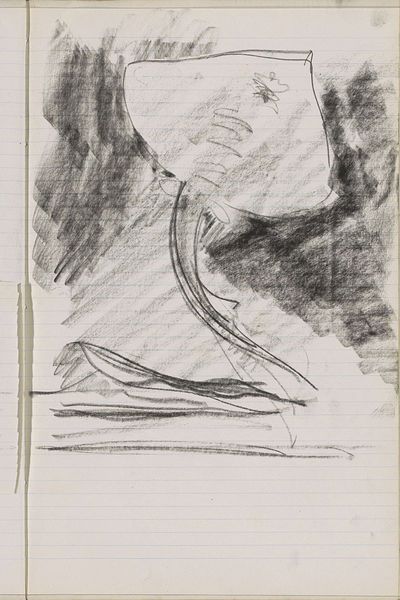

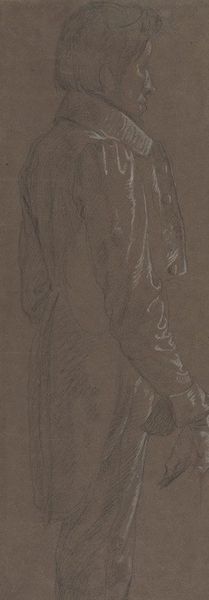

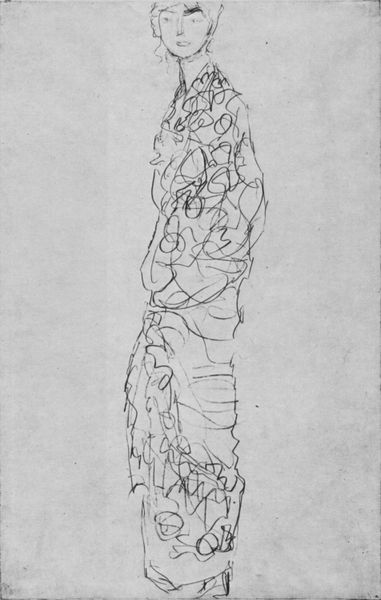

drawing, dry-media, graphite, charcoal

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

impressionism

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

dry-media

#

graphite

#

charcoal

#

monochrome

Copyright: Public domain

Curator: This drawing, “The Lady in the Hat,” was created around 1890 by Konstantin Alexeevich Korovin using graphite and charcoal. The monochrome portrait evokes a feeling of soft introspection, wouldn't you say? Editor: Introspection is one word for it. The swift, gestural strokes, that contrast of deep shadows and smudged light—they scream nervous energy, or perhaps an internalized societal anxiety bubbling up! The obscured face amplifies the feeling. Curator: Ah, the obscured face. It’s so suggestive. I see it more as Korovin reflecting the constrained roles afforded to women in late 19th century Russia. We see her through the filter of social expectation. What are we allowed to know about her? Very little, it seems. Her identity is muted, almost erased by the weight of convention, but those powerful marks could reveal an intense desire for liberation if only we had enough knowledge. Editor: Convention certainly dictates the visual language here. Look at the careful application of value—the darkest marks carve out the background, drawing our eyes to the lightest areas suggesting fabric and light on skin, using a highly readable mode of representation that would have felt instantly relatable to audiences already attuned to Impressionism’s engagement with contemporary life. But you are right. Who is she allowed to be? Is it all surface? Or is it just great expressive power of line itself? The formal elisions become paramount in understanding this piece. Curator: Exactly. This “surface,” this visible “portrait,” performs and reflects larger truths about women in that time. The deliberate ambiguity opens up interpretations far beyond a mere likeness. Think about the social and economic conditions… a middle or upper class woman, expected to be demure. Her very pose—the hands clasped—speaks volumes. It’s a portrait, yes, but it’s a portrait enmeshed in a complex web of socio-political expectation. The very materiality contributes—the chalky, fragile graphite mirroring the precariousness of her position within social structures. Editor: While your contextual interpretations offer a lens through which we could interpret those decisions, the charcoal creates depth, the graphite creates texture and value—each applied following time tested aesthetic criteria used throughout the late 1800s as impressionist styles took root internationally. This interplay, combined with the relatively standard pose that we see within other impressionistic examples… This all tells us what the drawing IS rather than simply using what the drawing SHOWS to inform broader identity debates. Curator: I find it liberating, ultimately. Korovin hands us a riddle, urging us to decode, question, and reimagine this woman beyond what’s immediately apparent on the page. It transcends mere observation. It becomes an act of historical excavation and also re-imagining potential new forms of subjectivity and visual self-expression. Editor: And I remain enthralled by how successfully Korovin leveraged light and shadow to achieve a singular effect; one that feels somehow both incomplete and totally realized. It speaks to the power of formal economy and impressionistic ideals, of allowing the visual properties speak first.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.