print, engraving

#

portrait

#

medal

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

old engraving style

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 143 mm, width 93 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

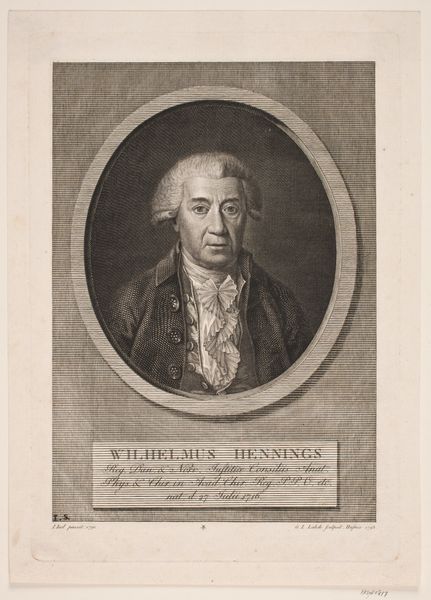

Curator: This is a portrait of Wilhelm von Rohdich, an engraving from between 1769 and 1796, attributed to Eberhard Siegfried Henne. It’s currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It has a kind of austere formality, doesn't it? The rigid pose, the tight frame. The very lines of the engraving seem sharp, almost militaristic. Curator: That rigidity absolutely speaks to its Neoclassical roots and, if we think about production, the conventions of portraiture at the time. Engravings like this weren't simply aesthetic objects. Consider the labor involved—the engraver meticulously transferring an image onto a metal plate, a physically demanding process— and how the production was dependent on specific skills, workshops and print houses. The reproduction and distribution was central to projecting power and status. Editor: Yes, absolutely. And power here is undoubtedly the theme. The inscription detailing Rohdich’s titles tells us of his high military and ministerial status, his place in the Prussian power structure. This isn't simply about memorializing a man. It’s a deliberate statement of authority and control. It intersects neatly with what we know of 18th-century militarism and statecraft. Curator: Think about how such engravings also served as tools for disseminating information and propagating a particular image of leadership. Reproducing these prints created wider access beyond the elite circles of court, also shaping public perception and reinforcing social hierarchies. They were essential commodities within a complex social and economic network. Editor: Looking at it now, I’m wondering about the colonial underpinnings. Prussia, like many European states, was benefiting directly from colonial trade. I’m curious to know how the wealth generated through exploitation financed these kinds of lavish displays and the institutions that promoted and preserved them. Was Wilhelm directly benefiting from any colonies, and where did the materials that formed the print come from? Curator: Excellent point. We see that Neoclassical art's clean, "rational" aesthetic was intertwined with complex networks of exploitation. The materiality and social conditions become inherently entangled when studying art from this period. It calls for ongoing investigation. Editor: Indeed. I mean, every aspect of the artwork, from its visual style to its creation, becomes more compelling when placed within that larger context. Curator: A fitting point. There's always more to dig into beyond the initial aesthetic impression. Editor: Agreed, it certainly gives you pause to consider it all anew.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.