#

line

#

realism

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

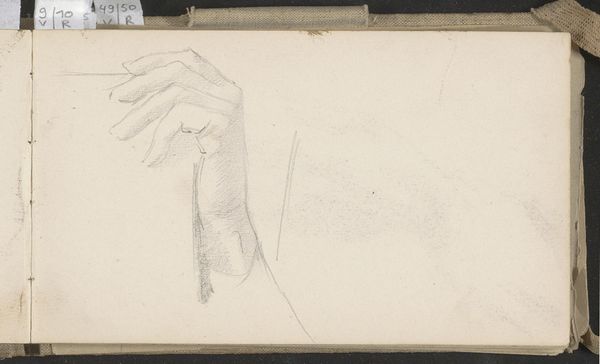

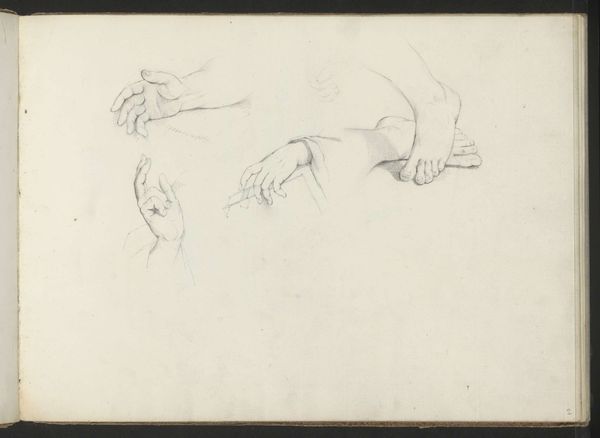

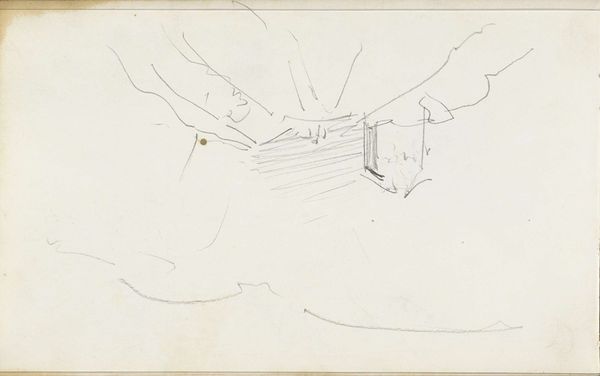

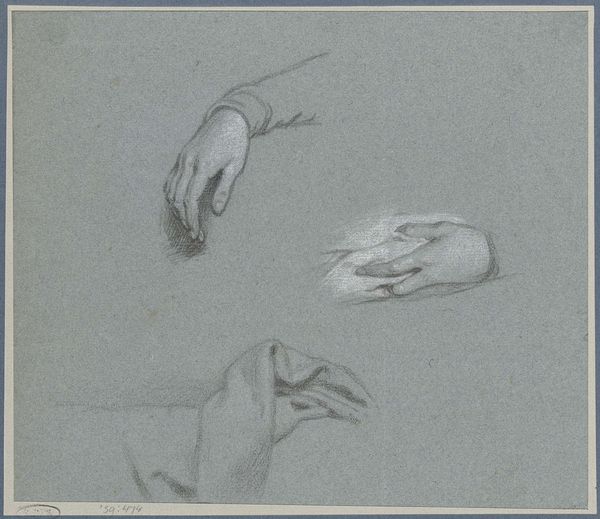

Curator: This drawing, simply titled "Handen," or "Hands," by Carel Adolph Lion Cachet, was created in 1895, employing both pencil and pen on paper. The artwork now resides here at the Rijksmuseum. What’s your initial take on it? Editor: Sparse, almost haunting in its simplicity. The lines are so delicate; it’s more suggestion than solid form. A sketch in its purest iteration. The isolation of hands as the subject also intrigues me—disembodied in this form. Curator: It's interesting to consider that isolation. Hands are often seen as tools, extensions of labor and control. But what about the lack of context surrounding them? It invites questions about the social conditions of labor at the end of the 19th century, where workers' bodies, particularly their hands, were so often used and objectified by the burgeoning industrial revolution. Do these hands reflect weariness, subservience, strength? Whose hands do we suppose that Cachet might have drawn? Editor: I see the opposite, really! Free from societal constraints and roles, these hands become studies in form. I'm immediately drawn to the negative space and the balance of light. Cachet uses line weight and direction strategically to build a composition where what isn't there is as important as what is. I would posit that these choices evoke a sense of openness, freedom, more so than fatigue. They’re graceful, even. Curator: Perhaps we can look to other works of this time to see other visual expressions of the labor movement and of bodily commodification? What sort of parallels might those present? Or, even in a theoretical sense, do you think these evoke Barthes’ “mythologies” that help to solidify a certain societal expectation for physical output? Editor: That reading feels forced given the directness of the drawing. The semiotics point, for me, inward, back to the hands as physical forms: their joints, the tension, and angle of the wrist; or perhaps outward to how the very line work captures light and texture to achieve depth with such economical gesture. Curator: I’ll meet you somewhere in the middle: perhaps there is an inherent intersectional discourse because the form invites this dialogue, particularly when understanding artistic license. It invites us to seek a fuller, more complete understanding of these hands by considering everything it seems we don’t know about them, or even about Cachet’s broader political sentiments. Editor: A reading that adds richness! For me, it remains in that quiet, almost ephemeral presence. Thanks for enriching the experience and my perspectives. Curator: Of course. That interplay is what art, at its best, invites us to undertake in all ways!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.